“MY MOTHER POSSESSED A SUPERLATIVE ASHTRAY,” writes architecture critic Catherine Slessor. It had a waist-high stand and a chrome-plated bowl, and, she writes, “faintly reeking, it stood to attention in our 1960s suburban living room like some engorged trophy.” Slessor goes on to describe other ashtrays of note: a Limoges porcelain limited-edition ashtray that Salvador Dalí designed for use on Air India, in exchange for a baby elephant that the airline transported for him from Bangalore to Spain; the ashtrays at Quaglino’s in London that reportedly used to disappear at a rate of seven per day in the 1990s, snatched by diners as souvenirs of a society locale. In doing so, she conjures the material world of the twentieth century, inhabited as it was by ashtrays of all shapes and sizes. Then, with the dawn of the millennium, this category of object—part functional décor, part objet d’art—all but disappeared.

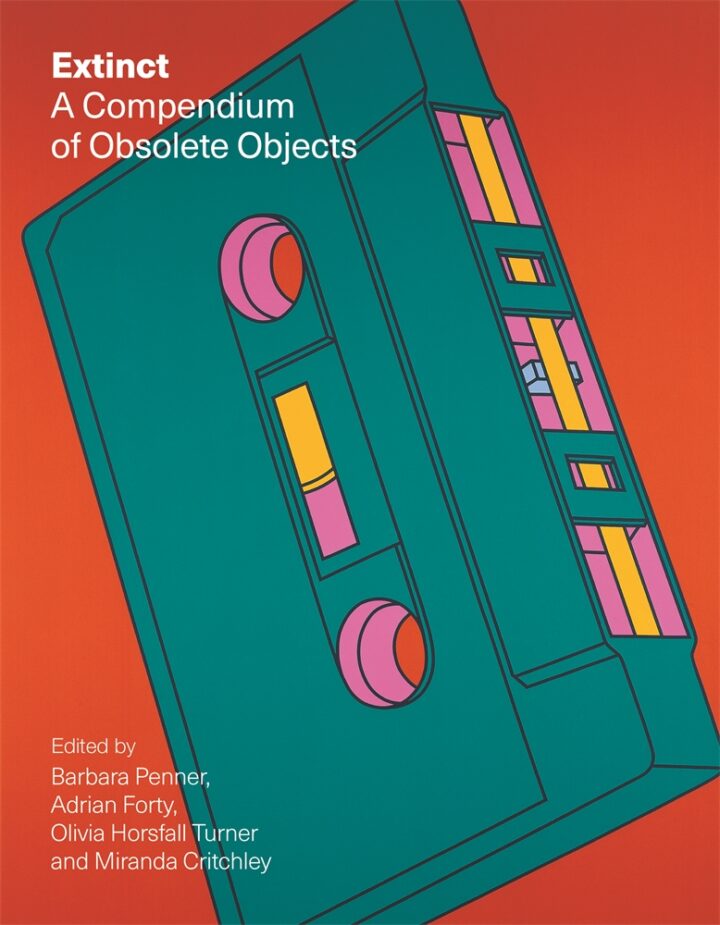

Slessor’s short essay on the ashtray appears in the new book Extinct: A Compendium of Obsolete Objects, a collection of illustrated essays on eighty-five objects that, its editors write, “once populated the world and do so no longer.” To skim its table of contents is to encounter a wide-ranging catalog of lost things: all-plastic houses, cab fare maps, chatelaines, flying boats, moon towers, paper dresses, slide rules, UV-radiated artificial beaches, zeppelins. It is pointedly open-ended, inclusive of infrastructure and architecture as well as personal effects. The only unifying criterion is what its editors term “extinction,” in a self-conscious nod to Darwin-inflected evolutionary theories of technological innovation. “When things disappear, they do so, it is implied, because of their own inadequacy or their unsuitedness to their conditions. Part of the purpose of this book is to probe and question this seeming inevitability,” they write in the introduction. The word “extinct” also connotes something else, more poignant than “obsolescent”: a nod to the kind of death that can happen to our things. It is a loss more profound than many of our words for it—waste, breakage, consumption, discarding—convey. Extinct takes these material losses seriously and tries to quantify the social effects wrought by the wholesale disappearance of particular objects.