As a child, I knew only that my grandmother had died when my mom was still a baby. The one time I asked what had happened to her, a bolt of panic flashed across my mother’s face. “A household accident,” was all she said.

I was twelve years old when she finally told me the truth. Some friends and I had got into a long after-school discussion about abortion, prompted by the gruesome posters that a protester had staked in front of the Planned Parenthood in our Vermont town. I had already begun reading my mother’s Ms. magazines cover to cover, but this was the first time I’d encountered a pro-life position. When I hopped into my mom’s car after school, I was buzzing with new ideas. I had almost finished repeating one friend’s pro-life argument when I saw the look on Mom’s face. That’s when she told me: the “household accident” that had killed her mother had, in fact, been a self-induced abortion.

Her hands were tight on the steering wheel as she spoke. I realized later that it wasn’t the topic of abortion itself that made her so uneasy—she was a nurse and a Roe-era feminist who usually responded straightforwardly to even the most embarrassing health questions. Rather, her anguish arose from sharing a truth that she’d been brought up believing was too terrible to speak.

Sitting beside her in the passenger seat, I struggled to absorb the meaning of what she’d told me. I had only just grasped what abortion was a few hours earlier, and was still trying on this new pro-life idea. “O.K.,” I said, “but what about the uncle or aunt I never had?” Mom whipped toward me, face taut with a rage and fear that I somehow understood had nothing to do with me. “What about the mother I never had?” she said.

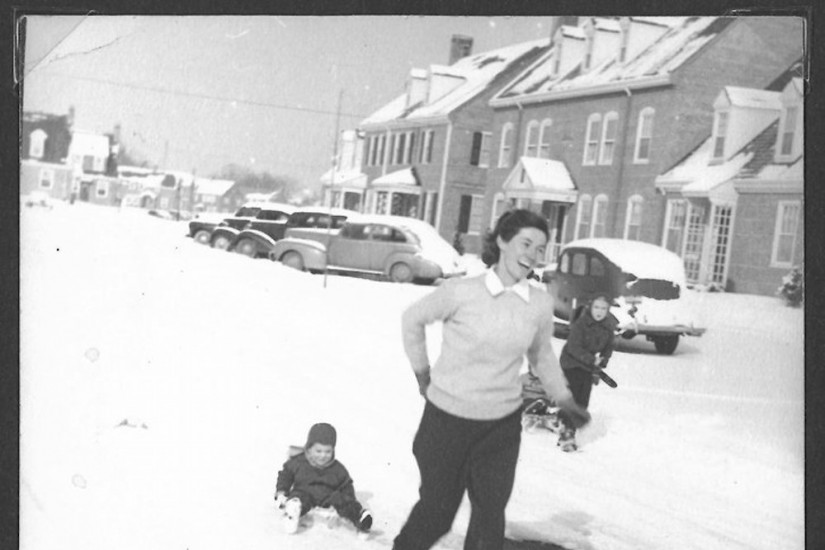

Until recently, everything my mom knew about her mother fit into one three-ring binder. Inside were letters, documents, and photos that my mother had collected over the years. After the election last fall, as an Administration hostile to women’s reproductive rights settled into the White House, I asked her to send the binder to me, and did some sleuthing of my own. I got in touch with aging relatives and family friends, who offered crumbling bundles of my grandmother’s letters, carefully preserved for decades. My questions about her life and death hadn’t changed since I was twelve years old. What felt new, in the Trump era, was the urgency of her story.