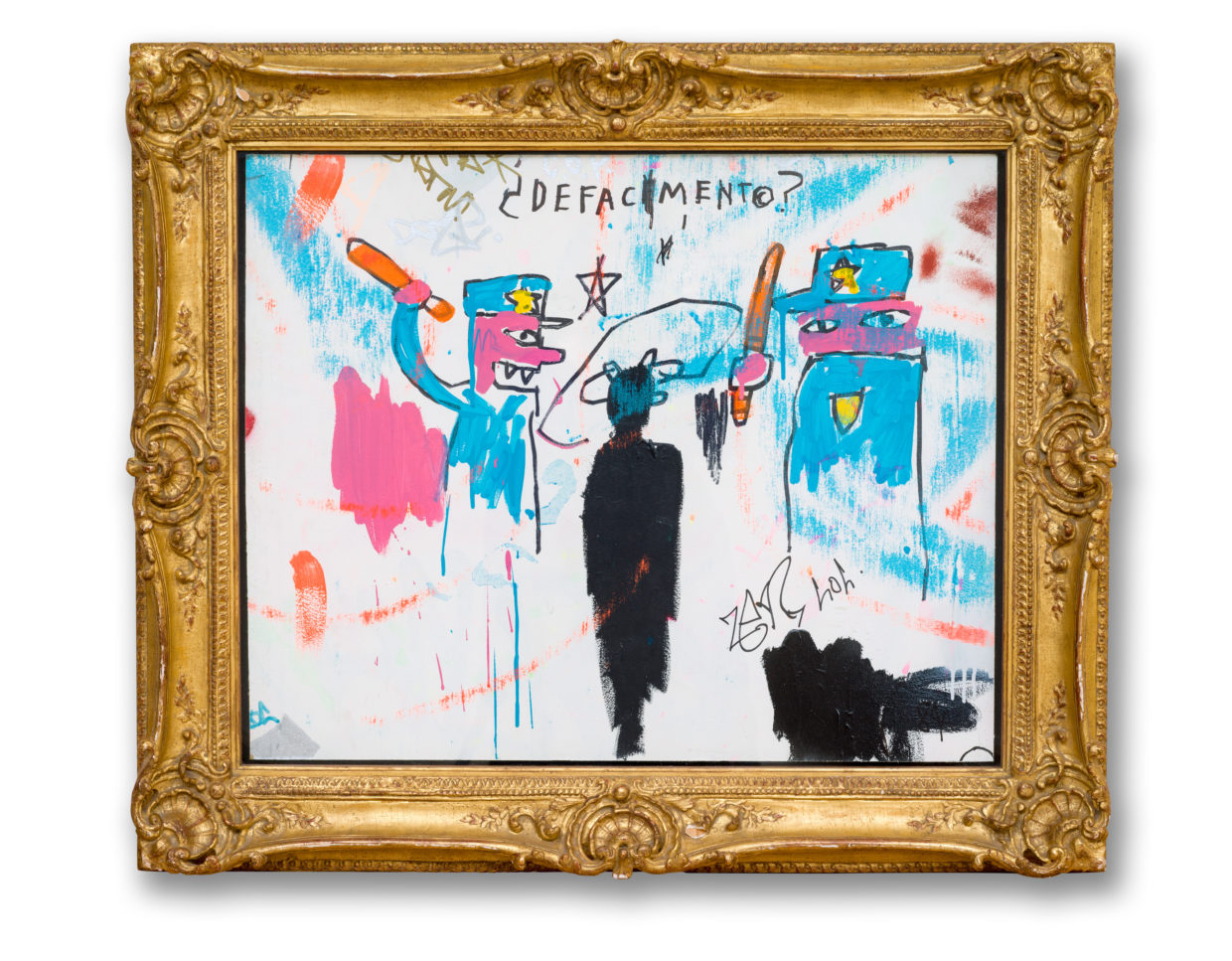

In 1983 on the Left Coast, Adolph Lyons, a 24-year-old black man, sued the Los Angeles Police Department for placing him in a chokehold, in City of Los Angeles v. Lyons. Although the Supreme Court denied Lyons’s claim, the case created a legal precedent and discourse on chokehold practices in law enforcement. Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court justice, wrote in dissent, “It is undisputed that chokeholds pose a high and unpredictable risk of serious injury or death. Chokeholds are intended to bring a subject under control by causing pain and rendering him unconscious. . . . The result may be death caused by cardiac arrest or asphyxiation.”

