When The Texas Chain Saw Massacre hit theater screens in October 1974, American viewers had endured a tumultuous number of years. Just a few short weeks before, Nixon had resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandal. The U.S. and other nations that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War faced retaliation from oil-producing Arab states in the form of a six-month embargo on oil exports, which threw the American economy into a spiral. That crisis sparked a recession, ending a decadeslong period of economic prosperity. U.S. troops returning from the ongoing war in Vietnam were facing hostility from their neighbors and indifference from their government. And the early stages of American deindustrialization were already underway: Jobs were starting to vanish.

Ted Bundy was killing young women in the Pacific Northwest at the rate of roughly one per month, and John Wayne Gacy was killing young men and boys in Chicago. Christine Chubbuck had recently died by suicide after shooting herself on live TV. Patty Hearst had been kidnapped by, and seemingly joined, the Symbionese Liberation Army. Violence was in the air. So was rampant pessimism and anger. A Gallup poll from October 1974 reported that 7 in 10 Americans “held little hope for any immediate improvements.”

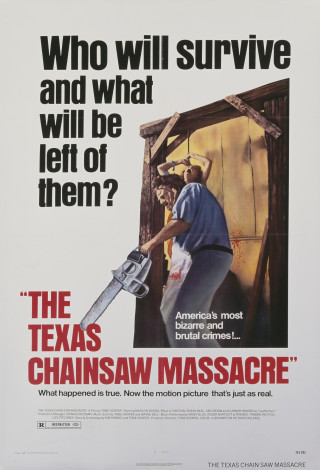

In the midst of all this, a movie about innocent people being killed indiscriminately with lumber machinery functioned as a kind of primal scream. The plot of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is about as straightforward as it gets: On a road trip through Texas, Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) and her hippie friends, stranded for lack of gas, are set upon by a family of killer cannibals, the Sawyers, who torment and kill them in a variety of grisly ways. Directed by Tobe Hooper, the gory exploitation flick became an instant classic of the horror genre.

But the reason The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, which has generated a whopping eight sequels and spin-off films, has lingered in our cultural consciousness for 50 years now has little to do with the mechanics of what happens on-screen. It sticks with us because of how vividly it captured the hysterical unreality of living in a turbulent age, and how it picked at the scabs crusting over the face of the American dream.