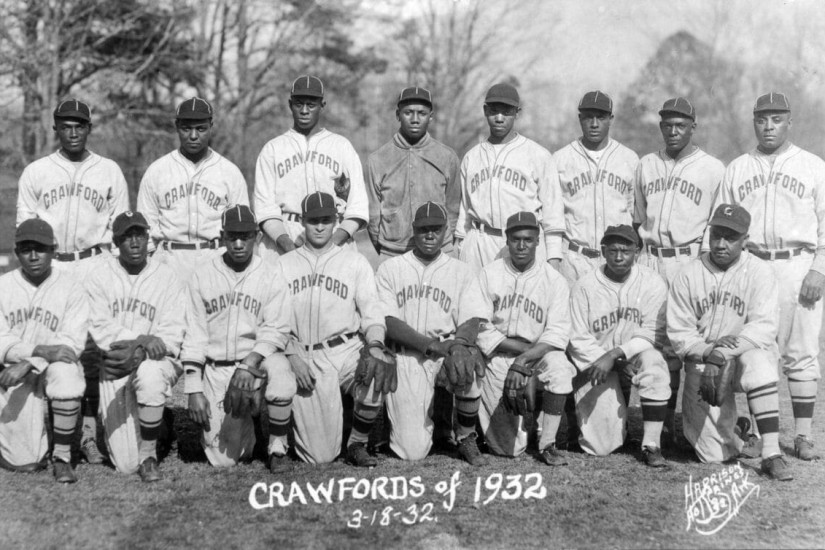

Josh Gibson recently made headlines, more than 50 years after his induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. On May 29, 2024, Major League Baseball (MLB) announced that Negro Leagues players’ statistics would be incorporated into its record books. Gibson, the star catcher for the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords in the 1930s and ’40s, has been placed atop several all-time leaderboards, including highest career batting average, slugging percentage, and on-base plus slugging (OPS). Gibson’s appearance in the major league record books was a long time coming, and it reflects wider recognition of the Negro Leagues and the evolution of research in baseball history.

Whether it’s historically or this morning, statistics matter in baseball. For fans and players, records—especially longstanding and iconic ones—matter in very special ways. Changes that placed Gibson back in the news are part of an ongoing reckoning with the racial segregation of professional baseball in the United States. Much has changed in the record books for major league baseball over the past several years. Gibson displaced Ty Cobb atop the lifetime batting average rankings. Other Negro Leaguers appeared in the top 10 in different statistical categories. Yet, the changes have had its dissenters, as a sector within the baseball community cried foul. Some critics think these stats are legitimate but not comparable. Would Negro Leaguers with 2,500 at-bats or 1,000 innings pitched sustain elite level of performance through 10,000 at-bats or 3,000 innings? Size of data sets is one thing; quality of play is a different can of worms. Dissenters, however, typically have not kept up-to-date with the tremendous research that has occurred over the past three decades, documenting and historicizing Black baseball broadly and the Negro Leagues specifically.

Historical significance has long been attached to baseball stats, illustrating how stats matter beyond the numbers. Henry Chadwick, credited with creating baseball’s original box score, viewed stats as providing accountability of performance. Stats became the basis of assessment of a player’s contribution and worth. So the range of reactions when baseball records are threatened and ultimately surpassed reveals a lot about the sports followers and US society.

The response to Gibson’s displacement of Cobb and others in the record book is but a recent example of the reverence given to achievement of white heroes of MLB’s segregated past. Babe Ruth’s 714 career home runs stood as an MLB record for 39 years. When Hank Aaron, a product of the Negro Leagues, was set to surpass Ruth as MLB’s home run king in the early 1970s, he received postal bags full of hate mail, including death threats. Some implored Aaron to retire and leave Ruth atop baseball’s home run list. Aaron persisted and overtook Ruth, an accomplishment that signified more than the changing of the record book. His achievement reflected how much the national pastime had changed with racial integration and the inclusion of African Americans and Afro-Latinos. Some fans celebrated his feat, while others’ reactions demonstrated resistance to the transformation of America’s game, in its participants and in its record books.

