Thirty years ago, Schindler’s List, directed by the illustrious Steven Spielberg, debuted in theaters across the United States. It not only was the most consequential English-language movie about the Holocaust up to that point but also shaped filmmaking and public consciousness of the genocide for years to come.

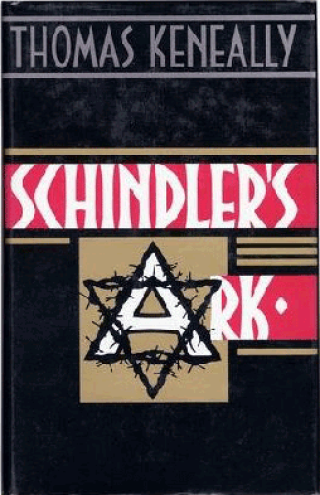

Schindler’s List is based on Schindler’s Ark, a 1982 novel by Australian author Thomas Keneally, who famously wrote the book after he tried to buy a briefcase in Beverly Hills, California, and had a chance encounter with Leopold Page, a Polish Holocaust survivor. Formerly known as Poldek Pfefferberg, Page told Keneally about the Nazi who saved him and his wife during World War II. The Nazi in question, Oskar Schindler, is credited with saving more than 1,000 Jews by putting them to work at his Krakow enamel factory, thus sparing them from deportation and death.

Schindler’s List tells the story of the eponymous German industrialist, who is played by Liam Neeson. It shows how the Nazis rounded up Jews in ghettos, then moved them to concentration camps, where they existed at the mercy of the SS—notably, in this case, Amon Göth (Ralph Fiennes), commandant of the Krakow-based Plaszow camp. Comparatively, Schindler’s Jews were lucky: He established a Plaszow subcamp on his factory’s premises, where, as survivors have recounted, they could rest if they were sick and weren’t arbitrarily shot. Toward the end of World War II, when the Nazis sent most camp inmates on death marches to hide them from the advancing Russians, Schindler transferred his workers to a new factory site in Brünnlitz, then part of occupied Czechoslovakia. He even secured the release of 300 women mistakenly sent to Auschwitz instead of Brünnlitz.

After meeting Page, Keneally decided to write a book—a novel, since he was a novelist—about Schindler’s story. “I didn’t want to give it up,” he says. “I was really hooked on this idea of highly imperfect deliverance.” (Schindler’s Ark spends more time on its protagonist’s backstory than the movie does, detailing how he used World War II to become rich.) Keneally was originally going to write the screenplay for the movie, but that job ultimately went to Steven Zaillian, whose more recent credits include Moneyball and The Irishman.