The first Death Wish is an odd film, one of a number of films that reflected the United States’ rough political transition from a period of gains on the political left starting in the post-WWII era, culminating in the radical demands for change and countercultural turmoil of the 1960s and early 1970s, through the political malaise and stagnation of the mid-to-late 1970s, to the right-wing Reagan Revolution of the 1980s. In certain scenes, Death Wish actually signals a surprising awareness of how readily smug left-liberalism, entrenched in its societal gains and cultural mores but cut off from any socialist principles or serious critique of the political status quo, swings rightward under pressure toward fascism, expressed as violent, generally racist fantasies of “cleansing” a corrupt population by force.

There’s good reason not to remember the film’s more compelling ambiguities, since its other lurid elements — such as manifest hatred of the poor and racist dog whistles — draw all the attention.

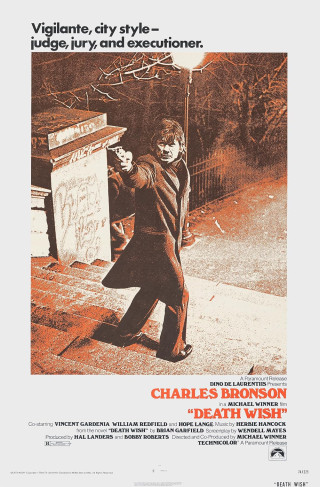

It’s the story of how mild-mannered architect Paul Kersey (Charles Bronson) goes from being a “bleeding-heart liberal” to a crazy-eyed vigilante after his family is brutalized by thugs. His wife Joanna (Hope Lange) dies as a result of the attack, and his daughter Carol (Kathleen Tolan) is gang-raped and so traumatized she has to be institutionalized. Soon afterward, Kersey is using the nighttime urban scene in New York City as a hunting ground, tracking malefactors, mainly unwary muggers, whom he shoots to kill.

Several of the would-be robbers Kersey shoots are black. But regardless of race, they all approach him in states of excessive, sneering villainy and unambiguous threat, generally pulling out knives and waving them in his face. There’s no indication, through editing or cinematography, that this is the subjective vision of Kersey, deranged by the horror of his family’s experience. It’s clear that these are essentially bad people acting out of evil impulses because they enjoy it, not because they might desperately need the money they always demand with demeaning curses.

The three men who commit the home invasion are white (startlingly, one of them is portrayed by the very young and still unknown Jeff Goldblum), but they’re the most cartoonishly villainous of all, exuding a kind of giggling depravity and love of violent chaos that ignites the protagonist’s determination that such people be put down like rabid dogs for the good of society.