While many writers have rightly dismissed the “racist bone” fallback as nonsensical and metaphorically counterintuitive, especially given the history of pseudoscientific fields such as phrenology, few have explored the genealogy of the phrase itself. Excavating the development of this knee-jerk defense helps illuminate how mainstream Americans understand race, racism and the ideology of colorblindness — as well as the dangers of this understanding.

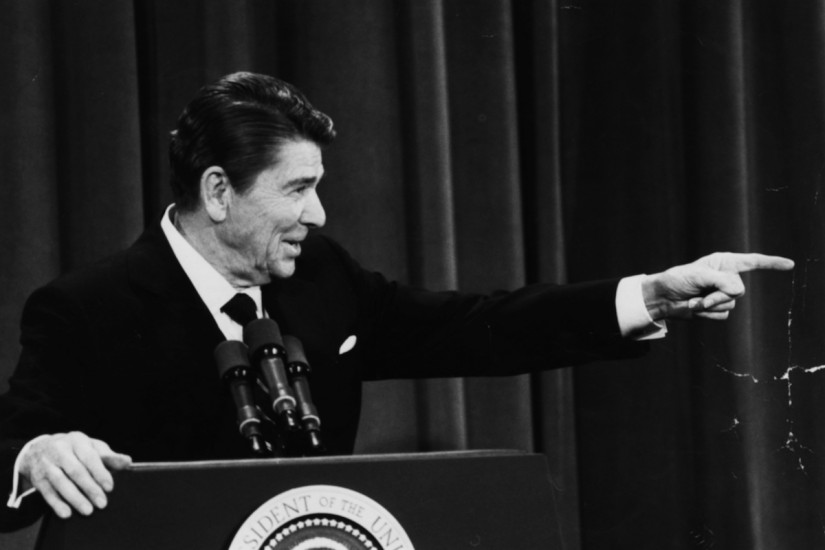

When it comes to this now ubiquitous defense, all roads appear to lead back to Ronald Reagan’s years in the Oval Office. Though there are piecemeal and disjointed references to the “racist bone” apologia dating back as early as the mid-20th century, its usage was neither frequent nor systemic until Reagan’s first term. Based on a Google Ngram search, the documented frequency of the “racist bone” defense grew most quickly between 1981 and 1986 and almost always applied to Reagan or someone in his administration.

Hatch invoked the trope multiple times to defend Reagan. In one case, Attorney General William French Smith joined Hatch in asserting that Reagan did not have “a racist bone in his body.”

The “racist bone” defense did not just apply to individuals: In 1983, during a hearing before a House subcommittee, a Republican representative remarked that “there is not a racist bone in the administration’s body.”

Republicans felt compelled to offer this defense because Reagan and his administration confronted regular accusations of racism based on their efforts to eliminate civil rights laws and their opposition to new ones. They framed their opposition to civil rights laws as part of their commitment to an exclusively “colorblind” approach to the law, wrapping themselves in the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s supposed dream of a country in which individuals are judged “not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Reagan quoted King’s alleged colorblind dream so often that, near the end of his first term, Diane Camper of the New York Times deemed the rhetorical move “The Reagan Race Phonograph.”

This embrace of colorblindness — a selective and distorted reading of what King actually advocated — enabled Reagan to frame his relentless attacks on civil rights as motivated by a morally righteous and apolitical commitment to equality. In doing so, Reagan was adopting a tactic that white anti-busing segregationists and affirmative action opponents had developed during the prior decade. This tactic emerged in a climate in which explicit racism was no longer openly tolerated in U.S. politics, but white Americans remained uncomfortable with and opposed to the policies necessary to ameliorate decades of racial discrimination.