The Fair Housing Act—which Congress passed 50 years ago today, on April 11, 1968—had an impact on sellers and renters that was quickly felt. Progress was slow, but progress was visible. It has taken much longer, however, to uproot redlining and other practices by which banks routinized racial discrimination.

Fifty years after the Fair Housing Act, the full historical weight of banks’ discriminatory practices is still evident in the persistent racial segregation of communities. While discrimination in lending is illegal, disparities in lending are enormous. According to an investigation by Reveal from the Center for Investigative Reporting earlier this year, African Americans and Latinos continue to be denied mortgages at far higher rates than whites in 61 metro areas. Using the data from Reveal and other sources, CityLab has visualized how that discrimination manifests itself in two of those cities.

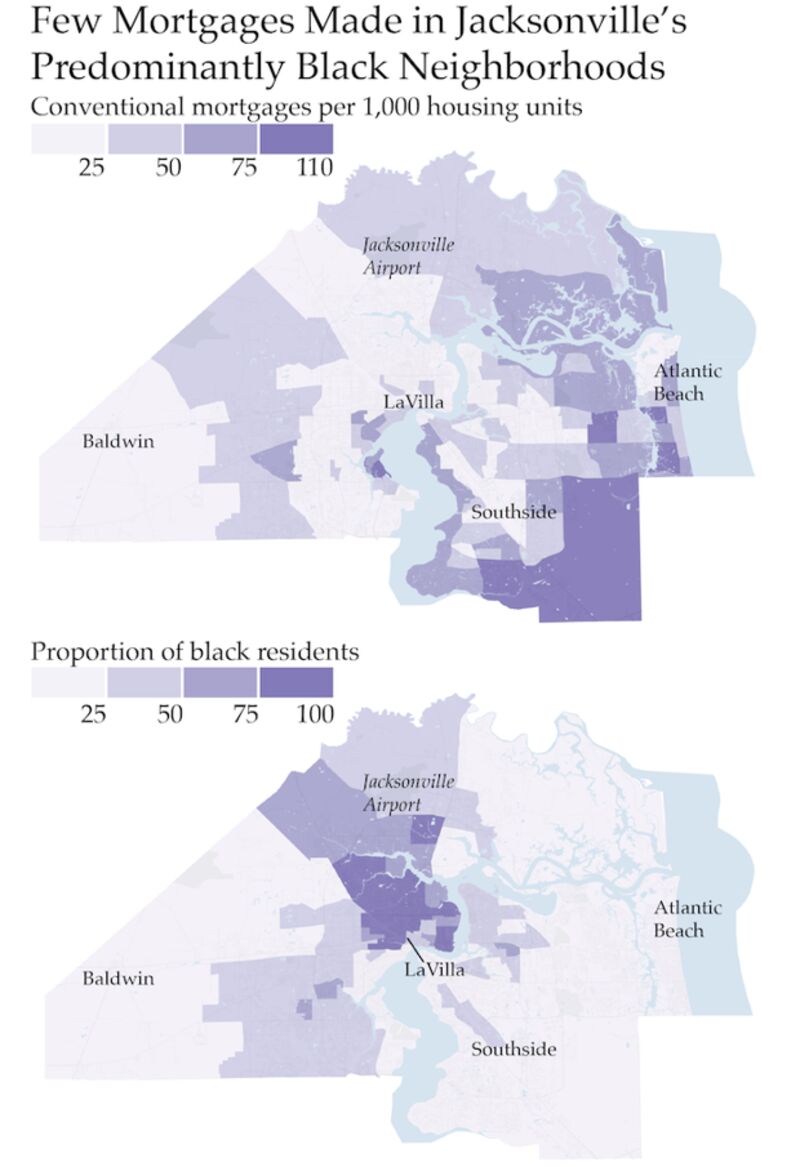

Mapping where banks approve or reject mortgages reveals a stark and dramatic pattern of disparity: Where de jure segregation was once the rule, de facto segregation still persists. For example, in Jacksonville, new home mortgages still fall within the very same lines that banks drew to prevent black families from moving into white neighborhoods or building wealth some 80 years ago.

The gulf between black and white households in new home mortgages reflects a vicious cycle—one in which a lack of wealth blocks the creation of new wealth, a cycle spanning generations.

In the early 20th century, LaVilla and Sugar Hill were upscale black neighborhoods in Jacksonville visited by the likes of Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Zora Neale Hurston. The area included a 30-acre park and stately homes for members of Jacksonville’s black professional class. Nevertheless, in the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) deemed LaVilla and Sugar Hill—along with other predominantly black neighborhoods—as hazardous or in decline. So-called hazardous areas “embrace[d] principally the Negro areas of the city” including “a community of the best class of Negros,” as HOLC described them at the time.

The red areas delineated places where traditional lenders would not make loans. Today, these formerly redlined areas in and around downtown remain where the majority of the Jacksonville’s black residents live. They are also places where the lowest number of the conventional mortgages are made in the city.

Predominantly black census tracts in Jacksonville—where more than three-quarters of the population is black—were granted four conventional mortgages per 1,000 housing units in 2015 and 2016. The rest of Jacksonville had nine times as many mortgages in the same time period.