On January 12th, 1971, American television changed forever. A new sitcom on CBS was set to premiere, and the industry was at a fever pitch. The new project from television producer and writer Norman Lear would be the first of its kind, but few knew exactly how, or why. Despite the confidence CBS had in Lear and his program, the network was so nervous about its reception that it composed a disclaimer that audiences read moments before the show’s premiere. This was the first time that such a disclaimer had accompanied the debut of a primetime network sitcom, and for good reason. Lear’s main character was a self-identified bigot. The show appeared to be a powder keg waiting to happen, and Lear was about to light the fuse. CBS even hired additional switchboard operators to take the enraged phone calls executives assumed were coming.

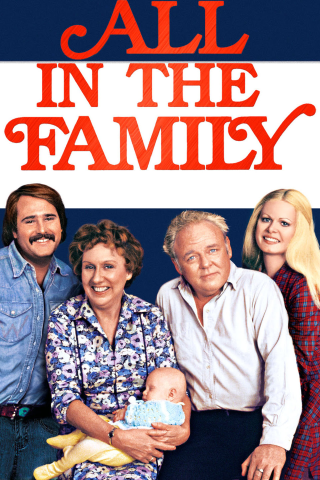

That night, Americans the country over were greeted with the following message: “The program you are about to see is All in the Family. It seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.” Lear and his writers sought a particular angle on the social issues of the times. Unlike many sitcoms before it, All in the Family would be inspired by contemporaneous events pulled from newspaper and magazine headlines, including the women’s rights movement and the Vietnam War. These events resulted in episodes such as “Gloria Discovers Women’s Lib” and “The Draft Dodger.” The Bunker family was loud and abrasive, but their family arguments about hot-button issues served two interrelated but different purposes: they entertained, and they encouraged self-examination. While the show wasn’t overtly religious, its approach to satire and social change still outlined the contours of Lear’s own religious liberalism. As we celebrate 50 years since the show’s debut, it’s worth looking back at not only its popularity and groundbreaking content, but also its religious legacy.

A program is often deemed “religious” if it has recognizable features of a familiar American religion. When it comes to something like All in the Family, religious legacy has less to do with specific characters, and more to do with the design of the show and the sitcom episodes themselves. In other words, All in the Family does not draw scholastic attention because of all of the “religious content” in the show, per say, but rather from the didactic and civic purposes it played in American public life in the 1970s. For Lear, making relevant television episodes by bringing attention to prejudice and social concerns reflected a broader assumption about liberal religious activism itself: to foreground questions of ethics and social improvement as the bases of spiritual praxis.