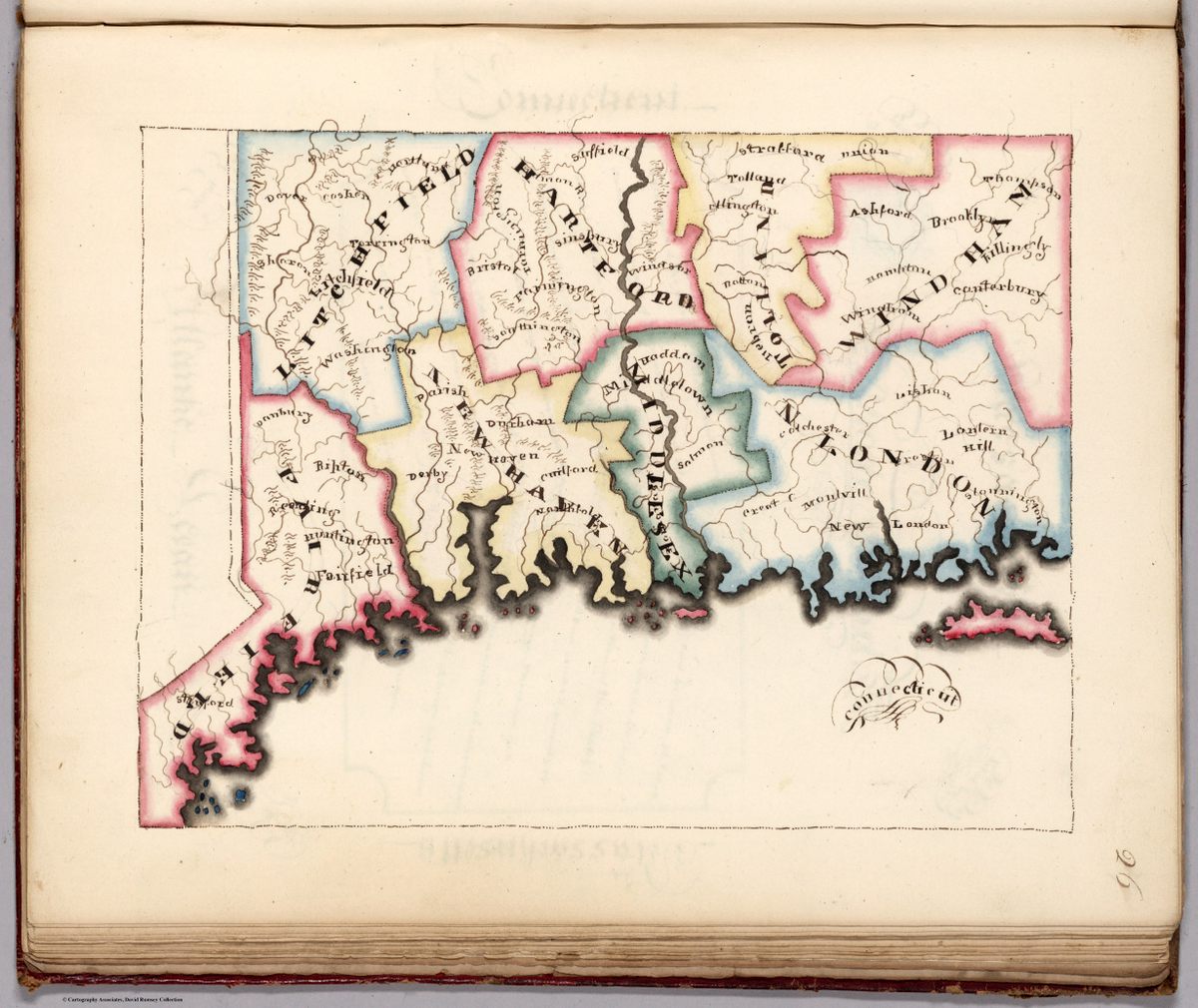

The first “schoolgirl map” that caught historian Susan Schulten’s attention was made in 1823 by Frances Henshaw, a student at one of the best schools for girls in the young United States. The map came from Henshaw’s Book of Penmanship, which included details about geography and astronomy—comets, meridians, horizons, polar circles, and climate zones. The young woman’s drawing encompassed 19 states, copied from Carey’s American Pocket Atlas, from 1805, and Arrowsmith and Lewis’ Atlas, from 1812.

Schulten studies 19th-century American cartography at the University of Denver, and she was excited to find a map so charming and pretty, with a connection to the history of education for women. The more she started looking for maps like it, the more she found, until she had collected around 150 maps made by American schoolchildren in the early 1800s. “I started looking at them because I was captivated,” she says. “They jump at you … someone put so much time into this.”

And soon she realized that these weren’t just lovely images. “I realized there were some patterns,” she says. “Once I started seeing patterns, I realized that this was a hidden part of American education that you wouldn’t know about if it weren’t for the maps.”

Before this time in American history, any education that girls received happened at home, through lessons from their families or, for the most well-off, with private tutors. But in the decades after the American Revolution, educators opened hundreds of small academies for young women. Each school had a curriculum tailored for girls, focused on subjects considered appropriate at the time. Geography was a safe subject, and one popular exercise had girls tracing or drawing maps.

The maps that Schulten was finding weren’t practical tools, though. Many lacked indications of scale, for instance. Instead, they showed off the mapmaker’s artistic skill and were opportunities to practice penmanship. The names of cities, rivers, and states, for example, might all be done in different lettering styles. Some students took up the task of making detailed maps—which could be tedious and downright boring—as exercises in mental discipline. Some of the most influential educators at the time, including Emma Willard, a pioneer in education for women and another subject of Schulten’s work, saw maps as powerful tools to aid memorization and analysis.

One of the more fascinating aspects of these maps—made mostly by young women, but occasionally by young men—is how they reflect a growing sense of American identity. Often students created maps of the entire globe or of their home states, but after the War of 1812, which the United States saw as a victory, there was a spike in maps of the country, Schulten found.