Laura Ingalls Wilder, who wrote the “Little House on the Prairie” books, lived a good two decades of her 90 years in a covered wagon going west. Only in late middle age did she become the author of the most successful series for children ever written about the settling of the American frontier. In the stories these books tell, the Ingalls family embodies that extraordinary hunger for pioneering that, through the second half of the nineteenth century, sent a few million men, women, and children out into the prairies and mountains of the mid- and far West to farm, raise cattle, mine for silver, pan for gold. One and all, they went in search of a life free from the restraints of the socialized world, to a place where survival depended on the exercise of one’s own wit and strength and backbreaking labor.

Ultimately, that same drive to be alone with the wilderness got converted to a founding myth of individualism, out of which emerged an ideology that visualized freedom from government as an equivalent of freedom itself. The descendants of that myth are among us still. If Laura Ingalls Wilder were alive today she would be a member of the Tea Party. She would almost certainly have voted for Donald Trump, many of whose followers yet believe that he will restore to them the dubious glory of the frontier America that Wilder so passionately celebrated in her books.

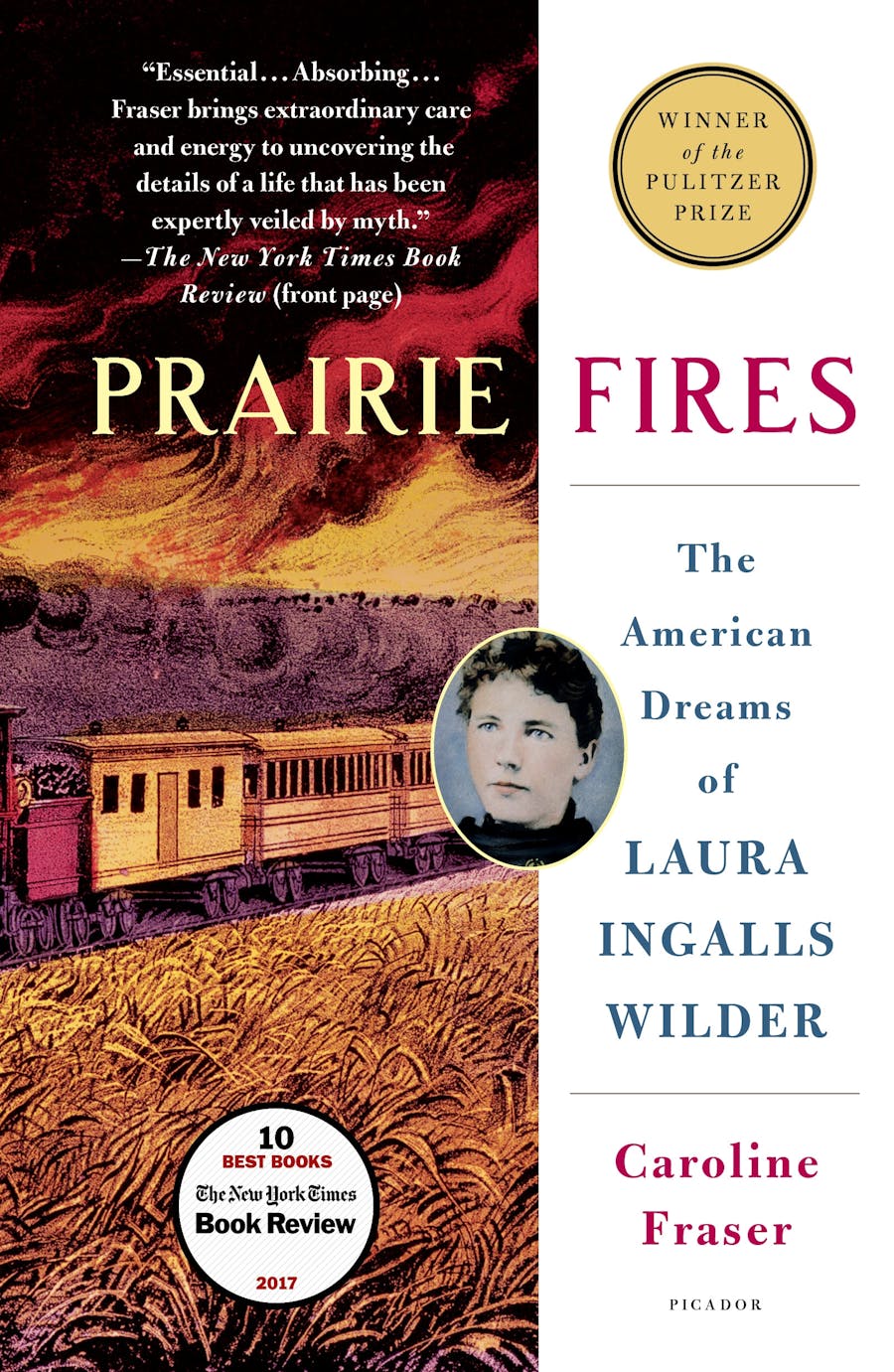

Caroline Fraser’s Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder is an impressive piece of social history that uses the events of Wilder’s life to track, socially and politically, the development of the American continent and its people. The frontier, by definition, has always been a place just beyond the point where land meets sky. In America that longing to move beyond the horizon, which is common to all cultures, became not only synonymous with an idea of the national character, but a vital ingredient in the American brand of democracy. The historian Frederick Jackson Turner ardently believed, in fact, that “that restless, nervous energy, that dominant individualism” attributed to the frontier was the major influence on American democracy’s development.

What the people in the covered wagons did not grasp was that to a large extent they were pawns in the hands of political and business interests—especially those of the railroads—that needed to see ground broken across the entire continent. The pioneers never understood the hucksterism behind the “go west, young man” rhetoric that urged them to go where none had gone before, with no hard knowledge of what actually lay before them. All the pioneers knew—in their fantasies, that is—was that just over the horizon lay adventure, opportunity, possible wealth, and certain freedom.