[Editor’s Note: Over the course of 2022 and 2023, New American History Executive Director Ed Ayers is visiting places where significant history happened, and exploring what has happened to that history since. He is focusing on the decades between 1800 and 1860, filing dispatches about the stories being told at sites both famous and forgotten. This is the 19th installment in the series.]

The computer game Oregon Trail, introduced in 1971, has migrated over the decades from blocky text and floppy disks to fluid graphics on platforms of all descriptions. Our kids played it back in the 90s.

As Abby and I prepared to head west in our RV, aka Bertha, following the actual Oregon Trail for a good stretch, we joked about the various pitfalls that we remembered from the game. We wondered how much we could carry without breaking an axle during a river crossing, or contracting dysentery at some out-of-the-way campground.

As it turns out, the joke was on us. The night before we were to leave, we ran square up against another challenge from the game: the need to preserve food.

We had carefully prepared for the longest leg of our journey, purchasing small items to make for a more pleasant month on the road. We had carefully inflated the six tires, checked all the fluids, and even cleaned the windshield to be ready to pull out early in the morning.

The afternoon before our planned departure, I plugged Bertha into an outlet in our garage to chill the freezer overnight. A blue light flickered on the refrigerator’s panel and then went out. I dug out the owner’s manual and followed the steps to troubleshoot electrical problems, checking every circuit breaker and fuse. Nothing worked. I called roadside assistance, which connected me, ironically, with a technician in Oregon. We talked through the problem and I texted him a photo of the equipment behind an exterior panel. He told me I had done what I could and that I would have to take Bertha in for service. It looked like the control board–a complex electronic assemblage–had failed.

Our hearts sank. We would now lose days on our trip. It was a holiday, so we had to wait until things opened the next day. I tried visiting a nearby dealer that sold RVs with the same refrigerators as ours. They didn’t have the part in stock. The following day, our dealer worked us into a busy schedule. Hours went by. Finally, my service liaison came out to confirm the control board diagnosis, but could not locate a part to fix it. Despite the Nordic-sounding name of our refrigerator and its manufacturer’s headquarters in Ohio, the refrigerator had been manufactured in China.

We found ourselves in a situation familiar to players of Oregon Trail. Without refrigeration, our food supplies would not sustain us for the journey. Abby had frozen simple meals to heat each evening after we had set up camp, but we had not salted any pork and could not drive cows to milk or slaughter along the way, Our vehicle, not unlike the creaky wooden Conestoga wagons on the actual trail, had only a limited space — in our case, an eight-cubic-foot refrigerator. That heavy stainless steel box, occupying valuable space in the middle of our camper, now risked becoming an expensive cabinet.

We knew that we would not actually go hungry, but we also knew that living off highway food carried longer-term dangers, especially for septuagenarians. We might not contract dysentery, but we would certainly submit ourselves to elevated cholesterol, unsaturated fats, and sodium. We needed refrigeration.

Turning to the strategies of the Oregon Trail game, we weighed options and tradeoffs. We spent resources on an electric cooler. Though it held only a third of the refrigerator’s capacity, it would be better than nothing. We determined that we could, just barely, wedge it into space occupied by one of the bench seats at the table.

Just as we were preparing to pull out with our reduced refrigeration capacity, the story took another twist. Our RV dealer was somehow able to locate a new refrigerator and have it shipped to Richmond. After three more days of delays, it was finally installed. We returned the electric cooler, loaded the clothes and food stacked in the house for days, and cleaned the windshield again.

We had lost more than a week in trying to procure a small electronic part — the equivalent of a harness ring or axle grease in the Oregon Trail game. But we did not worry that the delay would increase the odds of freezing to death from a freak snowstorm in some Rocky Mountain pass. Our inconvenience, in a world filled with expectations of instant consumer gratification, was a faint reminder of the challenges confronting families who crossed the continent when the Oregon Trail was anything but a game.

I’m writing this early on a Sunday morning in a nearly deserted RV campground in Fort Laramie, Wyoming. It is the end of the season for the campground, its owners told us, and we understand why: the temperature fell to 40 degrees last night. The air is clear and in constant motion, the wind a perpetual presence. Coal trains passed through town — and, it felt, our campsite — until after 1 o’clock this morning, their horns piercing the night and whatever sleep we had managed to muster since the last train.

