During the high point of Hollywood’s studio era, when motion pictures made their storied transition from silents to talkies, no studio was more glamorous, more lavish, more star-studded than Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (“more stars than there are in heaven” was its apt motto). It boasted such directorial luminaries as King Vidor, Victor Fleming, George Cukor, and Ernst Lubitsch; its contract writers included Lenore Coffee, Donald Ogden Stewart, Dorothy Parker, and Anita Loos; and its roster of A-listers was seemingly endless—Clark Gable, John Barrymore, Jean Harlow, Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Judy Garland, and Fred Astaire were among its brightest talents.

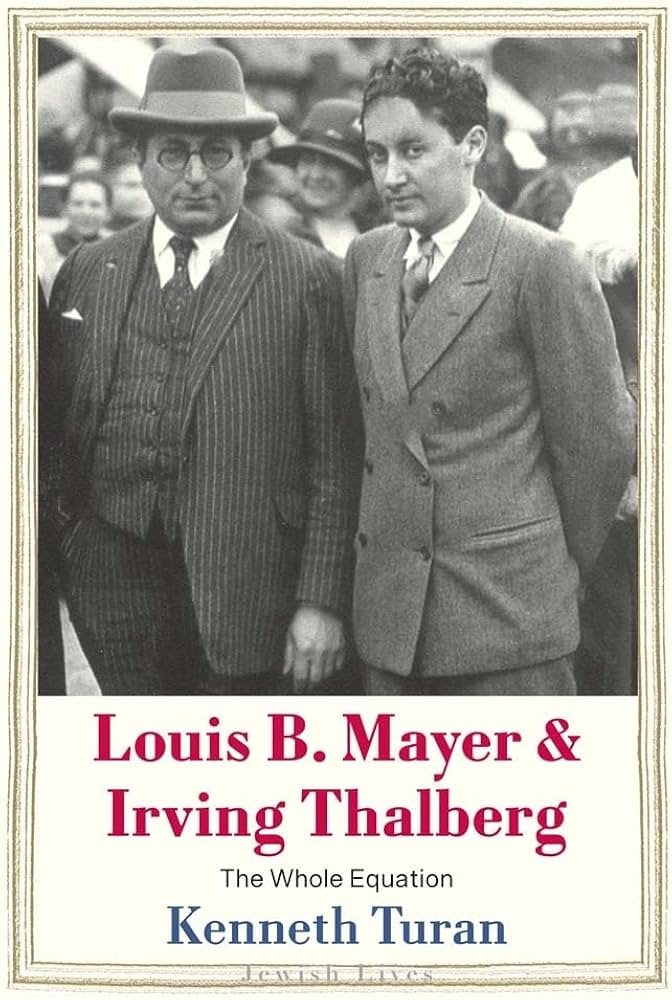

At the helm of it all were two powerful producers: the irascible, relentlessly driven studio patriarch, Louis B. Mayer; and the soft-spoken, considerably younger (yet equally ambitious) vice president and head of production, Irving Thalberg. They are the twin subjects of Los Angeles Times film critic emeritus Kenneth Turan’s engrossing new book, Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation. Turan takes his subtitle from a stray passage of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel The Last Tycoon, whose protagonist, the Thalberg-inspired ace studio executive Monroe Stahr, is said to be among the few men in Hollywood who “have ever been able to keep the whole equation of pictures in their heads.” Together, Mayer and Thalberg achieved spectacular commercial and critical success and, as Turan writes, turned MGM into “the standard by which others were judged.”

The two men came from dramatically different backgrounds. Mayer, who was given the name Lazarus at birth, was raised by impoverished East European Jewish immigrants in New Brunswick, Canada, where he left school at the age of 12 to help his father peddle scrap metal. With the money he earned in the family business, he moved to Boston and bought up old theaters, ultimately transitioning into film distribution and production and clawing his way into the picture business (then still in the age of nickelodeons). More than a dozen years later, Thalberg was born to German-Jewish stock in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn, not exactly well-to-do but on the rise. At birth, he was diagnosed with a congenital heart condition called methemoglobinemia (or “blue baby syndrome,” as it was known at the time) and given a predicted life span of 30 years. Bedridden for a stretch during his teens, Thalberg dropped out of high school and headed for Hollywood, where he had the good fortune of being made the personal assistant to Universal Studios boss Carl Laemmle, a German-Jewish émigré known to hire his own.