In his book On Compromise and Rotten Compromises, the philosopher Avishai Margalit argues that “we should be judged by our compromises more than by our ideals and norms. Ideals may tell us something important about what we would like to be. But compromises tell us who we are.” The essence of popular government rests on the idea that compromise is not only necessary, but that it is a positive function in promoting the interests of the public good. Margalit warns, however, that political compromises can easily lead to immoral and violent outcomes. He defines a “rotten political compromise” as one that helps “establish or maintain an inhuman regime, a regime of cruelty and humiliation . . . that does not treat humans as humans.” This provocative definition might compel students of nineteenth-century U.S. history to consider numerous instances of political compromise when slaveholders’ interests were perpetuated in the interest of national harmony.

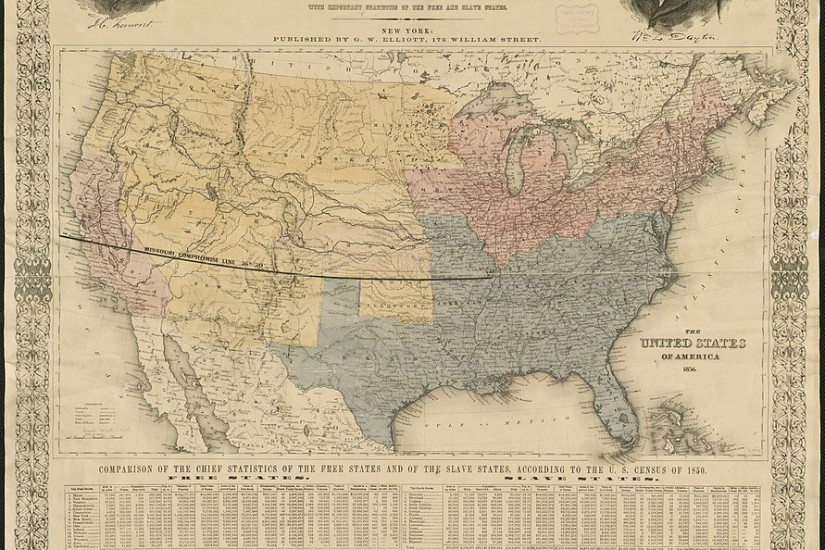

One such moment that I have been studying more lately is the Missouri Compromise of 1820. As we approach the 200th anniversary of this crucial legislation, I have taken an interest in studying figures who refused to compromise on the question of slavery’s existence in the new state of Missouri. In particular, I have been fascinated by the responses of a small number of Missourians who unsuccessfully fought to ban slavery in the state.

The Missouri Compromise story is well-known to nineteenth-century historians. A bill on Missouri statehood was first brought up for debate in Congress on December 18, 1818. Fearing the rapid spread of slavery into new western territories, Congressman James Tallmadge of New York proposed a plan to gradually end slavery in Missouri. Any black Missourians born after statehood would be free and the remaining enslaved population in the state would be gradually emancipated over time. Senator Jesse B. Thomas of Illinois proposed a further amendment to ban slavery north and west of Missouri in other territories that were part of the Louisiana Purchase, a precursor to the final legislation that Congress would eventually pass.

These proposals caused such a furor among proslavery politicians—not least Missouri’s own proslavery leaders—that the Missouri statehood bill failed to pass before Congress adjourned in March 1819. John Scott, Missouri’s non-voting representative in Congress, complained that his prospective state was entitled to the “rights, privileges, and immunities enjoyed the other states.” Dismissing earlier Congressional legislation banning slavery in the Northwest Territory, Scott argued that as long as a republican form of government for white men was established in Missouri, Congress could not interfere any further. If Congress could ban slavery in Missouri, it could also establish “what religion the people should subscribe . . . and to provide for the excommunication of all those who [do] not subscribe.” Slavery had existed in Missouri territory for one hundred years at that point and should be allowed to exist moving forward, according to Scott.