Newsletters are in again, provoking anxiety about whether they will finally kill off newspapers once and for all.

Dozens of famous authors, journalists and scholars have started online newsletters, in some cases abandoning premier platforms like the New York Times and Vox. Top newsletter authors reportedly bring in millions, with some securing hefty advances at platforms like Substack. Original essays and cultural commentary are typically delivered via email, with creators seeking payment in monthly fees rather than through advertisement revenue. Paid subscribers can also enjoy upgrades like exclusive content, meet-and-greets or access to members-only comment sections.

But newsletters do more than enrich creators and entertain readers with specialized content, and this recent uptick in interest is by no means a new phenomenon.

History shows that newsletters build political communities by generating a shared set of stories and ideas and highlighting voices ignored by the mainstream media.

Fanzines, or zines, a genre of newsletters created by and for fans of science fiction in the 1930s, connected enthusiasts of niche topics. Often self-published by a single editor, “zinesters” shared stories, commentary, artwork, fan fiction and poems related to topics of mutual interest.

Early zines were mimeographed — a cheap duplication process that forces ink through a stencil. Zinesters also used typewriters, making copies with carbon paper. They rarely made money creating and distributing zines, but gained in other ways — forming meaningful social connections, gaining respect or notoriety in fandom communities and finding satisfaction from bypassing or subverting mainstream media culture to create something wholly original.

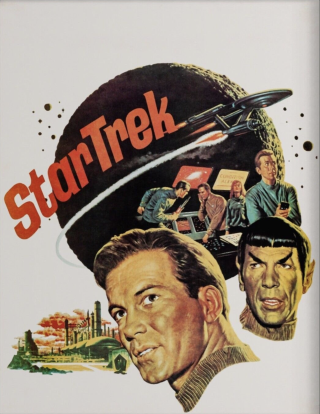

For example, the first issue of Spockanalia, a “Star Trek” fanzine launched in 1967, included a letter from actor Leonard Nimoy, an editorial describing a fan’s campaign to save “Star Trek” from cancellation and a poem called “The Territory of Rigel.” Spockanalia lasted just three years, but by then the fan base had spawned dozens of zines, such as ST-Phile and T-Negative (named for Spock’s blood type).

Zines offered a way for fans to find one another and share their love of the series, providing a worldwide community that otherwise had few means of connecting. Trade and barter of zines, recordings, fan fiction, art and photographs were also common ways for “circles” of fans to bond. Circle members might travel for hours to attend “lay-around” gatherings, where they would socialize, read fanzines and create norms to guide the community they were building together. Dedicated fans sometimes relocated to be closer to their circle, with fandom communities providing housing and job leads.

“Star Trek” zines were mailed out to subscribers for a fee, often little more than the cost of production. Creators tried to have a new issue printed and ready to sell at conventions, another important way of gaining audience members. Because they were created and distributed by fans, most of whom did not have professional editorial experience, fanzines struggled to sell advertisements. Indeed, most folded due to lack of funding and the laborious nature of self-publication methods in that era. When ST-Phile ended in 1968 after just two issues, the editors explained, “We certainly have not grown tired or disenchanted with Star Trek, but producing this fanzine has become too much of a chore.”

Zines focused on a wide variety of topics — music, comics, horror and the punk scene, to name a few. In the 1990s, the Riot Grrrl movement — a mash-up of feminist and punk sensibilities — created zines that addressed topics not covered in typical “women’s” magazines. Zines like Bikini Kill and Girl Germs challenged sexism in punk subcultures and encouraged grrrls to form local support chapters. Bikini Kill’s second issue, distributed in 1991, declared, “we hate capitalism in all its forms and see our main goal as sharing information and staying alive, instead of making profits.” Zinesters promoted grrrls’ public expression yet intentionally avoided mainstream media, viewed as complicit in women’s oppression. Subscribers gained access to exclusive content on the music, culture and organizing tactics of nascent Third Wave of feminism.

Riot Grrrl zines were photocopied and hand-stapled, and like “Star Trek” fanzines of earlier decades, most did not last long. Zines’ countercultural stance and aversion to making money from subscribers worked against their long-term survival. With few exceptions — including still-existing magazines Bust and B---- — zinesters whose products became “real” magazines, or who “sold out” to a publishing house to gain wider distribution, risked condemnation.

Newsletters have also played a role in mobilizing voters. Phyllis Schlafly, founder of the 1970s STOP-ERA campaign (“Stop Taking Our Privileges with the Extra Responsibilities Amendment”) and newsletters The Phyllis Schlafly Report and Eagle Forum, helped to kindle ideological opposition to the feminist-backed Equal Rights Amendment, which was not ratified by the 1982 deadline despite previously enjoying wide public support. Newsletters were central to building political opposition. Schlafly urged her readers to oppose the ERA because it allegedly threatened women’s “special privileges,” such as exemption from military duty, separate-sex restrooms and preference in custody disputes. Newsletter articles demonized second-wave feminists as “arrogant” and “anti-male.” According to Schlafly, “American women never had it so good.”

Schlafly’s newsletter gained a loyal following — 80,000 at its peak — of mostly conservative women ready to lobby state legislators as homemakers eager to defeat the ERA.

Feminist organizers countered Schlafly’s arguments in their own newsletters, as readers on both sides of the ERA debate turned to alternative media to gain knowledge about the movement, access organizing strategies and signal their association with a set of shared values.

Today’s online newsletters have a different — arguably more successful — distribution and payment system, but their value for readers is much the same. We are socialized to think of readers in economic terms, as consumers, without always interrogating what this means in the context of media content. Rather than bemoan the threat newsletters pose to legacy media, we can recognize the long history of alternative media in providing a space for belonging, a shared sense of purpose and access to communities — whether in person or online — that buoy our resilience.