I read and reread every available source for descriptions that might be valuable and rediscovered lost sources—ones researchers, historians, and librarians had used in pursuit of other topics, but not to analyze early American music. Along the way, I became frustrated that white supremacy has distorted this history and that better sources don’t exist. I used these sources to understand the context in which the banjo was played and tried to interrogate the bias of writers and observers by learning more about them and the world they lived in. I also looked at my own bias as a Swedish American white woman trying to understand a culture that isn’t my own but is integral to American culture.

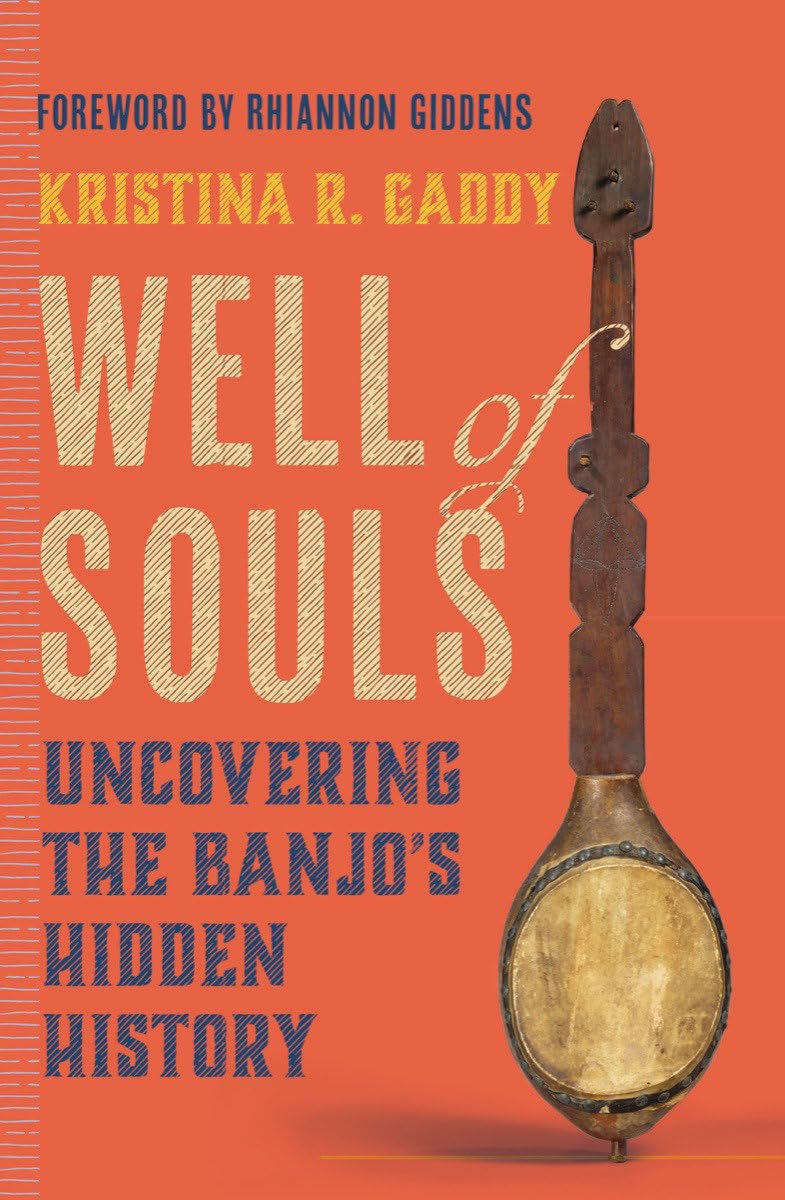

During my research, I saw the same cultural elements appear in images of the banjo, descriptions of the banjo, and the three existing early instruments. As archeological evidence of the banjo’s beginnings is scant, these elements became stand-in artifacts: evidence of behavior, movement, and relationships. The banjo appears in Suriname and New York and everywhere in between. What does that geographic spread say about the culture and lived experience of the people of African descent who created, played, and listened to the banjo? Is it really an American instrument, as we commonly think of it today?

Our biases have limited the banjo to being a secular instrument: it is in the hands of a lone white man on a porch, a backup instrument in a bluegrass band, or a driver of melodies for a square dance or clogging routine. The stereotypes of the instrument from the last 180 years create these images in our minds. The assumption is that the banjo must have always been a secular instrument—from the Latin word saeculum, meaning of the present world. This is putting a Eurocentric worldview on an instrument born of African beliefs and traditions.

From my research, I realized that the banjo once served a higher purpose. The instrument was sacred—a word derived from the Hittite šakla‐i, meaning custom or rites, something of an otherworldly realm, of spirits, ancestors, and worship. The banjo was not just a musical instrument but a spiritual device, and it fit into a cultural complex of music, dance, and spirituality. In the 1970s, when scholars of the African diaspora still had to argue that the enslaved who arrived in the Americas had not been denuded of their culture, poet and scholar Edward Kamau Brathwaite wrote, “There is no separation between religion and philosophy, religion and society, religion and art. Religion is the form or kernel or core of the [African] culture.” He warned that when religion is mentioned, a full cultural complex should be considered. I hope to reveal that cultural complex and to have the banjo take us on a journey to remember the hidden, the willfully ignored, the forgotten, and the lost.