The maps were created in response to a questionnaire sent throughout New Spain in 1577 by the Office of the Cronista Mayor-Cosmógrafo. Following a decree by King Philip II, the office was to formally describe Spain’s colonial holdings. It authored, printed, and distributed a 50-item questionnaire to local officials in the Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru to gather information about the landscape and peoples. The questionnaires were returned between 1579 and 1585 and several of them were accompanied by maps made by Indigenous artists as illustrations. The responses became known as relaciones geográficas.

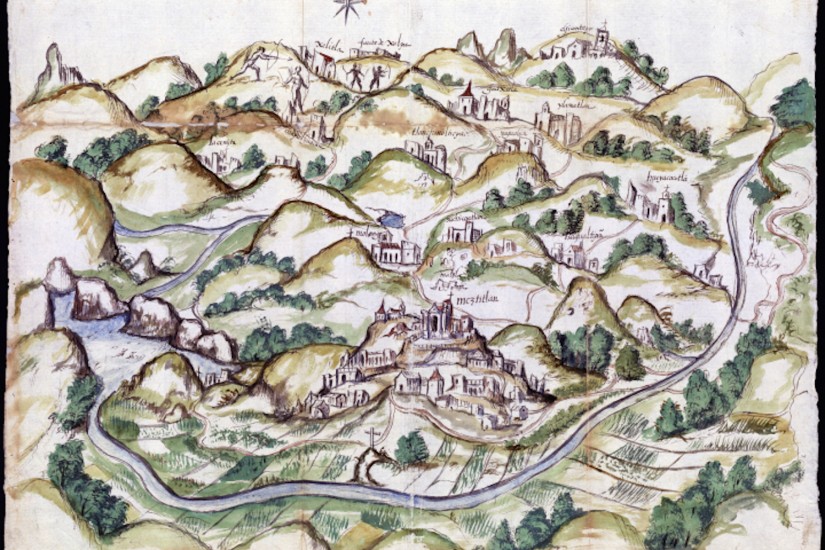

Mapping Memory shows 20 of these relaciones geográficas from the Benson Collection. There were 191 responses to the questionnaire; 43 are in the Benson Collection and more than half of those were accompanied by one or more maps, known as pinturas. Those currently on exhibit record traditions of mapmaking that demonstrate alternative uses of space to Europe’s geometry and cartographic projection. Rather, the pinturas, drawn by unrecorded Indigenous artists, show a stage created of and for human action.

“What the maps best show us is the Indigenous world — how its inhabitants, still reeling, no doubt, from the blows of conquest, reshaped their once insular maps to keep pace with the rapid changes in their understanding of the surrounding world,” historian Barbara Mundy, who is not affiliated with the exhibition, offers in The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas.

Most were created with watercolors and ink on paper, although one artist illustrating Atengo and Misquiahuala used tempera on deerskin. The style of each is unique, as are the colors and brushwork; the majority measure approximately 16 to 24 inches by 24 to 36 inches, in both landscape and portrait compositions. Some of the pinturas, however, are massive — the watercolor and ink map of the Mixtec community of Teozacoalco (in present-day Oaxaca), for example, is more than twice the size of the others.