Tracing genealogies has become immensely popular of late, and numerous companies offer to help you search through historical records or analyze your DNA. The pastime is no doubt enlivened by the scintillating possibility that you might discover noble blood, or even a notorious rogue, hiding in your family tree. But such discoveries generally don’t tell the searcher much; most of us have little idea of how our genes are bequeathed to us at all.

Carl Zimmer’s interest in genetic inheritance began when his wife, Grace, was pregnant with their first child, and the couple met with a genetics counselor. Zimmer, who has written books on evolution, neuroscience, and bacteriology, didn’t see the point of the meeting, for they had already decided to have the child regardless of any genetic flaws that might be found. It was only when the counselor asked the couple about their family histories that Zimmer realized how little he knew about his own, and began to be curious about his ancestry.

The result, many years later, is both two delightful, healthy daughters and She Has Her Mother’s Laugh, a grand and sprawling book that investigates all aspects of inheritance, from ancient Roman law to childhood learning, and on to the bacteria that inhabit our belly buttons (which are surprisingly varied among individuals). Along the way, the book provides many amusing historical anecdotes and important scientific insights.

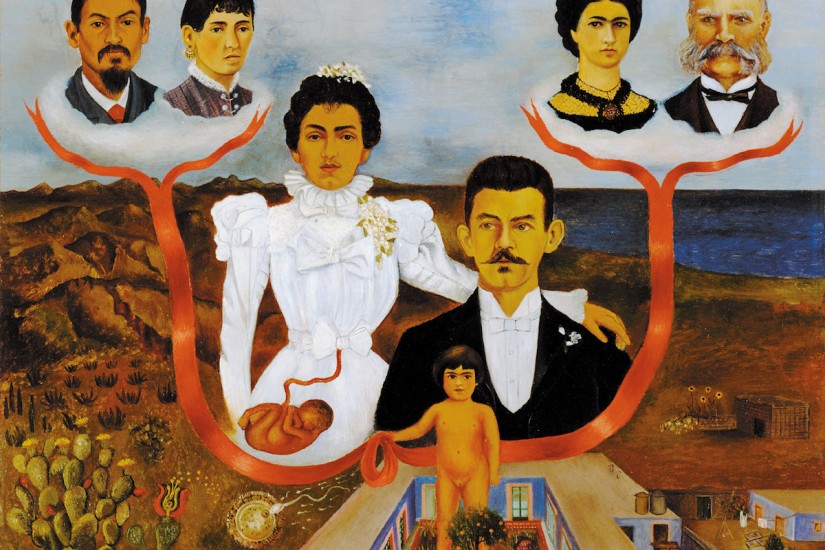

Inheritance, as a means of endowing privilege, has been of vital importance to people ever since the Neolithic period some ten thousand years ago. Pedigrees (from pé de grue, the foot of a crane, which resembles the connecting lines on ancestral trees) have long been used to justify social hierarchies. In times past, the European nobility would spend lavishly to draw up impressive (and often invented) pedigrees for themselves.

In 1715 the Irish noble Viscount Mountcashel published a pedigree in which he claimed to be able to trace his ancestry all the way back to Adam and Eve. In Mountcashel’s time, the popular understanding of heredity didn’t extend much beyond the theory that men planted seeds in the wombs of women, where they were nurtured. Yet it does seem odd for Mountcashel to have averred that, in all the ages since Adam, not one of his female ancestors had ever become pregnant by anyone but her wedded partner.