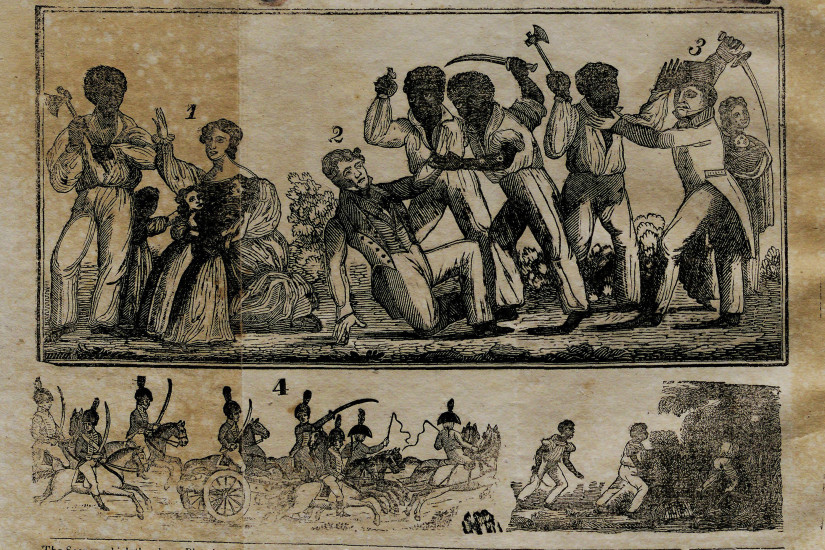

In the early hours of August 22, 1831, a slave named Nat Turner led more than fifty followers in a bloody revolt in Southampton, Virginia, killing nearly 60 white people, mostly women and children. The local authorities stopped the uprising by dawn the next day. They captured or killed most of the insurgents, although Turner himself managed to avoid capture for sixty days.

Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. In a letter written a month later from North Carolina, Nelson Allyn described the retaliation against African Americans:

"The insurrection of the blacks have made greate disturbance here every man is armd with a gun by his bed nights and in the field at work a greate many of the blacks have been shot there heads taken of stuck on poles at the forkes of rodes some been hung, some awaiting there trial in several countys, 6 in this county I expect to see them strecht ther trial nex week there is no danger of their rising again here."

Nineteen of the thirty who had been arrested were convicted and executed. The rest, along with 300 free blacks from Southampton County, agreed to be exiled to Liberia in Africa. Turner was hanged on November 11, 1831.

Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slave states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write.

A full transcript of Nelson Allyn's letter is available below.