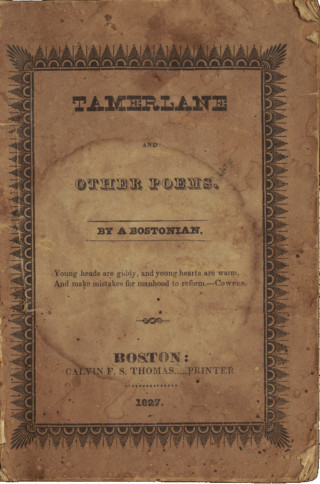

Both Poe and the novice printer Calvin F.W. Thomas were just eighteen when the poet handed over his manuscript, presumably at Thomas’s shop at 70 Washington Street in Boston, and paid him to make it into a book. The result was forty pages of unevenly printed verse bound in drab tan wrappers the shade of a faded tea stain. Tamerlane’s front cover features a potpourri of discordant typefaces within an ornamental frame that resembles a geometric queue of conifers—a heavy-handed period design I have grown to adore. It’s clear that Thomas, as a workaday job printer whose usual commissions were show bills, apothecary labels, calling cards, and the like, had his shop stocked with a mishmash of typefaces to fit any taste. On this occasion, he seems to have drawn liberally from his inventory.

While there’s no evidence to suggest the printer realized its significance before his death in 1876, his modest hand-sewn pamphlet marked the beginning of one of the most revolutionary, incandescent, and influential careers of any writer in his, or any, century. It is speculated that Calvin Thomas’s family were acquainted with Poe’s birth parents, Eliza and David, in Boston, and that the teenaged Poe knew of him that way. But Calvin’s business was included in the Boston Directory, so it’s every bit as likely he hired him through this listing.

The young poet, who’d left Richmond, Virginia, after dropping out of university when his foster father, John Allan, gave him insufficient funds to continue (Edgar had racked up gambling debts in a reckless attempt to make up the difference), may not have shared his identity with Thomas when the printer produced his “little volume” with its “many faults.” Indeed, Poe’s name is nowhere to be found in Tamerlane. Its authorial attribution is simply “By a Bostonian.” Its Preface, at once boastful and self-defensive and very Poean, is unsigned.

Inconspicuous, fragile, published sans fanfare, ignored by reviewers, its sales poor, had Tamerlane been Edgar Allan Poe’s only publication, a one-off chapbook of melancholy romantic verse, it would now be a mere bibliographical curiosity. A fugitive document of interest to some scholar of early Lord Byron imitators or a specialist—are there any?—of Boston job printers of the period.

Instead—because its author went on to invent the modern detective story (think “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” and “The Purloined Letter”), revolutionize the Gothic genre with tales like “The Cask of Amontillado” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” pen triumphs of supernatural horror like “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and write the classic macabre poem “The Raven,” which many of us tried to memorize as kids—Tamerlane, for its now-insignificant deficiencies as a poem and a pamphlet, is of towering importance to Poe specialists and aficionados alike.