In the centuries since White’s death, his story has diverged in an interesting way. Generations of schoolchildren raised in the United States can probably recall reading about the “Lost Colony” at Roanoke in textbooks. In these simplified accounts, White and his fellow colonists typically figure as doomed but visionary pioneers in a larger narrative of British-American exceptionalism.

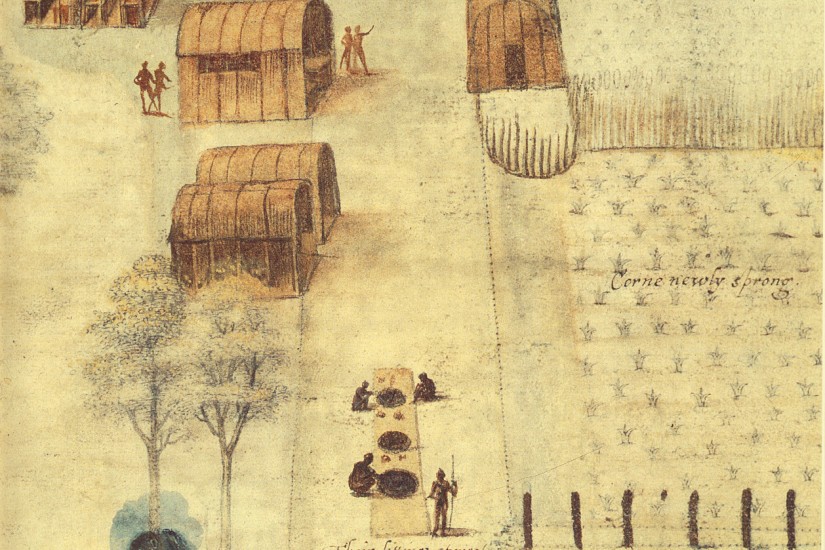

Among professional historians, White is equally famous, but for rather different reasons. In recent histories of colonial British America, it is John White the artist, rather than John White the colonial governor, who takes center stage. This is because White was a watercolor painter of extraordinary talent whose works number among the most remarkable depictions of early modern indigenous Americans ever created.

To be sure, many other European contemporaries of White offered up visual depictions of native Americans. Readers of André Thevet’s early account of Brazil Les singularitez de la France antarctique (Paris, 1557), for instance, could expect to be treated to renderings of Tupí Indians harvesting fruit, singing songs (complete with musical notation recorded by Thevet) and even munching casually on barbequed human thighs and buttocks.

Yet White’s illustrations stood out among those of his peers. Rather than working via woodblock printing or engraving, White produced paintings in vivid watercolors. This allowed him to achieve a level of lifelike detail which printed illustrations couldn’t hope to match.