“Slugs’ was a lowbrow joint, but it was also part of the youth movement,” the drummer Billy Hart told me. “Broadway people and fashion models mingled with college students and true jazz fans. There was sawdust on the floor, a big hole in the stage, and the club owners and the musicians who played there all chased the same models—or waitresses—and smoked the same pot.” What that assortment of listeners heard at Slugs’ was a community music, played by members of a close-knit New York circle who studied their craft together in the afternoon before playing at the club at night. But most of these musicians were originally from other cities. Among the musicians on Forces of Nature, Henderson is from Detroit, Tyner and Grimes are from Philadelphia, and DeJohnette is from Chicago. Each hometown boasted its own teachers and mentors, and just as important was the audience, made up of residents of working-class Black neighborhoods proud of their city’s young talent.

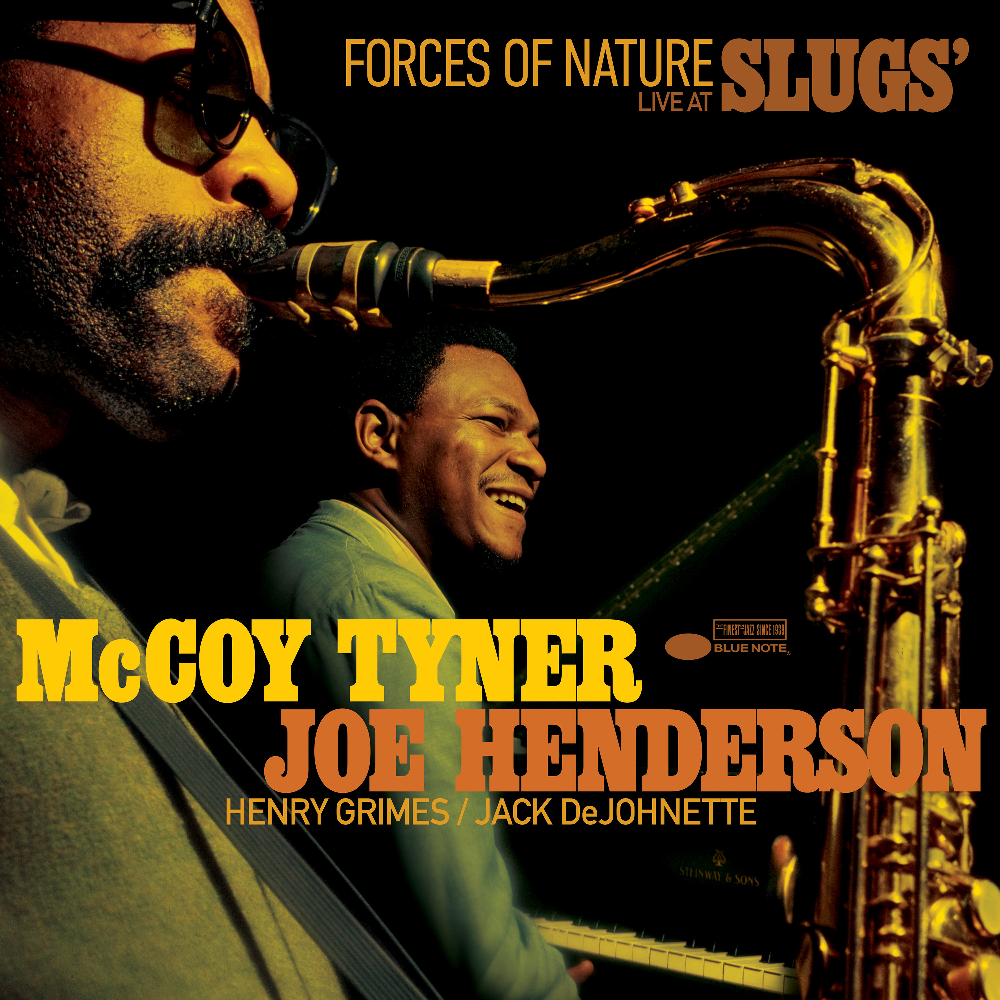

In the liner notes to Forces of Nature, Joshua Redman, an acclaimed tenor saxophonist who emerged in the 1990s, unequivocally places Henderson in the jazz pantheon alongside Coltrane and Sonny Rollins. Henderson is not as well-known as those giants, but his influence is monumental. He commanded the whole spectrum of jazz, from bebop to the avant-garde, while still sounding like nobody else. His early compositions, like the now-standard pieces “Recorda Me” and “Inner Urge,” were essential in shaping the style of jazz that emerged during this era by pioneering new approaches to rhythm and harmony.

Those innovations were organic. Little of this music was made by musicians who learned about jazz at college. They learned about it from the streets, from the barbershop, from the high school dance. It was still a proudly Black music: Indeed, a growing political consciousness was an important factor in the sound of the era and can be traced in a series of album titles that sound progressively more militant. (Henderson started with Page One in 1963 and by 1971 was releasing In Pursuit of Blackness.) Still, Black musicians didn’t object to the participation of white musicians, like Chick Corea and Joe Farrell, if they had something special to offer.

Perhaps because of its lower visibility in the historical record, this style of 20th-century music has never really been given a name. “Modal jazz,” which means working with a scale or sequence of scales as opposed to conventional cycles of chords, is a contender, although there’s a lot more going on than that. The historical literature sometimes refers to “post-bop,” simply denoting the period after bebop and hard bop, but that’s almost pointlessly generic. Names are difficult: Many major practitioners don’t even like the words jazz and bebop. Tyner, the greatest modal pianist of all time, told Marian McPartland in a 1983 interview that he didn’t like the word modal.