Editor’s note: This article quotes historical sources using terms now considered racist to describe Black and Asian workers.

The recent surge in anti-Asian violence in the U.S. has put a spotlight on Asian American history, at least for a moment. “Racism is real in America, and it always has been,” Vice President Kamala Harris said on March 19, 2021. “In the 1860s, as Chinese workers built the transcontinental railroad, there were laws on the books, in America, forbidding them from owning property.”

In fact, far more Asian workers moved to the Americas in the 19th century to make sugar than to build the transcontinental railroad. It is a history that can force Americans to contend with colonial violence in the making of the modern world, dating back centuries to Christopher Columbus and his search for trade routes and quick wealth.

As I explore in my book “Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation,” thousands of Chinese migrants were recruited to work side by side with African Americans on Louisiana’s sugar plantations after the Civil War. Though now a largely forgotten episode in history, their migration played a key role in renewing and reinforcing the racist foundation of American citizenship. Recruited and reviled as “coolies,” their presence in sugar production helped justify racial exclusion after the abolition of slavery.

Empire, sugar and slavery

In places where sugar cane is grown, such as Mauritius, Fiji, Hawaii, Guyana, Trinidad and Suriname, there is usually a sizable population of Asians who can trace their ancestry to India, China, Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia and elsewhere. They are descendants of sugar plantation workers, whose migration and labor embodied the limitations and contradictions of chattel slavery’s slow death in the 19th century.

Beginning in the 17th century, the global sugar industry and slavery grew hand in hand to shape the course of capitalist development. Mass consumption of sugar in industrializing Europe and North America rested on mass production of sugar by enslaved Africans in the colonies. The whip, the market, and the law institutionalized slavery across the Americas, including in the U.S.

When the Haitian Revolution erupted in 1791 and Napoleon Bonaparte’s mission to reclaim Saint-Domingue, France’s most prized colony, failed, slaveholding regimes around the world grew alarmed. In response to a series of slave rebellions in its own sugar colonies, especially in Jamaica, the British Empire formally abolished slavery in the 1830s. British emancipation included a payment of £20 million to slave owners, an immense sum of money that British taxpayers made loan payments on until 2015.

Importing indentured labor from Asia emerged as a potential way to maintain the British Empire’s sugar plantation system. In 1838 John Gladstone, father of future prime minister William E. Gladstone, arranged for the shipment of 396 South Asian workers, bound to five years of indentured labor, to his sugar estates in British Guiana. The experiment with “Gladstone coolies,” as those workers came to be known, inaugurated what historian Hugh Tinker called “a new system of slavery,” which would endure for nearly a century.

Louisiana’s sugar bowl

Louisiana is firmly enmeshed in the global history of empire, sugar and slavery. When Bonaparte’s dream to make France great again collapsed in Haiti, he agreed to sell France’s claims in North America to the U.S. empire in 1803, in what has come to be known as the Louisiana Purchase. Plantation owners who escaped Saint-Domingue with their enslaved workers helped establish a booming sugar industry in southern Louisiana.

On huge plantations surrounding New Orleans, home of the largest slave market in the antebellum South, sugar production took off in the first half of the 19th century. By 1853, Louisiana was producing nearly 25% of all exportable sugar in the world.

Enslaved Black workers made that phenomenal growth possible. On the eve of the Civil War, Louisiana’s sugar industry was valued at US$200 million. More than half of that figure represented the valuation of the ownership of human beings – Black people who did the backbreaking labor of making sugar on a grand scale.

An 1855 print shows workers on a Louisiana plantation harvesting sugar cane at right.

Library of Congress

During the Civil War, Black workers rebelled and joined what W.E.B. Du Bois called the “General Strike,” abandoning sugar production as quickly as they could. On plantation after plantation, Black workers ran away. By the war’s end, approximately $193 million of the sugar industry’s prewar value had vanished.

