When May’s first film role was announced, Nichols commented: “Elaine is going to suffer in Hollywood. She must have complete control of a given situation. Out there she will be at the mercy of many people.” May declined to participate in Miss May Does Not Exist, and the portrait of her that emerges here is at the mercy of her former colleagues, friends, countless journalists, and of course Courogen herself, who spoke with forty-six sources—most of them men, notably the playwright Kenneth Lonergan and May’s close friends and collaborators Phillip Schopper and Julian Schlossberg. But the most forceful testimonies in the book were given years ago: “Elaine May makes Hitler look like a little librarian,” her New Leaf costar Walter Matthau once said. “She can literally do anything she wants. Give her five minutes, and she’ll master it.” One of her ex-boyfriends: “She treated everything funny that men take seriously.” Mark Gordon, a peer from her Chicago theater days: “Elaine didn’t give a shit if the audience didn’t like her work.” Former head of Paramount Barry Diller: “She is a brilliant woman, and a wonderful woman, but she can go to jail or the madhouse for ten years before I will submit to blackmail!”

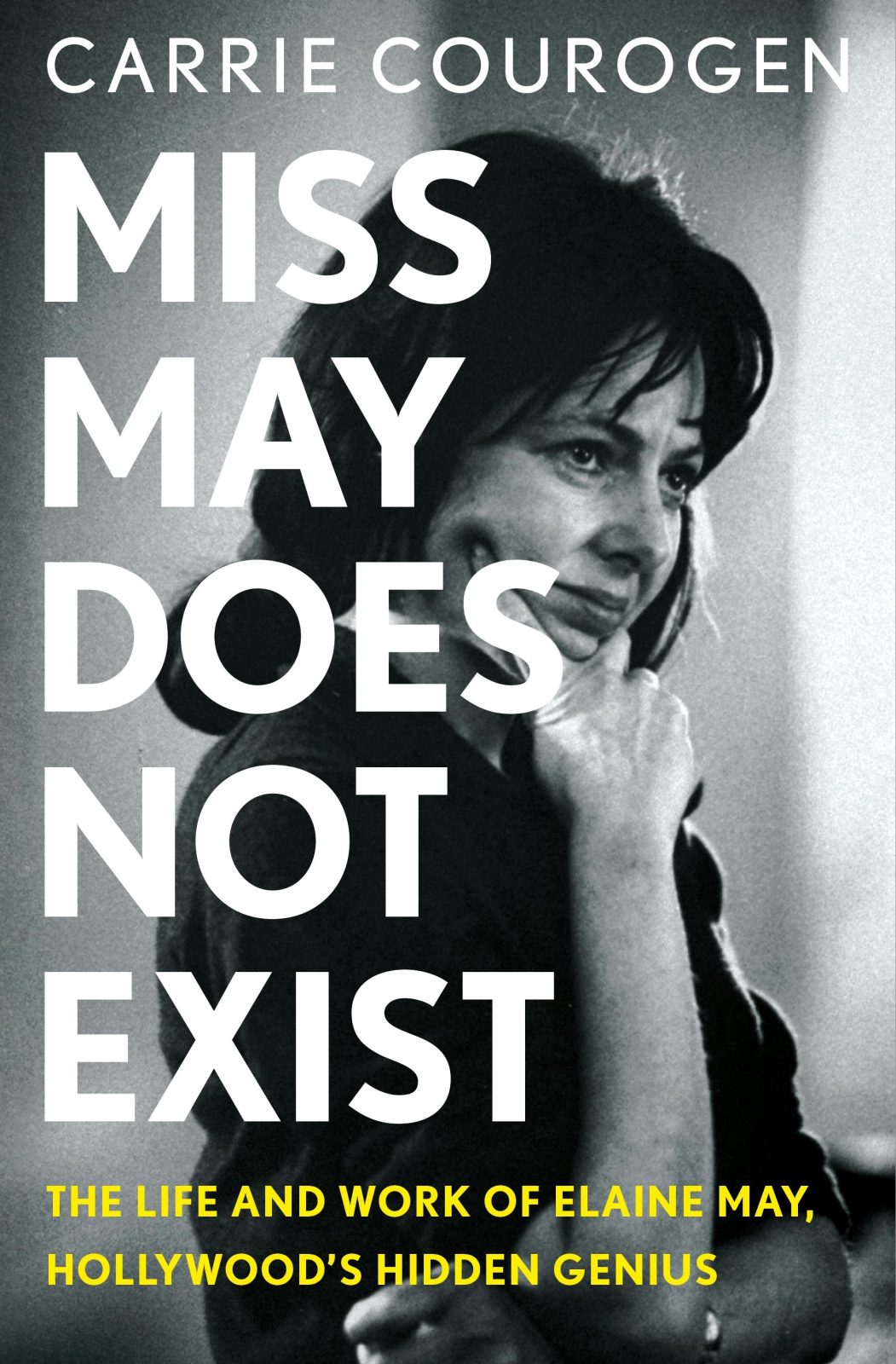

Courogen says her piece in a short prologue. She takes us back to one “crisp Tuesday evening in September.” She is sitting on a bench on Central Park West across the street from the San Remo building—where the ninety-two-year-old May has lived since 1981—trying to “subtly adjust the too-tight long blond wig on my head.” This is a stakeout. The author explains her cunning disguise: “You see, I am just as scared of being recognized by Elaine as she maybe is of me.” Why May would recognize someone she’s never met is beyond me, but this is beside the point, which is that Courogen wants us to know that she has tried everything she could think of to gain access to her subject. Courogen clearly feels seen by May. She dedicates her book to “difficult girls,” calls her subject “Elaine,” and is as familiar as May is reticent, writing in a casual yet demonstrative manner about May’s “flop eras,” her “best self,” and her “irreverent badassery.” (May is widely understood to have orchestrated the smuggling across state lines of two crucial reels from her 1976 film Mikey and Nicky, which she later used as leverage to win back control over the film when Paramount seemed poised to take over the final cut. “Why should I be loyal to a big mountain with some stars around it?” she may or may not have said.)