To measure the impact that slavery has had upon modern life, historians turn tragedy into evidence: We count the number of bodies thrown overboard from a slave ship; the number of bodies hanging from trees in Indiana; and the 5.4 million dead as a result of wars in Congo since 1998 over access to minerals needed to manufacture cell phones and video games. We analyze the death rates of Indigenous communities exacerbated by European arrivals, death rates in the Middle Passage, and population counts of enslaved laborers in the American South or the Caribbean. We do so because, in part, we know that to be modern is to have a rational relationship to information that we are able and willing to quantify accurately and honestly. But quantifiable data can only be part of the path to knowledge, to comprehending the impact of what we study. When we aggregate, we lose the specificity of each life lost to war or disease or the ravages of a changed climate. We lose the understanding of the pain of addiction, despair, and loneliness.

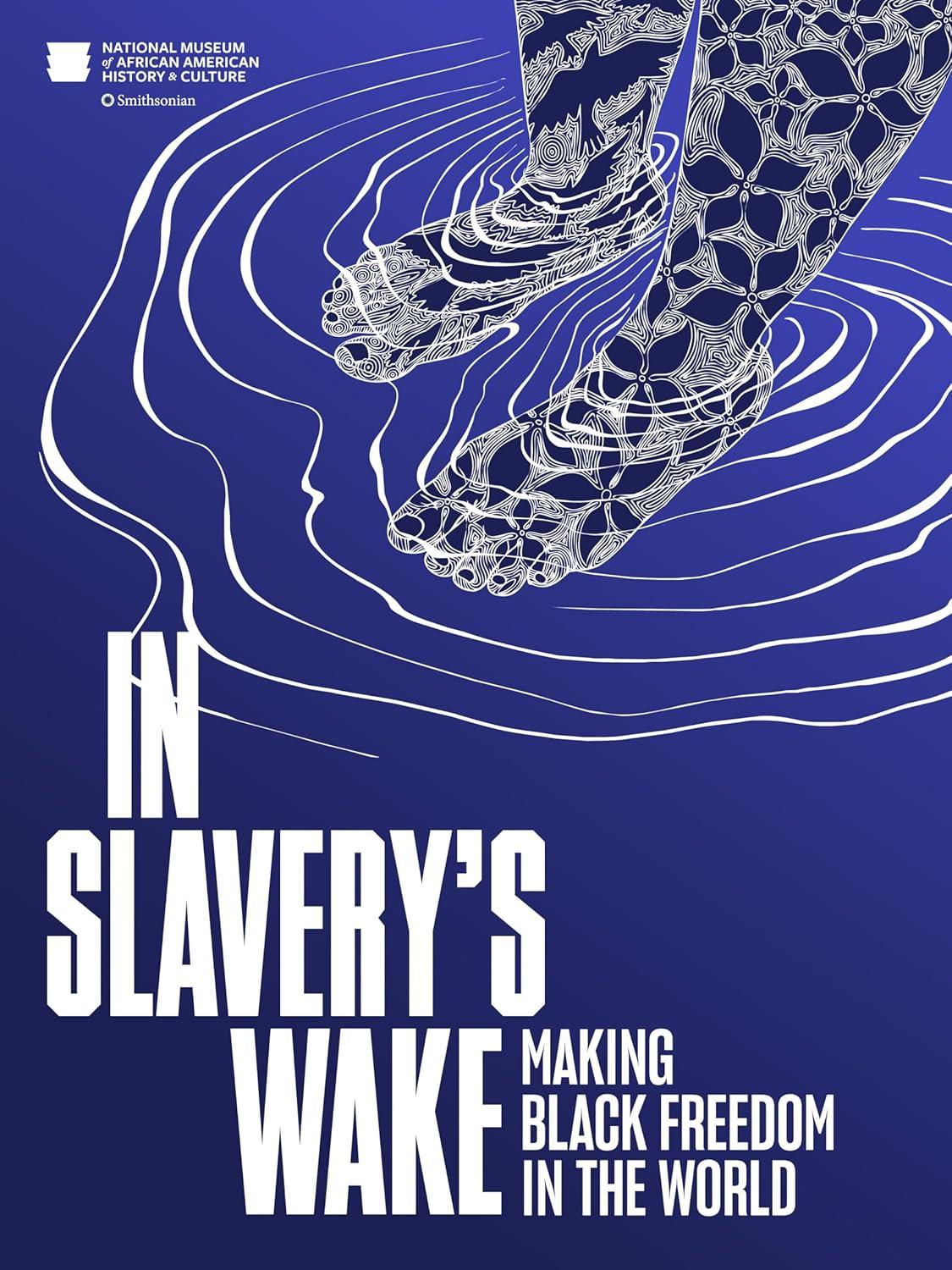

The story of how the capture and sale of human beings became embedded in the production of other merchandise is a terrible one. The story of how those human beings were made to work without end to enrich those who stole their labor is another terrible tale at the heart of our modern world. Slavery and the slave trade deserve to be mourned. The stories deserve our grief. They deserve a wake. They also must be understood as the source of current disparities in financial standing, incarceration rates, health, and life expectancy.

The damages that are at the heart of our modern world exceed those that I’ve charted here, of course, but my presumption is that the only way to understand today’s realities is to understand the history of race and racism that began with the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. The historian Walter Johnson writes that if you don’t start with the history of slavery, many of our contemporary problems simply don’t make sense. Thinking about history by starting with slavery does not congratulate those of us who are looking back on that history for how well we’ve done, how far we’ve come, how hard we’ve tried. Indeed, it’s a pretty sad place, and it means starting with a methodology that is steeped in melancholy. A melancholy born in the realization that human suffering has always been at the heart of economic growth.