One reason Oppenheimer and his collaborators are so indelibly associated with the bomb is surely the weapon’s terrifying power. Another is early press coverage: William Laurence, a science reporter for the New York Times who witnessed the Trinity test, placed great emphasis on the roles of Oppenheimer, Teller, and other physicists in articles published in late 1945. Similarly, the Smyth Report, the first public governmental account of the Manhattan Project, described the physics and physicists in detail while playing down the contributions made by chemists, engineers, metallurgists, and others.

But those factors still don’t fully explain the fascination with Oppenheimer. A crucial reason why he remains so alluring is more intangible. It relates to the belief that as highly educated intellectuals, scientists are inherently morally upstanding. Despite plagiarism scandals, the #MeToo movement, and countless tales of bad behavior, scientists are still often assumed to be in the moral elite. And in the immediate postwar period, at a time of widespread trust in authority and government—before the Watergate scandal and the rise of the environmentalist movement—that association was even stronger.

If one believes that scientists are honorable paladins, then it’s jarring to think that members of that select group were the ones who developed a weapon that killed at minimum 110 000 people (a likely biased estimate) and injured thousands of others while being used only twice. Perhaps the reason why the physicists of the Manhattan Project occupy prime real estate in historical memory is because the dichotomy between their supposed moral uprightness and the images from Hiroshima stuck in the collective consciousness. That would jibe with another instance in which arms designers have found a place in historical memory: the development of chemical weapons during World War I by researchers including Fritz Haber. In both examples, the creation of weapons that would inflict horrifying suffering was championed by supposedly morally upright scientists.

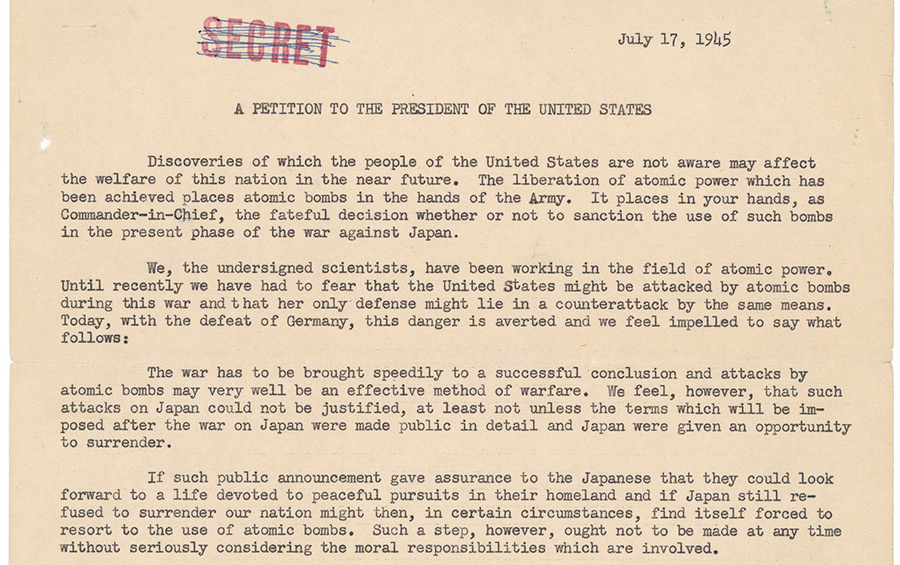

Unlike Haber, who never expressed remorse for his work on chemical weapons, many of the Manhattan Project scientists seemed to be ambivalent about their creation. Think of the quotation from the Bhagavad Gita that Oppenheimer claimed had popped into his head at the Trinity test: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.” Although we’ll never know if Oppenheimer actually thought that at the time, the quote has become part of the lore of the bomb. It’s often paired with a more profane quotation from Kenneth Bainbridge, who stated to Oppenheimer after the explosion, “Now we are all sons of bitches.”