Disappearing acts

Desperate to regain power and authority after the war, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters studied and learned from their Caribbean counterparts. They, too, looked to Asian workers for their salvation, fantasizing that so-called “coolies” would be cheap, industrious and submissive – a “model minority” of sorts.

Thousands of Chinese workers landed in Louisiana between 1866 and 1870, recruited from the Caribbean, China and California. Bound to multiyear contracts, they symbolized Louisiana planters’ racial hope for a new system of slavery. “We can drive the niggers out and import coolies that will work better, at less expense,” journalist Whitelaw Reid reported hearing all across the South in 1866, “and relieve us from this cursed nigger impudence.”

To great fanfare, Louisiana’s wealthiest planters spent thousands of dollars to recruit gangs of Chinese workers. When 140 Chinese laborers arrived on Millaudon plantation near New Orleans on July 4, 1870, at a cost of about $10,000 in recruitment fees, the New Orleans Times reported that they were “young, athletic, intelligent, sober and cleanly” and superior to “the vast majority of our African population.”

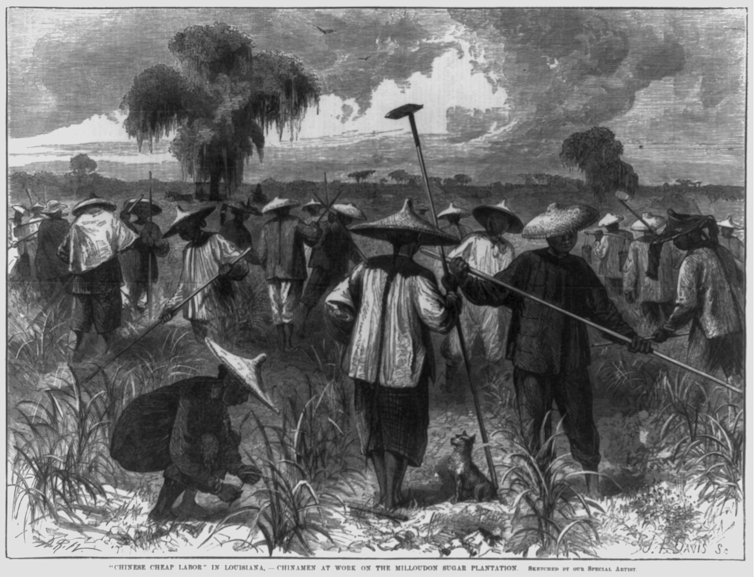

An 1871 engraving titled ‘Chinese cheap labor in Louisiana - Chinamen at work on the Milloudon Sugar Plantation.’

Library of Congress

Mostly segregated in specifically designated buildings in former slave quarters, Chinese workers generally contracted to work for wage rates far below the prevailing rate in the sugar region: around $14 per month, compared with about $20 per month that local Black men received. But the competition between Black and Chinese laborers that planters predicted did not materialize.

On the ground, Chinese workers behaved no differently from Black workers. When they heard that other workers earned more, they demanded the same. When planters refused, they ran away. The Chinese recruits, the Planters’ Banner observed in 1871, were “fond of changing about, run away worse than negroes, and … leave as soon as anybody offers them higher wages.”

Adapting to the rhythms of sugar production, where workers were in high demand during the harvest season at the end of the year, Chinese workers transformed themselves from long-term contract laborers to short-term seasonal laborers. Many moved around Louisiana throughout the 1870s, stopping over in New Orleans and other towns between stints on sugar plantations. Many others left sugar production altogether. In their search for something better, Chinese workers blended into the landscape so well that they disappeared.

But the racial image of Asian workers as industrious and submissive “coolies” making sugar on plantations stuck. When Congress debated excluding the Chinese from the United States in 1882, Rep. Horace F. Page of California argued that the United States could not allow the entry of “millions of cooly slaves and serfs.” That racial reasoning would justify a long series of anti-Asian laws and policies on immigration and naturalization for nearly a century.

This article is part of a series examining sugar’s effects on human health and culture. Click here to read the articles on theconversation.com.![]()

Moon-Ho Jung, Professor of History, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.