To quote U.S. News: “At a time when Americans are awash in worry over the plight of racial minorities, one such minority, the nation’s 300,000 Chinese Americans, is winning wealth and respect by dint of its own hard work … Still being taught in Chinatown is the old idea that people should depend on their own efforts—not a welfare check—in order to reach America’s ‘Promised Land.’”

The subtext of such articles—“If Asian Americans are ‘making it’ in this country, why can’t Blacks?”—is a false equivalency, claiming that the discrimination Asian Americans faced was identical to that of slavery, segregation, and police brutality.

In The Souls of Black Folk—a pioneering work of sociology and African-American literature first published in 1903—W.E.B. Du Bois famously asks, “How does it feel to be a problem?” That is to say, African Americans have their bodies, their children, and their people maligned—their very existence a difficulty that needs solving.

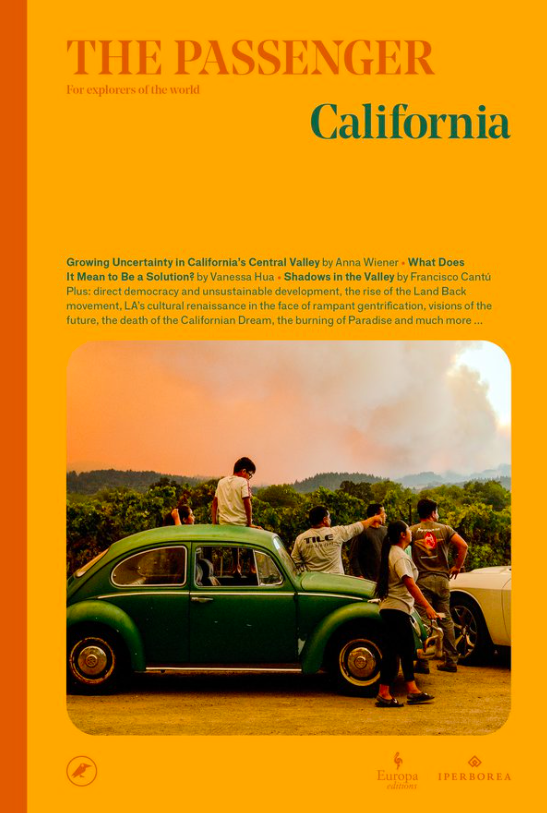

For Asian Americans, we might reverse the question and ask, “How does it feel to be a solution?” That is to say, to have their bodies, their children, and their people exemplified? This sudden embrace and elevation of Asian Americans as model minorities is suspicious, given America’s long history of xenophobia against them.

In 1849, the discovery of gold in California drew fortune seekers from around the world, and many Chinese people escaped economic chaos in their homeland. In the years that followed, politicians, unions, and businesses condemned the Chinese for taking away jobs and driving down wages of American workers.

By 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred Chinese laborers from coming to this country. For the first time, the US stopped being a nation that welcomed foreigners without restrictions and began to exert controls at the border and within the country—based on race, class, and gender. The first immigration law in the United States was designed to keep out Chinese. They were viewed as un-American, perpetual foreigners whose loyalties lay elsewhere, who didn’t belong among whites or Blacks. There were limited loopholes, allowing merchants and scholars and a few others to come in, but immigration from China plummeted for decades. More laws followed against migrants from other parts of Asia.

Congress repealed the Exclusion Act in 1943 when China became an ally of the United States during the Second World War. Yet policies, on the whole, all but banned most immigration from Asia. It wasn’t until 1965 that new laws were passed designed to attract skilled professionals, scientists, and engineers to the United States.