As for cabins themselves, they were generally seen as “rude” and “miserable,” and no self-respecting American would deign to live in one. Not permanently, at least. Cabins back then were temporary stepping stones meant to be abandoned once something better could be afforded; barring that good fortune, they were to be covered with clapboard and added to as the cornerstone for a finer home.

LOG CABIN PRIDE

But the log cabin and its inhabitants’ public image got a makeover after the War of 1812. The nation had just defeated the British for a second time, and Americans were feeling good, forging their own identity and distinguishing themselves from the old world. Log cabins—ubiquitous and appropriately rustic—started taking on an all-American sheen.

Soon enough, writers and artists were portraying them in a positive light. One notable example is James Fenimore Cooper’s 1823 novel The Pioneers, where the house of protagonist Natty Bumppo is described as being “a rough cabin of logs.” That scene in turn is thought to have inspired artist Thomas Cole’s 1826 painting, Daniel Boone Sitting at the Door of His Cabin on the Great Osage Lake. Together, these works helped spark an entire movement that saw the pioneer as a hero. Log cabin dwellers were no longer disdained for their rough edges; these same edges were what made them romantic and distinctly American.

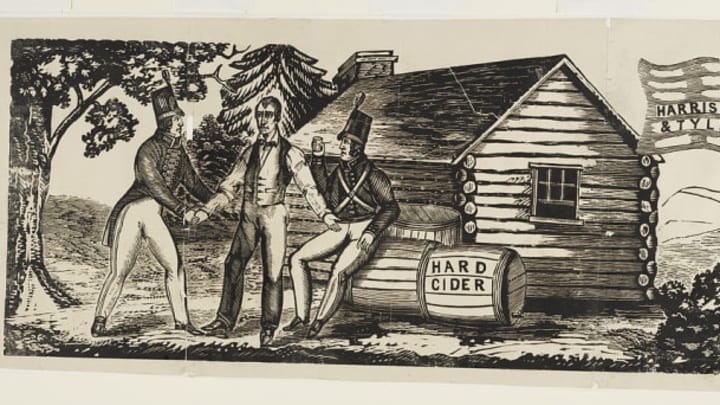

A "Harrison & Tyler" woodcut used in the 1840 campaign [Library of Congress]

Similar shifts occurred in the political realm during the 1840 election. President Martin van Buren faced an uphill battle for reelection that year, and a politically aligned newspaper thought it could give him a leg up by launching a classist attack against rival William Henry Harrison: “Give [Harrison] a barrel of Hard Cider, and settle a pension of $2000 a year on him, and my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his Log Cabin.” In other words: Harrison was an ignorant hick.

It was a lie—the wealthy Harrison actually lived in a mansion—but most of the public didn’t know it, and his rivals assumed voters would scorn Harrison’s poverty. They were wrong: Millions of Americans still lived in log cabins, struggling day-in-and-day-out, and they were not impressed. (“No sneer could have been more galling,” John McMaster wrote in his 1883 A History of the People of the United States from the Revolution to the Civil War.)

In no time at all, Americans rich and poor were displaying their Harrison love and log cabin pride by holding cabin raisings and patronizing specially-constructed log cabin bars, marching in massive parades with log cabins pulled by teams of horses, and purchasing heaps of Harrison-themed, log cabin-stamped merchandise, including tea sets, hair brushes, and hope chests. With his eye on the prize, Harrison gamely played into this fib, telling frenzied crowds that he’d rather relax in his log cabin than run for president, but that he had heeded their call to run for the White House. That fall, he won handily.