Little more than a century ago, deep in America’s rural South, a community-based movement ignited by two unexpected collaborators quietly grew to become so transformative, its influence shaped the educational and economic future of an entire generation of African American families.

Between 1917 and 1932, nearly 5,000 rural schoolhouses, modest one-, two-, and three-teacher buildings known as Rosenwald Schools, came to exclusively serve more than 700,000 black children over four decades. It was through the shared ideals and a partnership between Booker T. Washington, an educator, intellectual and prominent African American thought leader, and Julius Rosenwald, a German-Jewish immigrant who accumulated his wealth as head of the behemoth retailer, Sears, Roebuck & Company, that Rosenwald Schools would come to comprise more than one in five Black schools operating throughout the South by 1928.

Only about 500 of these structures survive today, according to the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Some schools serve as community centers, others have restoration projects underway with the support of grants from National Trust for Historic Preservation while others are without champions and in advance stages of disrepair. Eroding alongside their dwindling numbers is their legacy of forming an American education revolution.

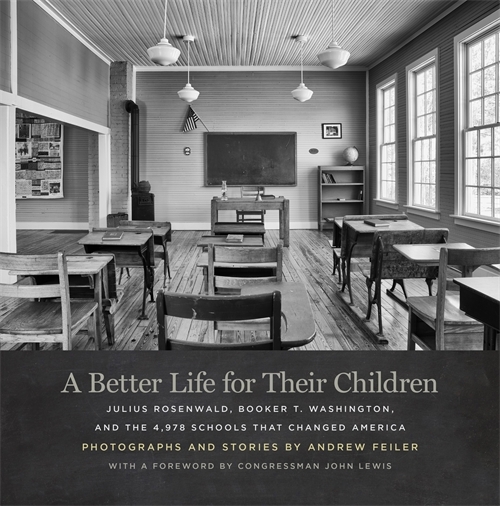

Photographer and author Andrew Feiler’s new book, A Better Life for Their Children, takes readers on a journey to 53 of these remaining Rosenwald schools. He pairs his own images of the schools as they look today with narratives from former students, teachers, and community members whose lives were molded by the program. A collection of photographs and stories from the book are also set to be featured in an exhibition at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, later this spring.

When Feiler, 59, first learned of Rosenwald Schools in 2015, it was a revelation that launched a nearly four-year journey over 25,000 miles throughout the southeast where he visited 105 schools.

“I'm a fifth-generation Jewish Georgian and a progressive activist my entire life. The story’s pillars: Jewish, southern, progressive activists, are the pillars of my life. How could I have never heard of it?” says Feiler, who saw an opportunity for a new project, to document the schools with his camera.

That the schools’ history is not more widely known is in large part due to the program’s benefactor. Rosenwald was a humble philanthropist who avoided publicity surrounding his efforts; very few of the schools built under the program bear his name. His beliefs about the philanthropic distribution of wealth in one’s own lifetime contributed to the anonymity, as his estate dictated that all funds supporting the schools were to be distributed within 25 years of his death. Many of the former students Feiler met with were unaware of the scope of the program, or that other Rosenwald Schools existed outside of their county, until restoration efforts gained national attention.