What historical treasures could be in your attic?

When C.P. “Kitty” Weaver sat down to write a biography of her great-uncle Samuel Tappan, she discovered in his personal papers a handwritten copy of the U.S.-Navajo Treaty, which was negotiated and signed in New Mexico 150 years ago this June. A member of the 1867-68 Peace Commission tasked with meeting and signing treaties with Native Americans across the Plains and Southwest, Tappan was one of two federal representatives to meet with Navajo leaders.

It made sense to Weaver that Tappan would have a copy of the treaty. But only recently did she learn that archivists, Navajo historians and journalists had been searching for this document, one of three original copies, for quite some time. Called by the Navajos Naal Tsoos Saní (the Old Paper), it is one of the most important documents produced in the 19th century, both for what it reveals about the Navajos and about the role of the West — and the subjugation of its indigenous people — in the Civil War.

The high deserts of the Southwest are frequently overlooked in Civil War history. While the North and South fought each other, they also turned to the West to help them win the war. The gold buried in its mountains could buy food, arms and clothing for their soldiers, and they could transport all of these supplies in and out of Pacific ports. The West was also central to both Union and Confederate visions of the future. Northerners imagined that its millions of acres could be taken up by free laboring farmers, while Southerners saw the region as a potential epicenter of an empire of slavery.

Neither anticipated the resistance they would face from Apaches and Navajos, who saw the white man’s war as an opportunity to raid wagon trains and camps, increase their horse and sheep herds and maintain their control of the Southwest.

Tappan was embroiled in this Western theater of the war. He had left Massachusetts in 1854 to help establish free-soil settlements in Kansas, and from there he joined the rush of gold seekers to the Rocky Mountains in 1859. When Confederate Texans invaded New Mexico in the fall of 1861, Tappan joined the Union Army in Colorado and marched south to fight the Confederates at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in March 1862. It was a decisive victory: The Texans retreated, and their dreams of winning the West were dashed.

In the fall of 1862, Tappan returned to Colorado with his regiment just as the Union Army turned to fight New Mexico’s Native Americans. Brig. Gen. James Carleton decided to initiate these campaigns for two reasons. First, he had 2,000 soldiers at his disposal, the largest fighting force ever assembled in the region. Second, to fully control the Southwest’s mineral resources and transportation corridors, Union soldiers would have to take them from the Apaches and Navajos.

Carleton’s campaigns were part of a shift in the federal government’s stance toward Native Americans in the mid-19th century. While in the early years of the United States, the government relied on treaty-making to acquire lands and establish peaceful relations with tribes, President Andrew Jackson shifted to a combination of warfare and treaties to ensure the removal of Native Americans from their eastern homelands to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In 1862-63, Carleton made clear to his soldiers that the Union Army’s campaign would not end in a treaty of peace, but in Apache and Navajo surrender and incarceration to allow for the Union’s manifest destiny in the West.

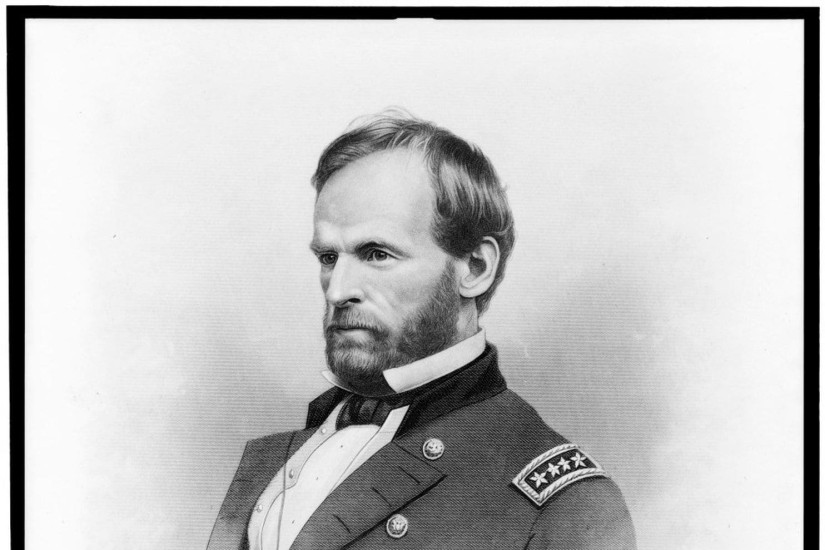

To force Apaches and Navajos to capitulate, the Union Army destroyed their fields, herds and homes. These “hard war” tactics were not yet common in the Civil War; Union soldiers under Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman would initiate his scorched-earth campaign a year later in Georgia and South Carolina.

