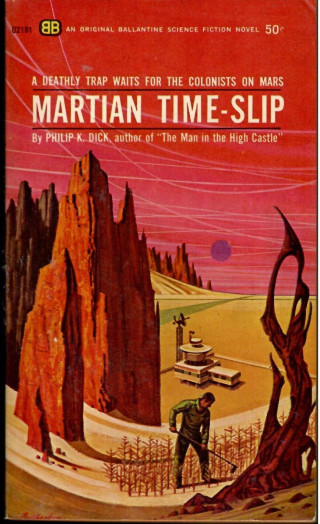

Imagine a present-day reader reaching for Philip K. Dick’s 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip in search of transport, out of the here and now to a psychedelically paranoid near-future Mars. This person might be disconcerted to find two characters discussing traveling to a zone called New Israel—specifically, to a Martian settlement called Camp Ben-Gurion:

As Otto and Steiner walked back to the storage shed, Steiner said, “I personally can’t stand those Israelis, even though I have to deal with them all the time. They’re unnatural, the way they live, in those barracks, and always out trying to plant orchards, oranges or lemons, you know. They have the advantage over everybody else because back Home they lived almost like we live here, with desert and hardly any resources.”

“True,” Otto said. “but you have to hand it to them; they really hustle. They’re not lazy.”

“And not only that,” Steiner said, “they’re hypocrites regarding food. Look at how many cans of nonkosher meat they buy from me. None of them keep the dietary laws.”

“Well, if you don’t approve of them buying smoked oysters from you, don’t sell to them,” Otto said.

Then, a page later:

Steiner felt guilty that he had talked badly about the Israelis. He had done it only as part of his speech designed to dissuade Otto from coming along with him, but nevertheless it was not right; it went contrary to his authentic feelings. Shame, he realized. That was why he had said it; shame because of his defective son at Camp B-G … Without the Israelis, his son would be uncared for. No other facilities for anomalous children existed on Mars …

When Dick became my chosen writer, at age fourteen, in 1978, with Martian Time-Slip, one of my two or three favorites among his novels, the presence of the Israeli settlement on Mars didn’t resound in any particular way. My initial responsiveness to Dick’s work was to delight in his mordant surrealist onslaught against the drab prison of consensual reality—he was punk rock to me. It took me a while to grasp how Dick’s novels, those of the early sixties especially, function as a superb lens for critiquing the collective psychological binds of the postwar embrace of consumer capitalism. Yet to say that he seems to devise his critiques semiconsciously, by intuition, is an understatement. Dick thought he was bashing out pulp entertainment, and he sometimes despised himself for doing it. At other times—and Martian Time-Slip was one of those times—he injected his efforts with the aspiration to raise his output to the condition of literature, employing all the thwarted ambition of a young novelist with nine or ten literary novels (or, as an SF writer would put it, “mainstream” novels) in his trunk, which his agent had been unable to place with New York publishers. Dick had an extrasensory power, however; he was a freaked-out supertaster of repressive and coercive elements lurking inside the seductive and banal surfaces of Cold War U.S. culture and politics. This meant that science fiction opened up his particular capacity for fusing ordinary experience—the emotional and ontological crises of his human characters—to the implications of the hegemonic power of the U.S., which coalesced in the period in which Dick wrote, and which defines our present century. Reality’s surface shimmers open beneath Dick’s gaze. It’s this that led Fredric Jameson to compare him to Shakespeare. This wouldn’t have happened had he stuck to the earnest social realism of his unpublished novels.