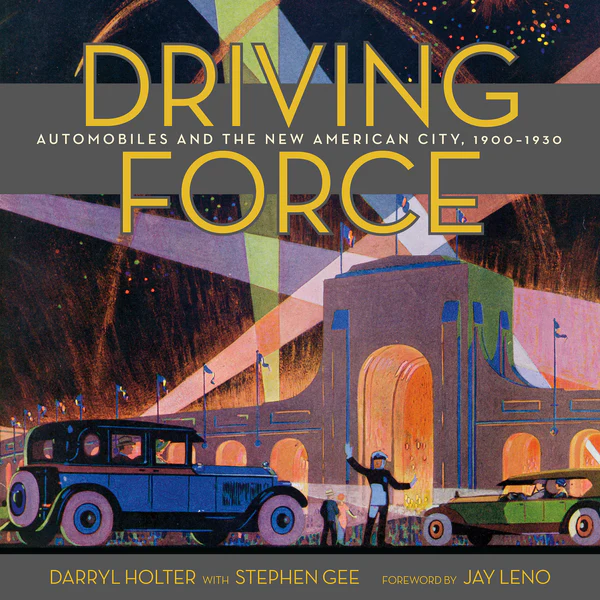

WE ARE ACCUSTOMED to thinking of the car as an inevitable fit for America and Americans when it appeared around 1900. A spread-out people, already accustomed to personal travel by horse, with an often-noted aversion to crowds, made the conversion to mechanical automobility easy. Nowhere was this more evident than in the region of Southern California. In 1900, Los Angeles was a new city, free from the density and labyrinthine streets of the old walking towns of Europe or even New England; it had attracted settlers (and developers) expecting personal space but also the easy access to work and shopping the car alone could provide. The city had weather that accommodated early roofless and unheated vehicles that in New York might have needed to be stored during winter. Even the early L.A. trolly system paved the way for the car by fostering dispersal and the subsequent need to fill in the gaps between the web of trolly lines with cars and roads. But, as Darryl Holter and Stephen Gee’s recently released book Driving Force: Automobiles and the New American City, 1900–1930 claims, Los Angeles as the United States’ quintessential car town cannot be reduced to such abstractions. People, even individualistic people, made it happen.

Most books about the people in this field have focused on heroic inventors and manufacturers like Henry Ford and Alfred P. Sloan, or the workers in automotive factories and their union led by Walter Reuther, or even promoters of highway and freeway construction like Robert Moses in New York. Interestingly, these figures came from—and gained fame from—their activities in the East. This seems odd, given the size and impact of cars on the West, especially Los Angeles. Even odder, this attention to manufacturing and infrastructure ignores a most vital fact: at the beginning of the car industry, Americans had to be won over to cars. In retrospect, this seems obvious, but it was not so in 1900. Not just cars but a vast array of new consumer goods that were mass-produced had to be sold to a sometimes reluctant populace. Advertising and new labeling may have impelled American men to buy Gillette razor blades and mothers to purchase Jell-O, but cars were different. They were complex, often unreliable, and, most of all, expensive machines (costing in 1900 about twice as much as the average yearly wage). Crucially, they demanded skilled operators on poor and often dangerous roads.