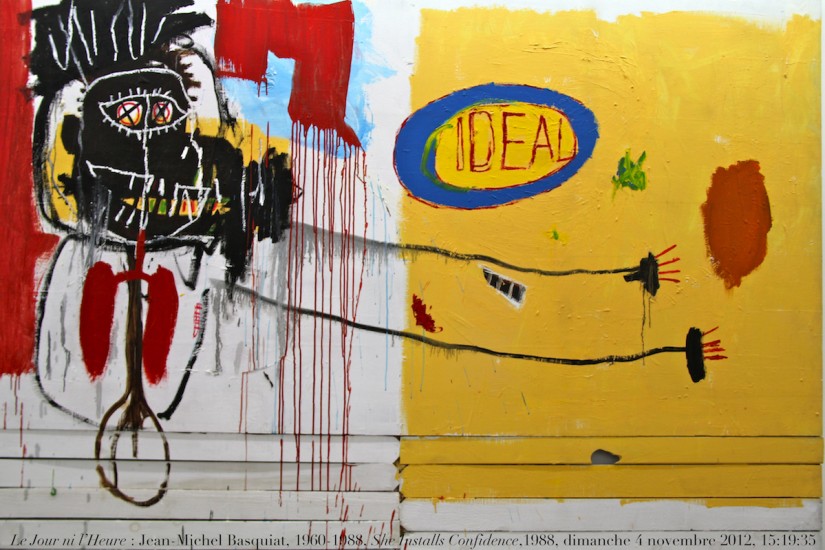

In the same year of 1983, Michael Stewart, a 25-year-old black man in New York City, died of the hypothetical yet “undisputed” sequence noted by Justice Marshall—police chokehold, asphyxiation, cardiac arrest, coma, and then death. Thirty years and eleven mercy pleas later, Eric Garner suffered the same fate. In 2014 Broken Windows policing killed Eric Garner. Zoom back to the future in 1983, when transit officers beat Michael Stewart over his entire body of a mere 140 pounds.

According to Jennifer Clement’s Widow Basquiat, based on Suzanne Mallouk’s account of her relationship with Basquiat, “[Stewart’s] face is covered in small cuts and bits of glass are visible in his flesh.” The city’s chief medical examiner, Dr. Elliot M. Gross, first reported to the press that the cause of Stewart’s death was cardiac arrest, with no evidence of beating.

Forensic pathologists that worked on behalf of the Stewart family found the final cause of death to be strangulation by an illegal chokehold with a nightstick, and a massive brain hemorrhage. To bleach evidence of the blood veins in the eyeballs indicative of hemorrhage, Gross removed them and placed them in a formalin solution so they might become as blindingly white as the lies that construct and reproduce white supremacy.

Stewart belonged to the downtown scene, but his humanity would be claimed citywide. As graffiteros would say, Stewart’s spirit went ALL CITY. His death catalyzed a civic moral reckoning against the drumbeats of Reagan’s moralistic culture wars. Graffiti became the cipher for straw-man arguments used to justify police violence. In response to the tragedy, Keith Haring created a large mural titled Michael Stewart—USA for Africa (1985). Haring’s imagery connects the police strangulation of Stewart to the violence of South Africa’s apartheid regime. The anti-apartheid struggle had become a site of burgeoning Afro-diasporic internationalism and global protest through a disinvestment movement.