When my grandmother died from a mucosal melanoma (a form of skin cancer) in 2015, I sat around with my mother and my aunts talking through the wording of the email we were going to send round to her friends and colleagues to inform them of her death. We rejected the obvious line, “She died after a long battle with cancer,” because we felt it implied a failure on her part — a conflict lost because she hadn’t tried quite hard enough. It struck me, however, how difficult it was to come up with alternative wording and how ingrained such military metaphors are in our semantics of cancer.

I was reminded of this very personal moment while watching the very public fall-out of Senator John McCain’s glioblastoma diagnosis. McCain received messages of support and sympathy from across the political spectrum, many of which drew on this ingrained language and traded on an adversarial model of the cancer experience. President Barack Obama tweeted, “John McCain is an American hero & one of the bravest fighters I’ve ever known. Cancer doesn’t know what it’s up against. Give it hell, John.” Obama was not alone in drawing on McCain’s military background, weaving his martial history into his medical present and positioning cancer as an identifiable and malevolent foe.

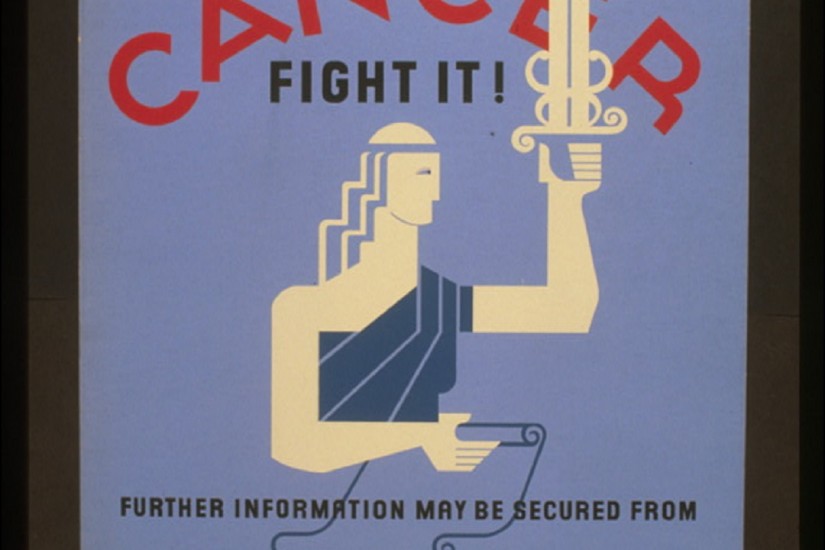

Military metaphors are a familiar part of the semantics of cancer that operate in today’s world. On a national or even global scale there is a “fight” or “crusade” against cancer; on an individual level cancer is the “killer” disease and people who have cancer are “cancer victims.”1 Obituaries record people who died after a “long battle,” friends recall their loved ones’ “fighting spirit,” and efforts to “beat” malignancy. And nowhere is this more manifest than in President Richard Nixon’s promise to “conquer” the disease in his still un-won “war on cancer.”2