When Miles Davis first heard the music of Eric Dolphy, a key figure in the free jazz movement, he described it as “ridiculous”, “sad” and just plain “bad”. Upon encountering the early sounds of free jazz pioneer Ornette Coleman, Thelonious Monk said “there’s nothing beautiful in what he’s playing. He’s just playing loud and slurring the notes. Anybody can do that.” The editors at the jazz world’s bible, Downbeat Magazine, went further, initially criticising the entire genre as a force that’s “poisoning the minds of young players”, jazz critic Gary Giddins recalled.

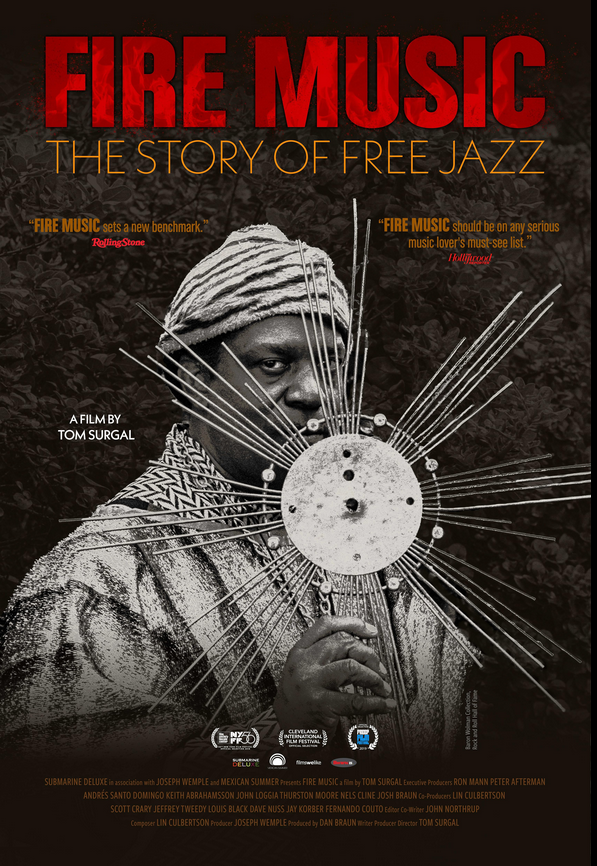

Given the revolutionary nature of the music, it’s no surprise that many in the field greeted it with such disdain. “Free jazz didn’t adhere to any of the rules of what was considered music at the time,” said Tom Surgal, director of the new documentary Fire Music, which covers the history and breadth of the movement. “There wasn’t a single musical tenet this music did not defy.”

That included everything from its approach to chords to the placement of the beat to the role of the solos to the basic notions of melody and harmony. Atonality and abrasion were embraced, polyrhythmic and polytonal modes were amplified and risk idealized, paving the way for some of the most extreme and, to some ears, difficult, music ever made. As even Surgal admits, “this is not easily digestible music”.

A foundational figure in the genre, Cecil Taylor, had a word of advice about that. “The same way that musicians have to prepare, listeners have to prepare,” he said in a vintage interview used in the film. But when the movement started in the late 50s and early 60s, few were in any way prepared. Bebop ruled jazz at the time, exemplified by well-established stars like Max Roach, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, each of whom presented then codified approaches to solos, rhythms and melody. As exciting, erudite and skilled as their work may have been, their approach had become familiar enough to spur artists like pianist Taylor and saxophonist Coleman to seek something new.

Taylor began to capture that on record with his 1956 debut, Jazz Advance, in which he displayed a highly percussive approach to his instrument, performing with equal degrees of energy and technique. The music created by his quartet expanded the use of improvisation, bringing a wildness to original pieces, as well as standards like Cole Porter’s You’d Be So Nice to Come Home To. On Taylor’s two albums released in 1960, Air and The World of Cecil Taylor, he pushed further, leaving more traces of bebop behind to play in a world of his own making.