On a Saturday morning in the summer of 1994, first lady Hillary Clinton was unnerved as she stood at a lectern in downtown Seattle. Hundreds of demonstrators had infiltrated the crowd at an outdoor rally for a White House plan to redesign the nation’s health-care system, their messages ugly and personal.

The first lady faced signs saying “Heil Hillary,” and she could barely hear her own voice over the boos. Sensing trouble, her Secret Service detail had, for the first time that day, persuaded Clinton to wear, under her crimson jacket, a bulletproof vest.

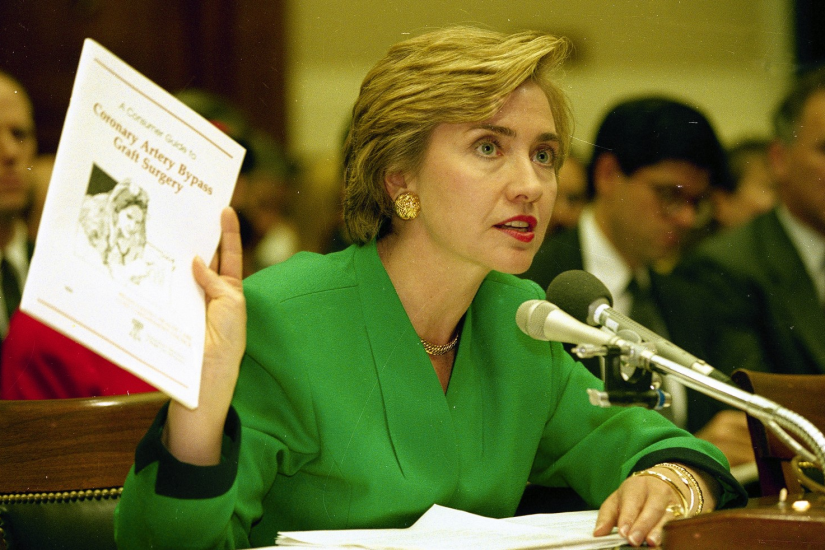

The charged feelings about Clinton and health-care reform that had spread across the country were part of a spectacular downfall from a hopeful beginning 19 months earlier, when she and her husband, President Bill Clinton, moved into the White House determined to bring health insurance to every American. She seized an unprecedented role for a first lady, taking charge of a main policy initiative. Two months after the Seattle protests, the Clintons’ quest to reform health care was dead, having failed even to get a floor vote in either chamber of Congress.

From the ashes of this defeat emerged a chastened Hillary Clinton whose caution has, over the years and as she seeks to become the nation’s first female president, become a hallmark of her identity.

The 21 months from the dawn to the demise of the Clinton health plan showed the first lady as the Washington neophyte that she was, overvaluing her own ideas, misreading power relationships, crusading for a complex plan that would have disrupted many Americans’ health care. She has not attempted anything as daring again.