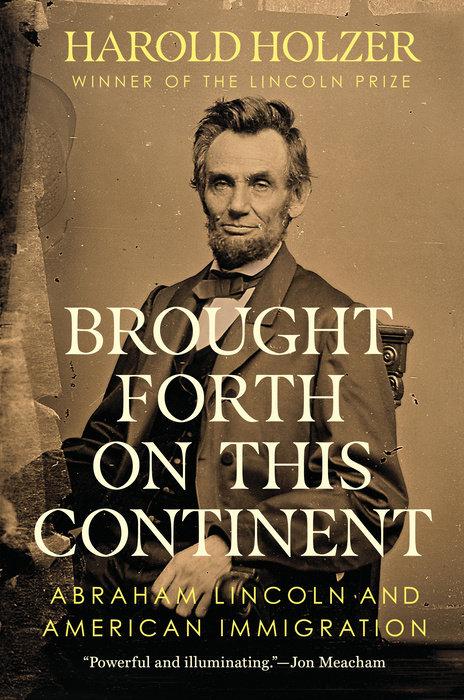

Throughout his early career, Abraham Lincoln worked not only as a lawyer and politician but also unofficially as a freelance journalist advocating for the Whig Party. For years, he contributed pseudonymous, sharp-elbowed columns to the Sangamo Journal, the Whig-affiliated organ for which he became an official “agent” while still living in New Salem, Illinois. That alliance broadened when Lincoln relocated to Springfield. Occasionally, Lincoln’s contributions proved combative enough to set off political fireworks.

One example that got dangerously out of hand ensnared Irish-born Illinois Democrat James Shields and Journal editor Simeon Francis, along with an unexpected participant: Lincoln’s former fiancée, Mary Todd. At the time, their on-again, off-again courtship was on again. Previously engaged to wed, the couple had broken off their relationship on January 1, 1841 — Lincoln might even have left Mary at the altar. Now, after a year of painful separation, they had reconciled.

In more ways than one, the local Whig paper brought them back together. When the couple resumed their friendship in 1842, Mary’s sister, still smarting from the aborted wedding she had been set to host, refused to welcome Lincoln back to her home. So Journal editor Francis and his wife made their Springfield parlor available for the rekindled courtship. It was here that Abraham and Mary, who shared a love for reading, likely devised a scheme to compose a series of satires aimed principally at Shields, who served as the Illinois state auditor. These became known as the “Rebecca” letters, and all of them appeared in the Sangamo Journal.

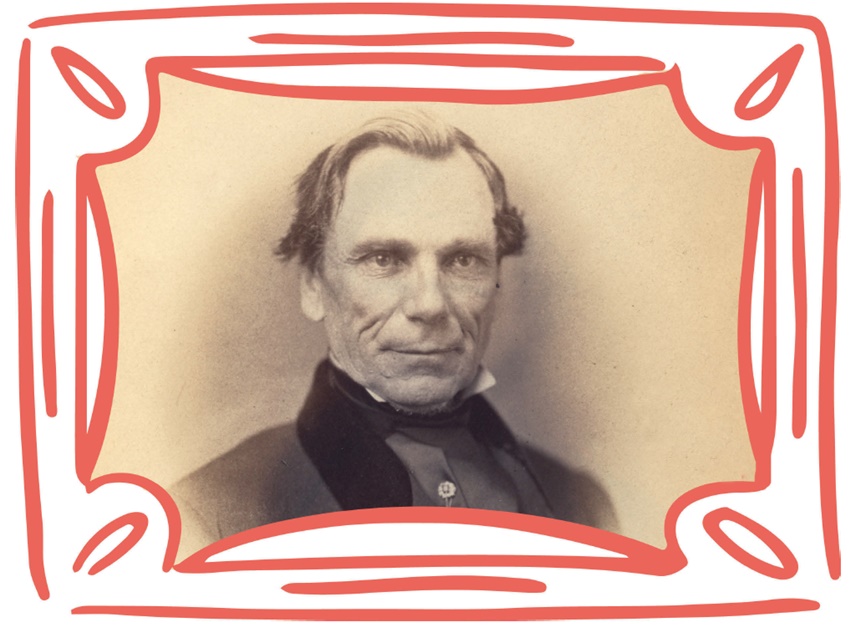

Shields made for a mouthwatering target. Born in 1806 in County Tyrone, Ireland, he had immigrated to Canada at the age of 20, later settling in Kaskaskia, Illinois, where, like Lincoln, he studied law, fought in an Indian war, and won a seat in the state assembly. There the similarities ended. As a Democrat, Shields opposed all the pet Whig initiatives dear to Lincoln. In society, Shields perceived himself as a ladies’ man — “a great beau,” in the words of a contemporary — though he stood but 5 feet 9 inches and probably spoke with a brogue. Lincoln, by now a master of irreverent stories and foreign accents, no doubt enjoyed telling jokes at Shields’s expense — and behind his back — replete with mimicry. That Mary herself was partly of Irish stock did not seem to inhibit her own eagerness to join in the mockery.