In the United States, the conventional narrative assumes that for much of 19th century, invention was the province of heroic individuals like Edison, Colt, Singer, Morse, Bell, and so on. Their very names conjure up images of their inventions. But then, in the early 20th century, so the narrative goes, the locus of invention shifted away from these intrepid figures to anonymous teams, with the well-funded corporate research laboratory becoming the wellspring of novelty and innovation. By the 1930s, invention had been replaced by “research and development” (R&D), now the province of companies like DuPont, AT&T, and General Electric. The individual inventor — once heralded as the “genius in the garret” — was unable to compete. Marginalized, he — and, yes, it was almost always a “he” — was invisible, and ultimately doomed in the expanding marketplace for inventions and ideas.

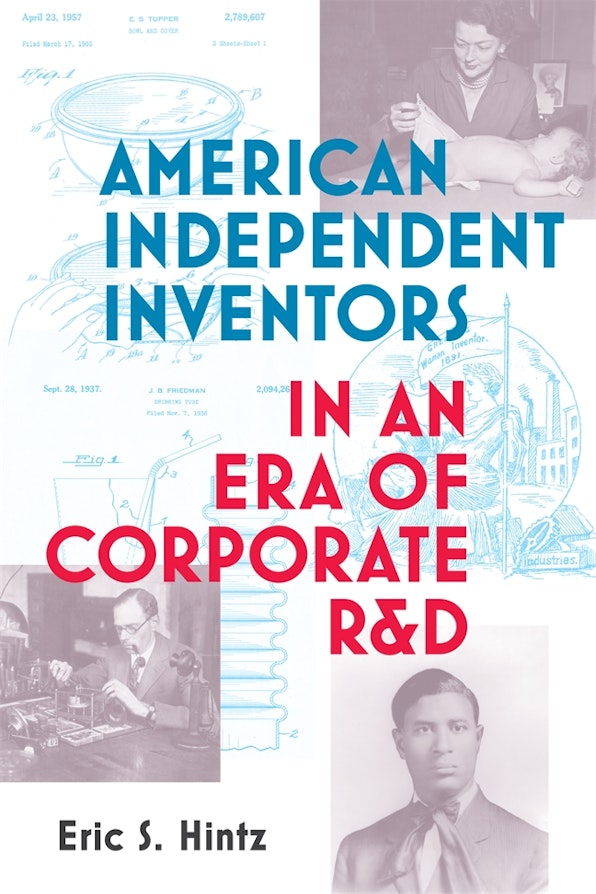

Eric S. Hintz’s new book, American Independent Inventors in an Era of Corporate R&D, offers a persuasive counternarrative. His goal, achieved via case studies based on a wide array of historical sources, is straightforward: to show that independent inventors did not vanish. This is an important claim. The United States has long touted a certain pragmatic and inventive quality as endemic to its national character. So, who is actually doing this inventing? Is it individuals (white men only, or also women and people of color), or is it corporations? This matters for questions of identity, and obviously also for questions of economics. A historian at Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation (part of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History), Hintz explains that the road independent creative people traveled was neither smooth nor easily navigated, but it offered a pathway to fortune, if not always fame. Moreover, the community of individual inventors, long depicted as composed only of tenacious, practical, and resourceful white men, was much more diverse in terms of race and gender than is commonly understood.

Who pronounced individual inventors extinct if they weren’t? The public relations and advertising industry was in fact mostly to blame. Corporate R&D labs emerged at the same time as the professional PR firms, and, as Hintz explains, the “former eagerly employed the latter.” Through radio shows, newspaper articles, and advertisements, the industry disseminated an image of corporate labs as inventing the future through their research and products. This image, sold to consumers as well as politicians and regulators, served to marginalize the independent inventor, even as some of that figure’s trappings — rolled-up shirt sleeves, late nights in the laboratory, maybe a flask cooking away on a Bunsen burner — were appropriated to humanize a new breed of company worker.