On December 8, 1971, a Presbyterian pastor in Greenville, SC counseled three women on their “problem pregnancies,” ultimately connecting them with clinical abortion providers. The first woman was a white, 21-year-old university student. Her relationship with her boyfriend had ended that October, and she believed abortion was, to use her words, a “last ditch contraception.” The pastor referred her to Women’s Services in New York, which was one of the clinics that opened when the NY state legislature legalized abortion in 1970.1 In cases like this, South Carolina pastors scheduled appointments, arranged transportation, and even secured funding for women to travel to New York for regulated, legal procedures. When inter-state travel was not an option, pastors would connect women with licensed medical doctors within South Carolina for clandestine abortions.

The second patron was a 23-year-old divorced white woman who already had a three-year-old son. She was trying to reconcile her marriage and wanted to have more children, but was having intercourse with another man and feared the repercussions of either partner learning of her pregnancy. The pastor arranged transportation and scheduled an appointment for her in New York.2

The third woman the pastor saw that day was an 11-year-old African American girl whose father believed she was “coerced” into intercourse by an 18-year-old boy. The pastor determined that the girl and her family were “too hysterical for New York,” and scheduled an abortion with someone named “Dickson” at the local Greenville General Hospital.3

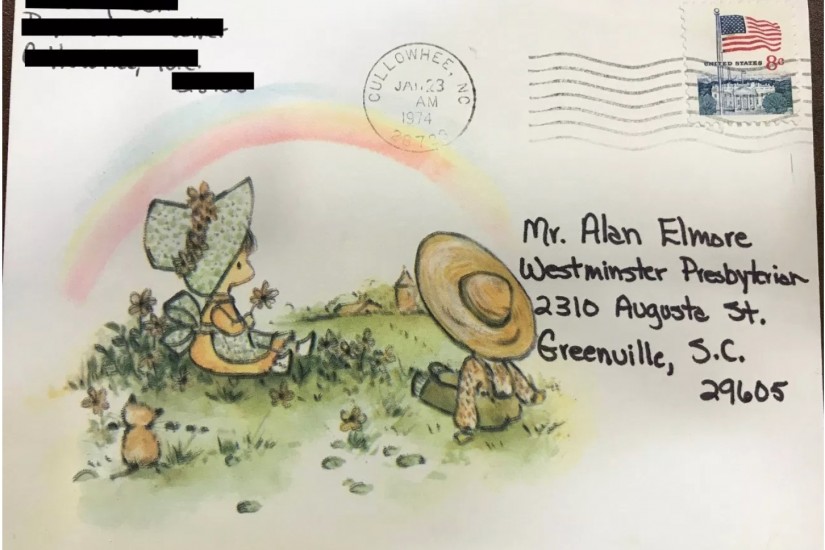

Days like December 8th, 1971 were common for pastors working for an organization called the South Carolina Clergy Consultation Service for Problem Pregnancies (SCCCS). In the years leading to Roe v. Wade (1973), this group of multi-denominational clergymen were active in helping women in South Carolina navigate and procure abortion services. We know this from archival files of SCCCS clergy case notes, called “Questionnaires” for “problem pregnancies,” now housed at Winthrop University Louise Pettus Archives.

The SCCCS records serve as a reminder that illegality, even in politically conservative “bible belt” states such as South Carolina, did not prevent women of diverse backgrounds from seeking pregnancy terminations. These records demonstrate, moreover, that anti-abortion sentiments and religiosity have not been mutually exclusive in the recent past, as many contemporary pro-life campaigns would suggest. Pastors in the SCCCS believed it was their “moral obligation” to counsel women with “problem pregnancies,” and to provide viable, alternative options to “back alley” abortions.