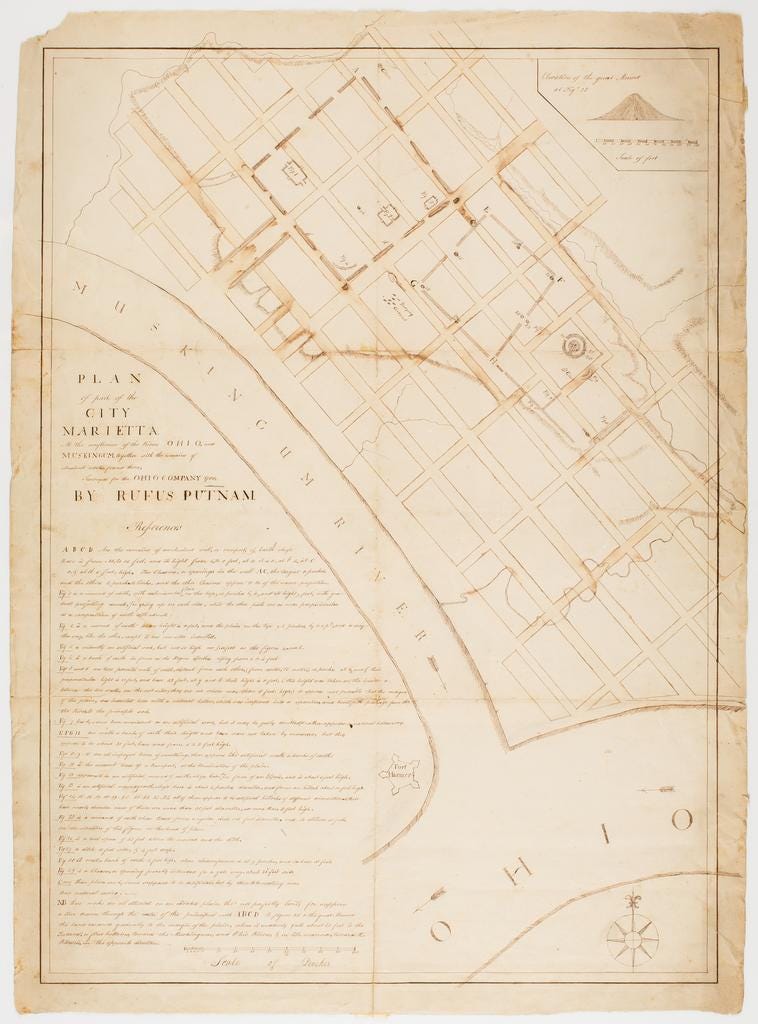

In 1788, members of the Ohio Company of Associates arrived on the western shores of the Ohio River to build the first U. S. city in the Northwest Territory. Led by Revolutionary War veteran Rufus Putnam, these New England men determined to build the city of Marietta around a complex of geometric earthworks. Today, we recognize that Algonquian peoples built these structures as sites of ritual between 100 BCE and 500 CE. In 1788, however, Putnam and his associates labeled them American antiquities.

When Putnam plotted city squares around the largest earthworks to preserve them as “monument[s] of antiquity,” he shaped history to gain control of land. Residents of the early United States were fascinated with ancient Rome and sought to fashion their new nation as a modern, American version of a classical republic. Marietta founders used preservation to draw their new town — in a new territory of a new nation — into this conversation. They gave the earthworks Latin names and touted them as evidence of laudable predecessors who had mysteriously disappeared or migrated to South America. As monumental centerpieces of town squares, Putnam and his men implied that a place on the western fringes of the United States might once again grow into an urban center of American empire.

Putnam’s urban planning denied contemporary indigenous residents’ historic connections to Ohio lands. In the same breath, land company leaders preserved indigenous earthworks and displaced indigenous people. At the very same meetings where they designated those earthworks as ancient monuments, they plotted military action against Shawnee, Miami, and Wyandot confederations that resisted U. S. claims to Ohio lands. Landscape design in the midst of war was not fanciful escapism; it was a strategy of settler colonialism.

By framing indigenous earthworks as American antiquities and urban monuments, men like Rufus Putnam painted a picture of U. S. westward expansion in which migrants peacefully inhabited an abandoned landscape and contributed to the ongoing, progressive development of the American continent. This vision omitted the violence, destruction, and contested land claims that characterized the Ohio country in the territorial era. Indigenous residents of the Ohio country had no place among the public for whom Marietta’s founders claimed to be preserving American history.

Today, many of these earthworks still stand in Marietta. They retain the Latin names given to them by Putnam and his associates and sit amidst public green spaces owned by the town. A grassy tract, once lined by mounded walls, leads northeast from the Muskingum River to a platform mound in an open park. A public library sits atop a similar earthwork nearby. Mound Cemetery, founded soon after the town, surrounds a conical mound. A few historic markers nod to the indigenous architects of the earthworks. But as a whole, the cityscape frames these earthworks through the eyes of generations of colonizers, who shaped them to meet the needs of a public good that excluded indigenous Americans.