Nancy MacLean’s newly reissued Behind the Mask of Chivalry, three decades after its original appearance, is guaranteed to interest a new generation of scholars and activists seeking to understand the second iteration of the Ku Klux Klan, the hyperpatriotic white supremacist Protestant organization that counted between two and six million members by the mid-1920s, and the broader history of organized reactionaries in America. Best known in liberal circles for her best-selling 2017 book about post–World War II conservative thinkers and policymakers, Democracy in Chains, MacLean first earned admiration for her exploration of this earlier right-wing organization. Evidence of why her prize-winning book has aged well over the last thirty years and why Oxford University Press decided to republish it is obvious: numerous instructors continue to assign it, countless historians cite it, and the best Klan scholars have given it well-deserved praise. It is, according to another subject expert, historian Thomas R. Pegram, “the best-known and most influential single book on the 1920s Klan.” And its value isn’t only to academics: the book helps us understand some of the roots of today’s reactionary activists and policymakers.

The 2024 edition, identical to the 1994 book except for a new eight-and-half-page preface, offers brilliant insights into the Klan’s activities — how members organized, why they achieved acceptability in many quarters, and why their reprehensible activities still matter today. MacLean paints a vivid picture of the period that triggered the Klan’s rebirth, noting the expansion of big business, the outbreak of class conflicts, resistance to burdensome Jim Crow laws, and women’s push for greater personal freedoms. The Klan responded to these developments with poisonous racism, nativism, antisemitism, and sexism as well as strident calls for working-class subordination to social and economic “betters” and demands for strict moral uprightness.

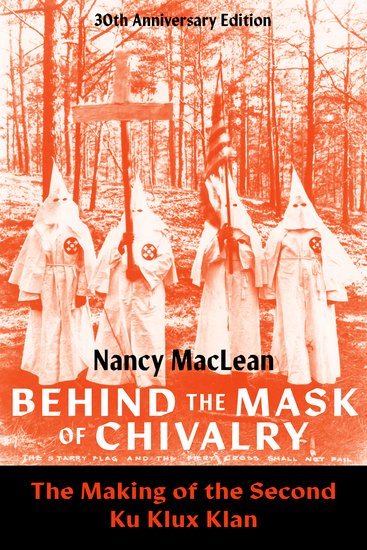

Formed in the Atlanta area in late 1915 under the leadership of Alabama-born former Methodist preacher William Simmons, the second Klan, inspired by the initial iteration of the post–Civil War Klan that officially went away in the wake of federal prosecutions in the early 1870s, achieved national influence in the post–World War I years. Every state in the union had Klan chapters by 1924. Growth was especially impressive in both Southern states like Alabama, Oklahoma, and Texas and Northern and Western ones like Indiana, Ohio, and Oregon. Members wore regalia, held weekly meetings, won positions in local, state, and national governments, organized marches in numerous downtowns, burned crosses in parks and on hilltops, and, most dreadfully, kidnapped, whipped, and sometimes tarred and feathered a diversity of victims.