From the colonial era well into the 20th century, large public barbecues were an institution across the South, from the Chesapeake eventually to Texas. Although these occasions could be linked to campaigns or celebrations of one kind or another, they could also be just an excuse for people to get together, to eat and perhaps to drink, dance, and gamble, as well. (George Washington won eight shillings playing cards at an Alexandria barbecue in 1769.) Often whole communities turned out. When New Bern, North Carolina, held a barbecue to celebrate the Treaty of Paris, a Spanish visitor marveled that “there was a barbecue (a roast pig) and a barrel of rum, from which the leading officials and citizens of the region promiscuously ate and drank with the meanest and lowest kind of people, holding hands and drinking from the same cup.” He added, “It is impossible to imagine, without seeing it, a more purely democratic gathering.” A white Alabamian claimed in the 1820s that at barbecues sometimes even “slavery forgot its chain” and “the tawny sons of Africa danced, sung, and balloeed [sic].” (He denounced these scenes of “unbounded license” and called for their abolition, but nobody paid attention.)

Although big public barbecues can still be found (they’re more decorous these days), 20th-century refrigeration and automobiles made it possible to have restaurants that serve barbecue every day, not just on special occasions, and today that’s where most barbecue is eaten.

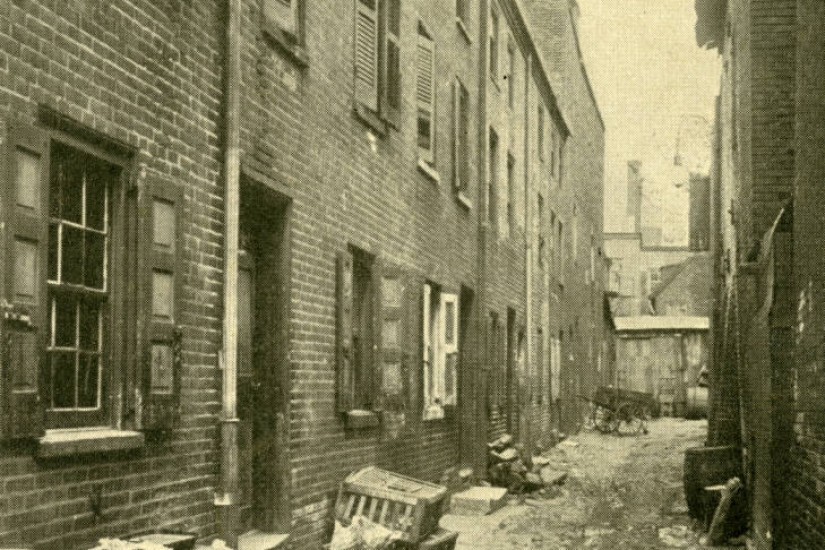

Fifty or 60 years ago it was easy to describe a typical barbecue place. At its simplest it was a workingmen’s “joint” that probably sold beer; at its fanciest it was the kind of place that attracts the after-church crowd; but often it was simply the community barbecue brought indoors, feeding customers of all sorts and conditions. Before the 1960s, of course, restaurants seated either black or white customers, not both, but many sold take-out for customers of the other race. In fact, some sold take-out only, but most had at least a few tables, perhaps as many as a score, and many had curb service. If it was on a highway, it might have had drop-in business from passers-by, but it was not a “destination”: it served the small town or city neighborhood in which it was located. Often it was owned and operated by someone whose name was on its sign and who was usually found on the premises. If it had waitresses (or, rarely, waiters), they tended to be characters. The barbecue was cooked with heat and smoke from wood or coals.