“Does Harry Smith really exist?” So the writer and filmmaker Jonas Mekas began his March 18, 1965, column for The Village Voice. “For years,” Mekas wrote, Smith had been “a black and ominous legend and a source of strange rumors. Some even said that he had left this planet long ago—the last alchemist of the Western world.” This hyperbole is bizarre but unsurprising. A tireless apostle of the movement he named the New American Cinema, Mekas had devoted much of 1963 to promoting Jack Smith (no relation), whose banned Flaming Creatures became a cause célèbre, then a good deal of 1964 to extolling Andy Warhol’s switch from Pop Art to underground movies. Harry Smith was a new film genius to support, albeit a difficult one. Smith is “very brilliant, very learned,” Mekas noted in his diary, but also “crazy, evil, nasty,” and even abusive. “I don’t know how I managed to make him show his films.”

Harry Everett Smith, who died at age sixty-eight in 1991, has officially arrived. His centennial was marked by two firsts: the publication of the first biography on him, John Szwed’s Cosmic Scholar, was complemented by “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten,” a half-floor exhibition of films, paintings, and artifacts at the Whitney Museum, the first major museum show devoted to his work. The title, a phrase sometimes used by Smith, comes from a book on gnostic texts by the British theosophist G.R.S. Mead.

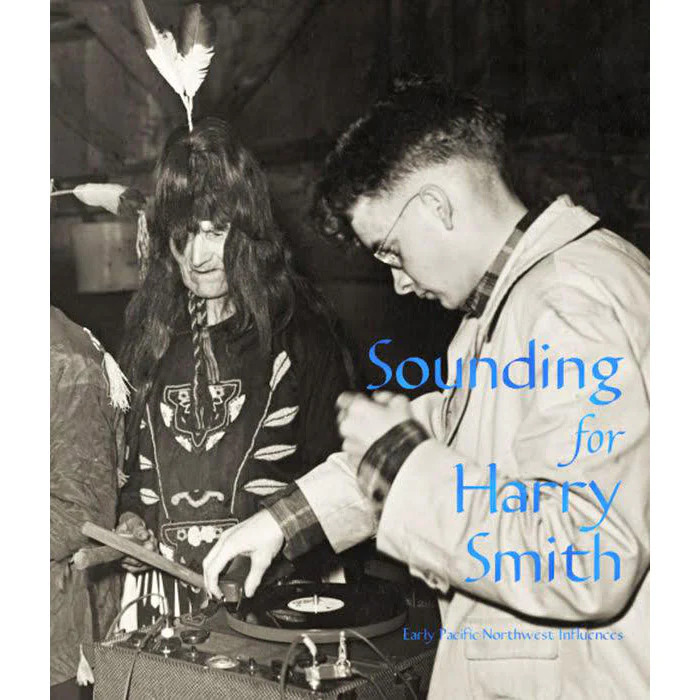

At once famous and obscure, marginal and central, Smith anticipated and even invented important elements of the Sixties counterculture, most obviously with his idiosyncratic six-LP Anthology of American Folk Music, issued by Folkways Records in 1952, which provided a basis for the folk music revival of the early 1960s. Less known are the homemade light shows Smith contrived circa 1950 for a San Francisco jazz club. More general inspiration may be found in his abiding interest in Native Americans, arcane spiritual knowledge, and fondness for hallucinogenic drugs. The headline for the New York Times art critic Holland Cotter’s review of the Whitney show identified Smith as a “shaman,” and Szwed describes the tiny basement apartment in the Bronx where Smith lived in the early 1950s as something like the original hippie crash pad—“an atelier with DayGlo paint and black lights, ‘alchemical’ substances bubbling on the stove.”