Fort Laramie is a fitting place to pause on our trip after days of following the Oregon, California, and Mormon Trails across Nebraska. The first sign a visitor sees posted at the historic site announces that you are standing at what was “perhaps the single most important location in America’s expansion into the west.” Several places could vie for that distinction, perhaps, but the histories of Native peoples, the fur trade, the U.S. Army, and the migrations of white settlers did indeed converge and conflict at Fort Laramie.

Abby and I have traveled throughout the West with our kids and lived in California for a year, and I have studied 19th-century America for a long time. Still, it’s hard to lose the eastern habit of imagining the nation’s history as moving from east to west. The language of “expansion,” not to mention “the frontier” or “manifest destiny,” obscures the experience of people who already lived in what became known as “the West.”

We glimpsed that vast history at the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas. Remarkably, only four percent of the 170 million acres of prairie that covered much of North America, from Canada to Texas, still exists. The rest was long ago plowed into fields, towns, and roads. The Preserve exists because the Flint Hills of central Kansas and Oklahoma proved impervious to plows.

The tallgrass prairie is deceptively complex. More than 500 species of plants thrive in the prairie, providing refuge for hundreds of varieties of birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals. The park historian admitted that many visitors are disappointed that the prairie is not more dramatic, even when flowers are blooming in the spring, nestled in the grass. We visited in the fall, when the tall grass is usually at its tallest — six feet or more — but it has been a dry year and we could see over the tallest foliage.

For generations, people from the East mistook the prairies’ rich subtlety for barrenness. Hundreds of thousands of settlers passed through the prairies, at great cost and risk, to get to the lush valleys of Oregon, the sanctuary of the Great Salt Lake, or the goldfields of California. Much of the settlement of the Plains, as a result, took place after the settlement of the Pacific.

The first practical trail across the Rockies was forged from the Pacific coast by fur traders. Connecting trails carved by animals and Native peoples, traders of British, French, and American backgrounds mapped that trail in 1812. Their efforts were driven by the trade in beaver hides, all the rage in the cities of the American East and in Europe.

The networks of trade were extensive and regular. Traders met Native hunters and supply wagons from St. Louis at an annual rendezvous in the territories that became Wyoming and Utah in the 1820s and 1830s. Christian missionaries, including women, traveled overland into Oregon with fur traders in 1836 to convert American Indians, joining missionaries who had settled in Oregon from the Pacific.

As relentless hunting exhausted the population of beaver, a trade in buffalo hides grew rapidly. In the 1830s at what became Fort Laramie, two men built a trading post where the Lakota brought tanned buffalo hides to exchange for manufactured goods. A booming trade commenced.

All of this happened before the Oregon Trail, as it is commemorated, began. That story began when a white family, including children and an expectant mother, made the journey from the east in 1840. John C. Frémont published an immensely popular guide to the trail in 1842, building on notes and maps he and a small expedition gathered and turned into a stirring narrative with the help of his teenage wife, Jessie. It detailed landmarks, water sources, and camping sites along the way, and reassured those considering the trip that the South Pass was no steeper than city streets back east.

Three vast migrations in the 1840s and 1850s followed the same trails over much of what is now Nebraska: to Oregon, to the Great Salt Lake, and to the goldfields of California. Together, more than 300,000 people trekked across the prairies. Conveniently enough for us, the trail followed the same path as Interstate 80, so that the landmarks of the 19th-century journey align with those a traveler finds today.

We had begun our own retracing of the overland trails days earlier, far to the east, at Fort Kearny, built in 1848 to aid travelers on the Oregon Trail. This fort was created not as a military outpost, but rather as a supply station and post office. To early settlers, material aid was more valued than military protection, as the Native people they encountered along their journey turned out to be aids, allies, and trading partners rather than threats.