That transformation hasn’t slowed, and Gibson’s appearance atop MLB leaderboards captures a few significant changes in baseball history. First, it signals a reckoning with baseball’s segregated past. Recognition of elite Negro Leagues being on par with the American and National Leagues that composed MLB took decades. The Negro Leagues were maligned in mainstream newspapers, sporting periodicals, and most books on professional baseball well into the 1970s. Second, it reflects the invaluable research undertaken by Black baseball historians that produced a historical narrative that countered much of what was believed about Black baseball: its supposed lack of records, level of player talent, and importance to African American communities. Collectively, Robert Peterson, John Holway, Jim Riley, and Larry Lester, among others, have documented multiple aspects of Black baseball that many Americans believed was unknowable. Finally, the ascent of Gibson and other Negro Leaguers into the all-time leaderboards disrupts what many baseball fans have held dearly for decades: reverence for the achievements of white superstars of the segregated American and National Leagues. Yet these men never had to compete with many of their most talented contemporaries.

Stars from MLB’s segregated era have enjoyed staying power in rankings of the sport’s all-time greats in ways that Negro Leaguers such as Gibson, Satchel Paige, or Oscar Charleston have not. Cobb, Ruth, Walter Johnson, Christy Mathewson, and Honus Wagner continue to populate lists of all-time greats produced by modern baseball historians and sportswriters, even to the present day. The first class inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939, these men’s accomplishments in a white segregated institution (MLB) came with benefits: their statistics were knowable, recorded in daily newspapers, revered in the writings of journalists and historians, and held as truly significant by many baseball fans. Those who performed on the other side of baseball’s color line were viewed as unfortunate, forced to play in less certain conditions and their accomplishments deemed as less knowable. Recovering that history became the work of Black baseball historians who documented and historicized a circuit largely ignored by the US mainstream print media.

Reactions to baseball’s changing record book and revision of its history remind me of the important contribution of Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s Silencing the Past, specifically his discussion of how societies embrace specific historical narratives in the moment(s) of retrospective significance. These narratives provide explanatory power to how many people desire to understand the past, what merits celebration, and what is deemed less significant and often silenced. For much of its afterlife, the Negro Leagues were deemed less significant than white MLB and became buried within narratives that celebrated MLB’s racial integration after 1947. Some did not forget. Black journalists including Wendell Smith, Sam Lacy, and Dan Burley continued to recount the feats of Black baseball greats and called for their recognition. Mainstream baseball writers and historians largely ignored their calls. Ted Williams pierced the silence within organized baseball circles in 1966 during his Hall of Fame acceptance speech, when he declared the honor of induction would have greater meaning when he would be joined by Gibson, Paige, and “the great Negro League players that are not given a chance.”

Williams’s words spurred action, and the Hall of Fame formed a special Negro League committee. Yet it was the work of historians to truly address the silence within historical narratives that had been produced about baseball, race, and the color line.

Negro League history is full of notable accomplishments from legendary players like Paige, Gibson, and James “Cool Papa” Bell. For countless baseball enthusiasts, Buck O’Neil served as their initial narrator of Black baseball history. In Ken Burns’s documentary Baseball, O’Neil’s riveting storytelling about Gibson’s hitting prowess, Paige’s pitching dominance and off-field antics, and Bell’s speed, among others, introduced viewers to a world hidden by those baseball writers and historians who had left Black baseball out of their accounts. O’Neil’s oral account complemented the work of Negro League historians. Originally published in 1970, Robert Peterson’s Only the Ball Was White provided the first thorough account of the flourishing of a Black baseball circuit. Peterson inspired a generation of historians who engaged in the work of examining physical copies and microfilm reels of Black newspapers. Black baseball historians also gathered oral interviews with surviving Negro League players, team officials, and owners that shed further light on the Black baseball circuit and its importance for African American communities. The works they produced changed the narrative, altered what we knew about baseball’s past, and challenged us to reconsider how we assessed integration.

Recapturing the stories of the Negro Leagues in narrative form and establishing the statistical record has required much labor. In 2006, MLB funded a study by the Negro League Research and Authors Group (NLRAG) led by Dick Clark, Larry Lester, and Larry Hogan; I was fortunate to be a participant in NLRAG’s work and a collaborating author. The research conducted over three years provided the foundation for the statistical records we now have of the Negro Leagues. Other baseball historians such as Gary Ashwill and Scott Simkus undertook additional research that further built the statistical database. It is due to the work of historians that we have access to and know more about Josh Gibson and Black baseball than ever before.

Whether the achievement of Negro Leaguers is fully embraced by fans and in broader society will further validate Trouillot’s argument about the moments of retrospective significance and about the power in the production of history. Will the final score show nostalgia or history triumphant in the acknowledgment of all-time greats in baseball?