These strategies were successful in New Mexico; a small group of Mescalero Apaches and more than 8,000 Navajos surrendered to the Union Army. In a series of “Long Walks” between 1864 and 1866, the Navajos traveled more than 300 miles from the tablelands of northeastern Arizona to the Bosque Redondo reservation in the New Mexico territory.

At the reservation, which Navajos also called Hwéeldi (Land of Suffering), they endured four years of incarceration in an environment that could not sustain them. The water of the Pecos was alkaline, and there was barely enough wood in the area to feed their fires for a month. A series of natural disasters, including insect infestations, hailstorms and drenching rain, ruined the corn they tried to plant. Without enough rations from the Union Army, captives were constantly hungry and many died of starvation.

For several years after the establishment of Bosque Redondo, officials visited the reservation, asking Navajos and Apaches questions about their living conditions. The federal government, focused on paying war debts, was concerned about how much the reservation cost. They were also unsure about whether the Army or the Indian Bureau should control Bosque Redondo.

Every time government agents arrived, the “captive Indians” told these men how they were starving and suffering. But nothing happened. By 1868, the Navajos at Bosque Redondo had answered enough questions. Now they wanted to negotiate with delegates from the U.S. government.

On May 27, two members of the peace commission arrived: Tappan and Sherman. After three days of councils with the Navajo headmen, Tappan and Sherman agreed to send the Navajos back to their homeland, give them 15,000 sheep and goats and 500 beef cattle, and provide material goods for 10 years. The Navajos consented to live within their new reservation boundaries; cease raiding New Mexican and other Native American communities; allow forts, an Indian agency and a railroad on their lands; and send their children to English-speaking schools.

For the Navajos at Bosque Redondo, the moment was bittersweet. On the one hand, they had successfully persuaded the U.S. government to give them what they wanted, and the treaty itself recognized their sovereignty. It was a moment that represented their strength and perseverance as a people. On the other hand, as Navajo historian Jennifer Nez Denetdale has noted, it was “the point at which the Navajo people lost their freedom and autonomy, and came under American colonial rule.”

Three copies of the U.S.-Navajo Treaty, signed June 1, 1868, recorded this agreement. Tappan and Sherman gave one copy to Barboncito, a headman who had spoken on behalf of all of the Navajos; this copy has since disappeared. A courier took one copy back to Washington, D.C., to submit to Congress; this copy was preserved at the National Archives.

Tappan took his copy of the treaty, tied with a red ribbon, from Bosque Redondo to Santa Fe, then on to Denver City and east to the nation’s capital. His copy was meant to be filed with the records of the peace commission. Kitty Weaver does not know why Tappan kept it, but she thinks he probably placed it with other personal papers in the attic of the family home in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Mass, when he returned there in July 1868. It was passed down to Weaver in 1975.

The treaty, however, is not just a family heirloom. It is one of the most significant documents produced in the 19th century, evidence of the importance of the West in waging the Civil War and the war’s role in shaping federal Indian policy. The treaty also reveals the resilience of the Navajos, who used the negotiations to secure a measure of freedom for themselves. And in this digital age, it reminds us how brittle pieces of paper, scrawled over with ink, are central to understanding our past.

Last month, a representative from the National Archives authenticated the Tappan copy, and Weaver took it to the New England Document Conservation Center. The text conservators there are repairing some tears and preparing the pages for another journey. In June, Weaver will carefully pack up Tappan’s treaty and deliver it to Bosque Redondo for the 150th anniversary commemoration events. In addition to watching tribal dances and other ceremonial activities, attendees will be able to view the treaty in a special space at the Bosque Redondo Memorial museum.

The Tappan copy of the U.S.-Navajo Treaty has traveled many roads over 150 years, and its survival — like the Navajos’ persistence — is inspiring. It is also a material reminder of the ways that treaties have made history and shaped collective memory, and of how some parts of the past that we think are lost reemerge, suddenly, into the light.