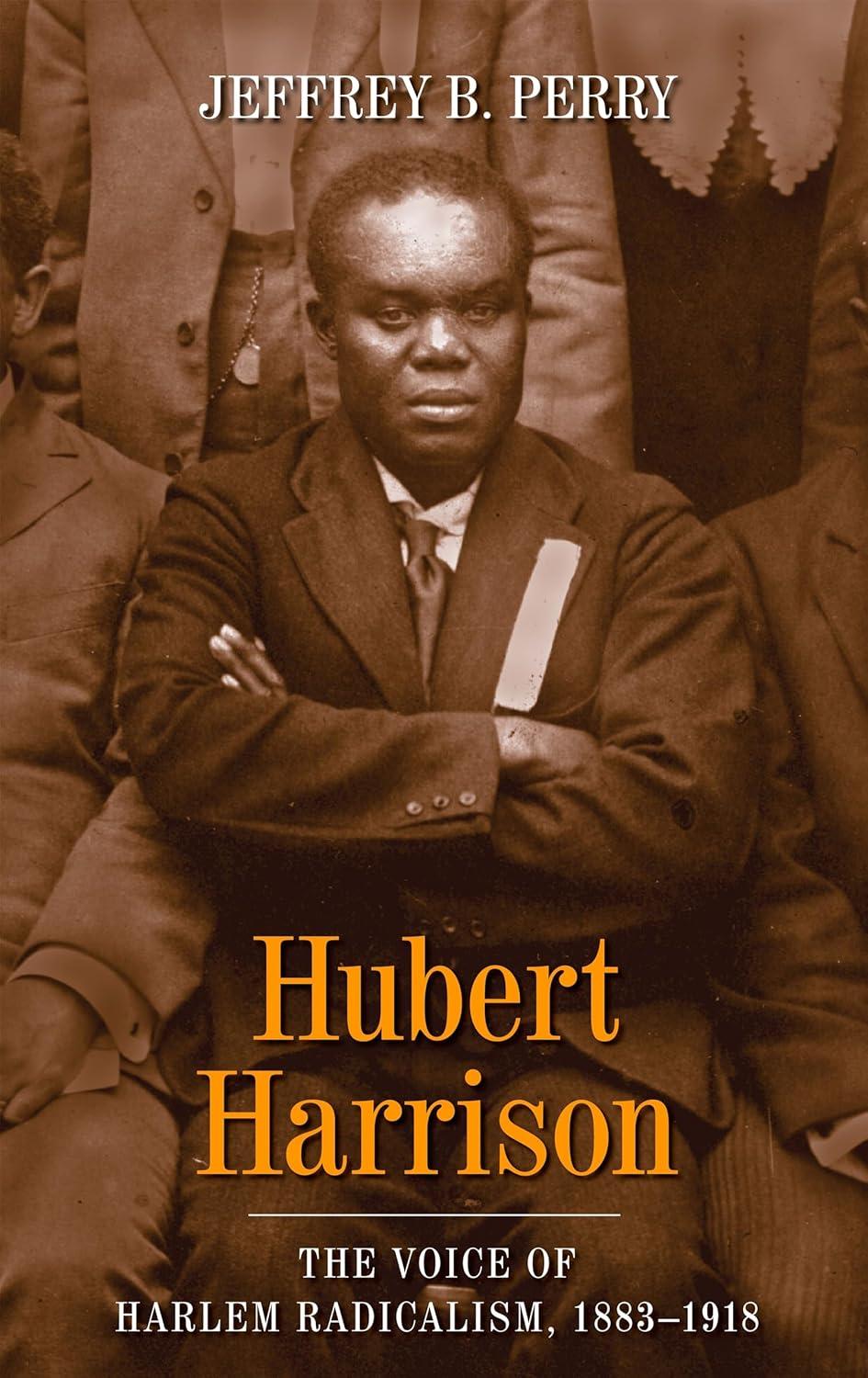

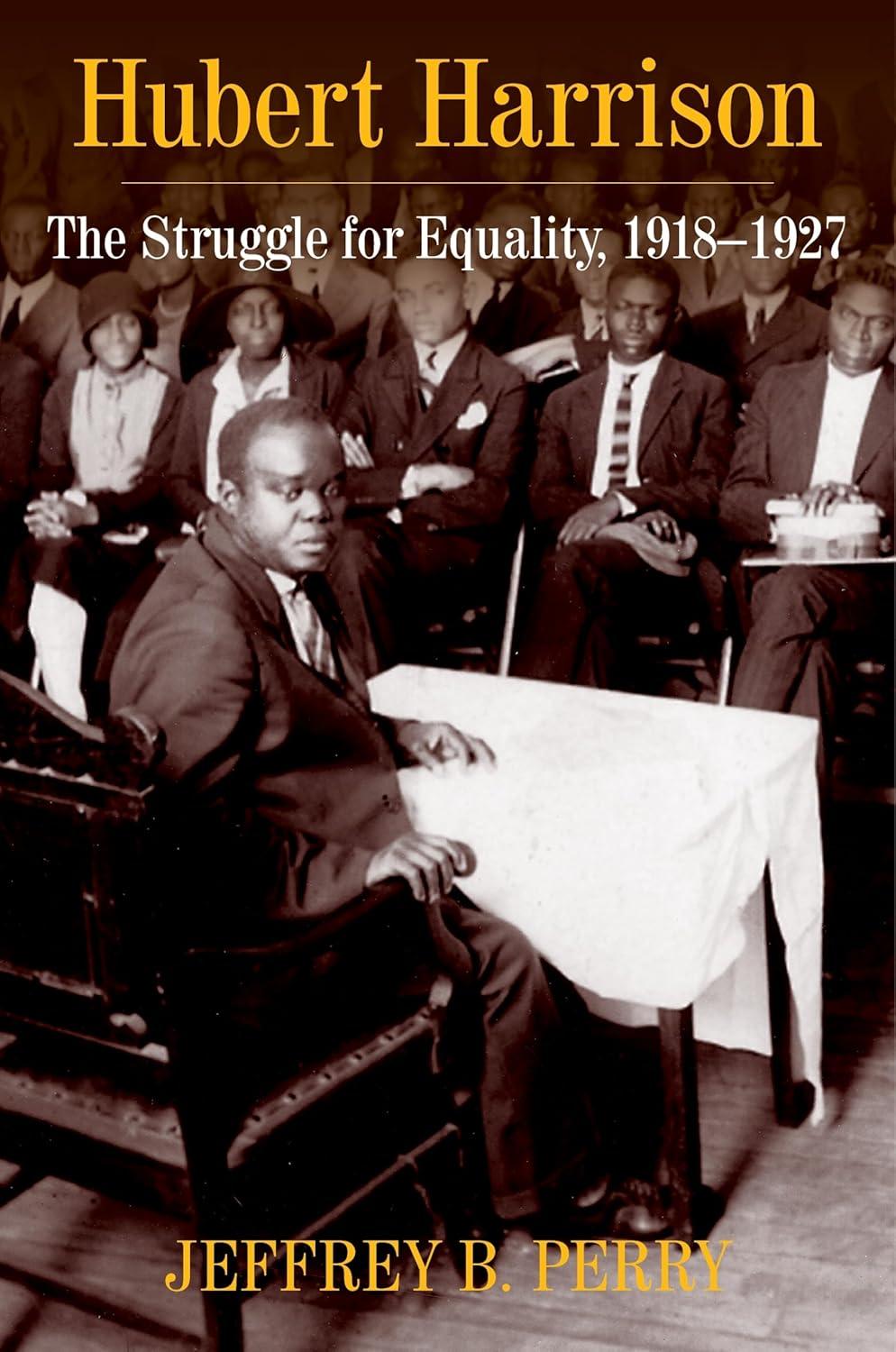

A recent two-volume biography by Jeffrey B. Perry—Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883–1918 and Hubert Harrison: The Struggle for Equality, 1918–1927—seeks to correct this oversight. Tracking Harrison’s life from his birth in the Danish West Indies to his long career as an activist and intellectual in Harlem, Perry leaves no stone unturned in understanding the man, the times in which he lived, and the ideals he championed. Harrison’s intellect was matched only by his steadfast refusal to bend on his principles—including not taking money from sources he disagreed with. A biography that is also a work of intellectual and institutional history, Perry’s two volumes offer an incisive survey of the radical upheaval at the turn of the 20th century. But above all they make a case for why Harrison is a crucial part of the American radical tradition.

Perry’s background as a working-class intellectual—not to mention his writings on race and labor in American life—make him the perfect person to help recover one of the early 20th century’s great Black intellectuals and socialists. Having written for publications like Black Agenda Report, CounterPunch, and many others, Perry has spent years arguing for the importance of understanding how race and class are bound together as categories used to stratify and divide American society. For Perry, what defined Harrison’s legacy as a radical was that he avowed a socialist and class-based politics and yet also refused to abandon the masses of Black Americans, north and south, in their struggle against racism. Instead, Harrison examined the problem of race and class and came to the inescapable conclusion that only mass politics and organizing among Black Americans could free them and, by extension, the working class from future exploitation.

Indeed, the story Perry presents revises what most curious readers know about the history of US radicalism in the early 20th century. Harrison played a key role in two important radical traditions at once: the Black freedom movement and the building of a Socialist Party in the United States. While many histories of the era treat the two as separate, Perry’s biography shows that for Harrison, socialism and Black radicalism were inextricably linked, motivated by the same insights and commitments; there was no way to privilege one over the other. As Perry argues in the first volume, Harrison was “the most class conscious of the race radicals, and the most race conscious of the class radicals.”