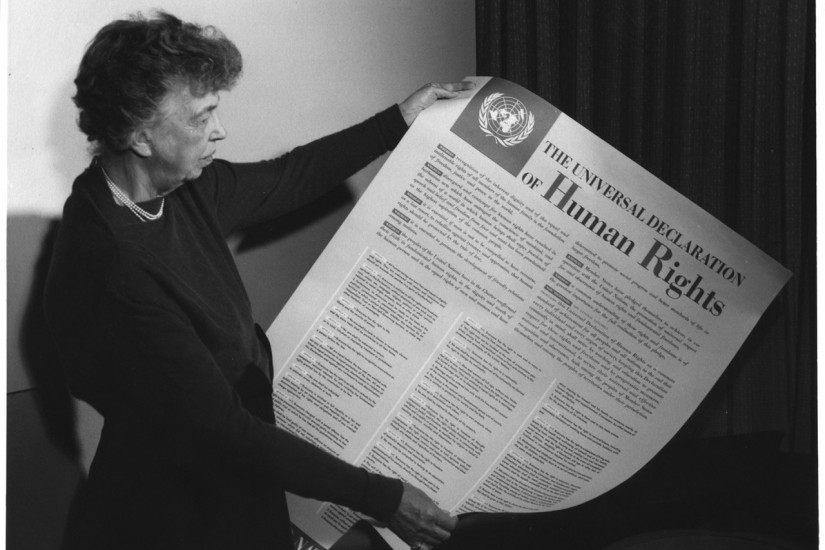

Without the leadership and vision of Eleanor Roosevelt it is unlikely that the Universal Declaration could have been completed and accepted by all but a few governments. In those early postwar years she occupied an incomparable position on the international scene. She was not just a great president’s widow; she became, in her own right, almost a force of nature, a figure of majestic wisdom and simplicity. Glendon quotes E.J. Kahn’s description of her, “a person of towering unselfishness”—a quality that by itself set her apart from the striving national statesmen of the time.

When she boarded the Queen Mary in New York in January 1946 as a member of the US delegation to the first session of the UN General Assembly in London, Eleanor Roosevelt was embarking on a new career in which neither she nor the State Department had any great confidence. It is true that she had, both publicly and behind the scenes, been more intensively involved in political and international affairs than the wife of any other modern president; she had, for example, suggested that black advisers be added to the US delegation at the 1945 San Francisco Conference. But she had no formal diplomatic experience and was assigned to the General Assembly’s committee on social questions because State Department officials believed it would be less challenging and difficult for her than joining the political committees. Their anxiety soon proved to be mistaken. Ralph Bunche, who was also a member of the delegation, quickly came to the conclusion that, in a group that included Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, John Foster Dulles, and Senator Arthur Vandenberg, all of whom tended to play political games, Mrs. Roosevelt was the only member with a genuine sense of responsibility, who listened to her advisers and conscientiously did her homework.

Any idea that Mrs. Roosevelt might not be up to dealing with difficult foreign representatives soon proved to be absurd. Her dignity, mastery of the subject matter, courtesy, and, when necessary, invincible firmness vanquished even the most redoubtable opponents. I remember vividly her later encounters with Andrei Vishinsky over the fate of European refugees from the war. Vishinsky, the vitriolic public prosecutor in the Soviet show trials of the 1930s, was a highly abusive and almost unstoppable orator. He had a shock of white hair and an unhealthy-looking pale complexion that turned bright red when he was angry or frustrated. “Mr. Vishinsky,” Mrs. Roosevelt would say in the maternal tone of one correcting an errant child,

We here in the United Nations are trying to develop ideas which will be broader in outlook, which will consider first the rights of man, which will consider what makes man more free. Not governments, Mr. Vishinsky, but man.

Vishinsky would turn beet red, but, for once, was at a loss for words.