The 1610s were a key decade in tobacco’s transformation into a new global obsession. Before long, the gift (or curse) of smoking had given rise to one of the world’s most lucrative industries, emerged as a key driver of the Atlantic slave trade, and initiated a global bad habit that humanity still hasn’t kicked more than four hundred years later.

But smoking was about more than just tobacco pipes in the early modern period; the enormous pipe god of Bacon’s dance performance was part of a more complicated, and far stranger, panorama of smoking technologies and practices. The story of smoking in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is capacious enough to include the distillation apparatus of the alchemist, the water pipe of the cannabis smoker, and even medicinal smoke enemas.

This diversity is not what we would expect from the standard history of smoking, which goes something like this.

Before 1492 smoking was widespread among the tobacco-loving peoples of the Americas but unknown across the Atlantic. Then Christopher Columbus witnessed Taíno men in Cuba puffing on “certain herbs...by which they become benumbed and almost drunk” and, upon further investigation, learned that “they call this tabaco” (this, at least, is what Bartolomé de Las Casas claimed Columbus had recorded in his now-lost journal of his 1492 voyage). By the 1560s a growing number of Spanish authorities began advocating that Europeans take up the practice—particularly the Seville physician Nicolás Monardes, who hailed smoking as a “miraculous” cure for over twenty diseases. And by century’s end tobacco was being grown domestically in areas stretching from Spain to Turkey to Gujarat. Meanwhile, tobacco plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil were emerging as hubs of the Atlantic slave trade. All were in the service of an enormous growth in consumer demand for tobacco that stretched beyond Europe and into Asia and Africa.

The English followed the Spanish example, led by the polymath Thomas Harriot, author of A Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1588). Harriott, echoing Monardes’ almost monomaniacal devotion to the drug, praised tobacco for its purported ability to open “all the pores and passages of the body” and cure “many grievous diseases.” Within a few decades, even James I was unable to suppress the drug; his passionate Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604) is remembered as one of history’s most abject drug-policy failures. A decade later, tobacco had become both abundant and cheap throughout Europe, while Harriot lay dying of a painful cancer of the nose that was probably linked to his continued addiction to what James had presciently called a “canker or venime,” or venom.

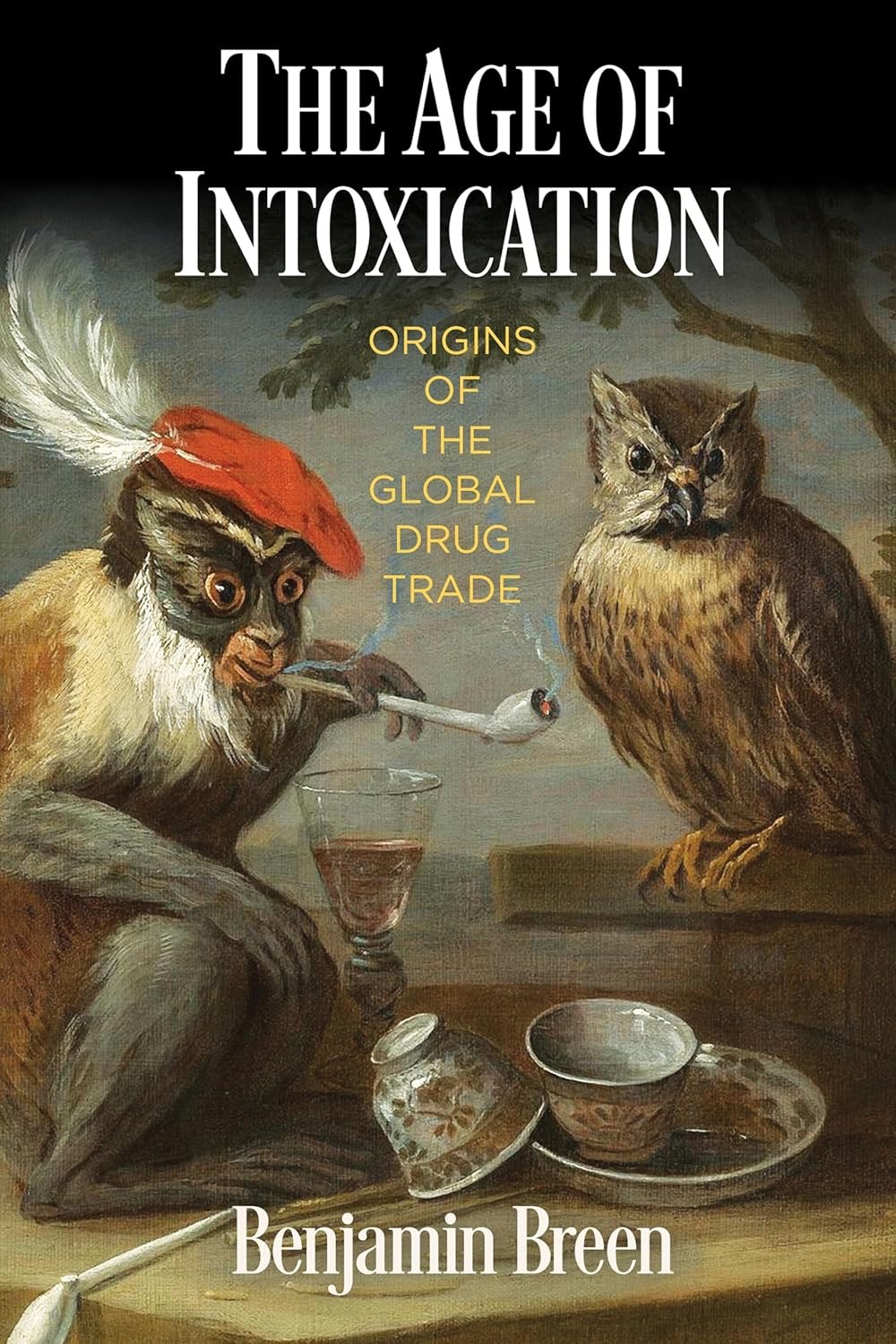

By the 1650s the tobacco pipe was perhaps the most widespread emblem of globalization and European empire. Smoking had gone global.

Versions of this account of the globalization of smoking have been told countless times. Broadly speaking, they’re true. But they can also be misleading.

Tobacco is indeed native to the Americas, and early modern Europeans, Africans, and Asians did encounter tobacco smoking as a new practice without precedent in ancient texts or preexisting social conventions. But, as archaeologists and anthropologists have been documenting for decades, tobacco was not the only drug that the peoples of the Old World smoked—even before the voyages of Columbus.