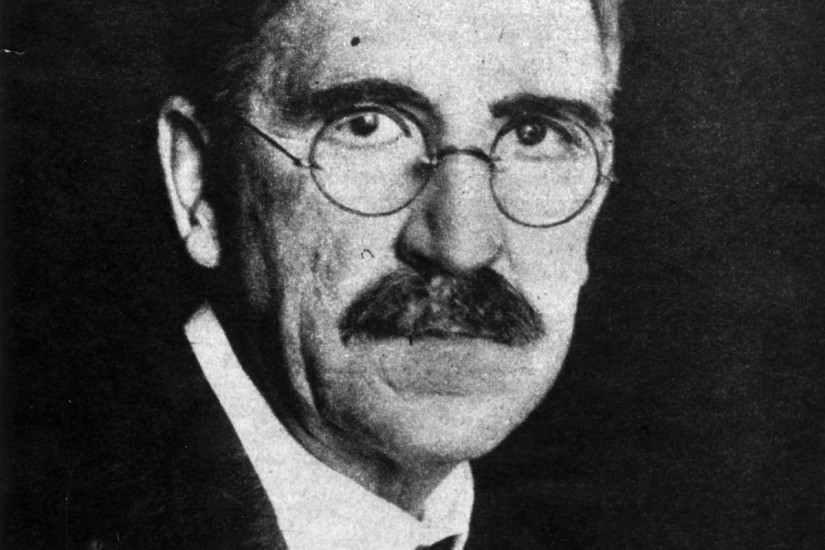

“If radicalism be defined as perception of need for radical change,” the American philosopher John Dewey wrote in his 1935 book Liberalism and Social Action, “then today any liberalism which is not also radicalism is irrelevant and doomed.”

Over the course of a lifetime that stretched from the Civil War to the Cold War, Dewey pushed liberal commitments to freedom of inquiry, equal opportunity, and personal liberty to their democratic limits. Realizing that equal liberty for all required democratizing institutions from the state to the workplace and the school, Dewey set his radical liberalism on a collision course with the capitalist social relations that liberalism historically served.

While the Vermont product became one of the twentieth century’s most well-known philosophers, widely considered the philosopher of American democracy itself, his idiosyncratic thought earned him enemies across the political spectrum. The Right saw him as a Communist, the Communist Party saw him as a philosopher of reaction. As for Dewey, the only “ism” he could attach his name to was “experimentalism.”

Dewey’s experimentalism, or “pragmatism” as he often called it, has long been viewed with suspicion by many leftists, who see its aversion to far-reaching theories as a precursor to Cold War liberalism’s proclamations of “the end of ideology.” Yet revisiting Dewey’s decades-long attempt to renovate liberalism from within reveals a more complicated story.

In radicalizing liberalism, Dewey ended up formulating a democratic socialism that strove to expand workers’ control over the social forces that shaped their lives. And that, he had no trouble admitting, required confronting capitalism.