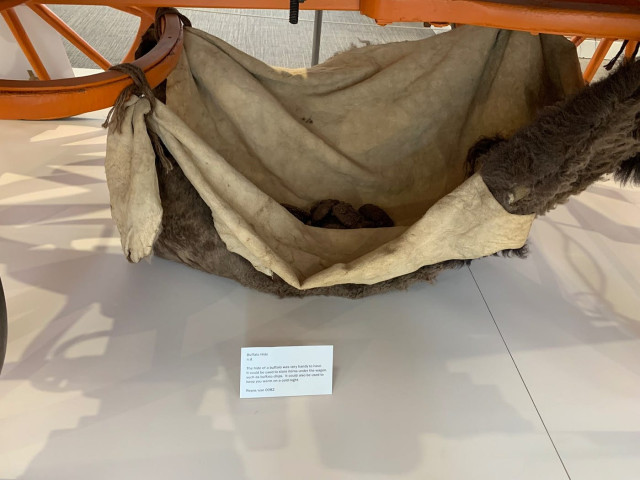

Two large museums devoted to the settlers’ journey helped us understand how thousands of families managed to survive the great dangers of the trail: disease, accident, and exhaustion. The Stuhr Museum in Grand Island is a gleaming modernistic building constructed in the 1960s to display contemporary art, historic artifacts, and a reconstructed railroad town from the 1890s. A particularly illuminating exhibit in that museum depicted a buffalo hide hanging beneath a wagon of the sort travelers used. That hide held the supply of buffalo chips — dried dung — that provided fuel for the travelers. Children would help fill the suspended hide for cooking and warmth during the journey. I had wondered how they passed the time…

A bit farther west on I-80, we came upon an astonishing museum built across the highway: The Archway. The impressive structure, first imagined by a Nebraska governor in the early 1960s to celebrate the “American Spirit of Adventure,” was endorsed by others and finally completed in 2000. Its 1,500-tons, spanning the Interstate like a covered bridge, contains a giant diorama occupied by life-sized figures.

Visitors walk among scenes from the trail along the Platte River, including a thunderous storm on the prairie and a thundering herd of buffalo. The museum invites visitors to “imagine the daring and determination of the people who first traveled the Oregon Trail, the high-spirited adventure of racing to California during the Gold Rush of 1849, the devotion of the Mormons who moved west in search of religious freedom.”

The Archway dramatizes the physical travails of the overland trails. One scene depicts a wagon crushed by the weight of beloved objects too heavy to cross the continent, abandoned along the way. In the background, a family mourns the child they had to bury in a lonely and rocky spot.

As powerful as the Archway exhibits were, we knew that the actual landscape of the overland trails lay before us. Having glimpsed some of the hardships the settlers endured, we had a greater appreciation for the beauty of Ash Hollow, where water, trees, and shade welcomed people who had rattled for weeks over open prairies. We understood the excitement of travelers who first saw Chimney Rock, the landmark on the trails most often noted in the journals and diaries kept by many migrants.

At Scotts Bluff, we walked a section of the trail where wagons and oxen lined up before proceeding through a narrow pass between towering masses of stone that travelers imagined as ancient castles. Models of the oxen teams, which in the busy season for the trail would have been lined up for miles, allowed us to imagine the immense amounts of grass such large animals consumed along the way.

Finally, we arrived at Fort Laramie, a place, as its sign declared, that saw all the stages of the fur trade, mass migrations, and negotiations with Native peoples that took place in what is now eastern Wyoming in the decades between 1820 and 1860. It looked nothing like the western forts we remembered from the ubiquitous Western movies and TV shows of our youth. Like Fort Kearny, farther to the east, Fort Laramie was an assemblage of buildings largely devoted to aiding the travelers who came through. Its most important buildings were a post office and trading post, where migrants could get supplies and write to people back home to let them know that they had made it this far on their journey.

The National Park Service told the story with heartening honesty. By the 1850s, exhibits admitted,

“[t]ens of thousands of people choked the dusty trails with masses of bawling farm and draft animals. Destruction followed in their wake. As thousands of wagons passed over the trails, game was killed and driven off, depriving the Indians of subsistence. Emigrants’ livestock destroyed the grass for several miles in all directions. The trail corridor scarred the land, and remains visible over one hundred and fifty years after its carving.”

Relations between the United States and the American Indians deteriorated, and the meeting that produced the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 was the largest known gathering of Northern Plains tribes in history. More than 10,000 people from virtually all of the plains Indian nations gathered at Horse Creek to make peace with the whites and end intertribal warfare. The pledges of peace soon broke, however, and, as the National Park Service exhibits explained, “by the late 1850s, waning emigration and rising tensions with the Indians had changed Fort Laramie’s role from a rest stop for travelers to a base of military operations against the Northern Plains tribes.” That is when the history so often depicted on film and TV screens occurred, the history many people from around the world now travel so far to witness for themselves.

The Overland Trails, important as they were, traced narrow paths. We knew the West had many other stories to tell.