There was something undeniably hip, Savage contends, about homosexuality: It was cool, it was glamorous, and, to put it bluntly, it sold. It’s a counterintuitive argument because we tend to imagine the decades after World War II as years of the closet, as a time before the queer subculture had come into its own and before it enjoyed any purchase on mainstream culture. But long before Troye Sivan made a name for himself as an unabashedly gay singer—before the United States and Great Britain decriminalized sodomy and even before the first gay liberation movements of the 1970s—queer subcultures shaped the beat of popular music in the postwar world.

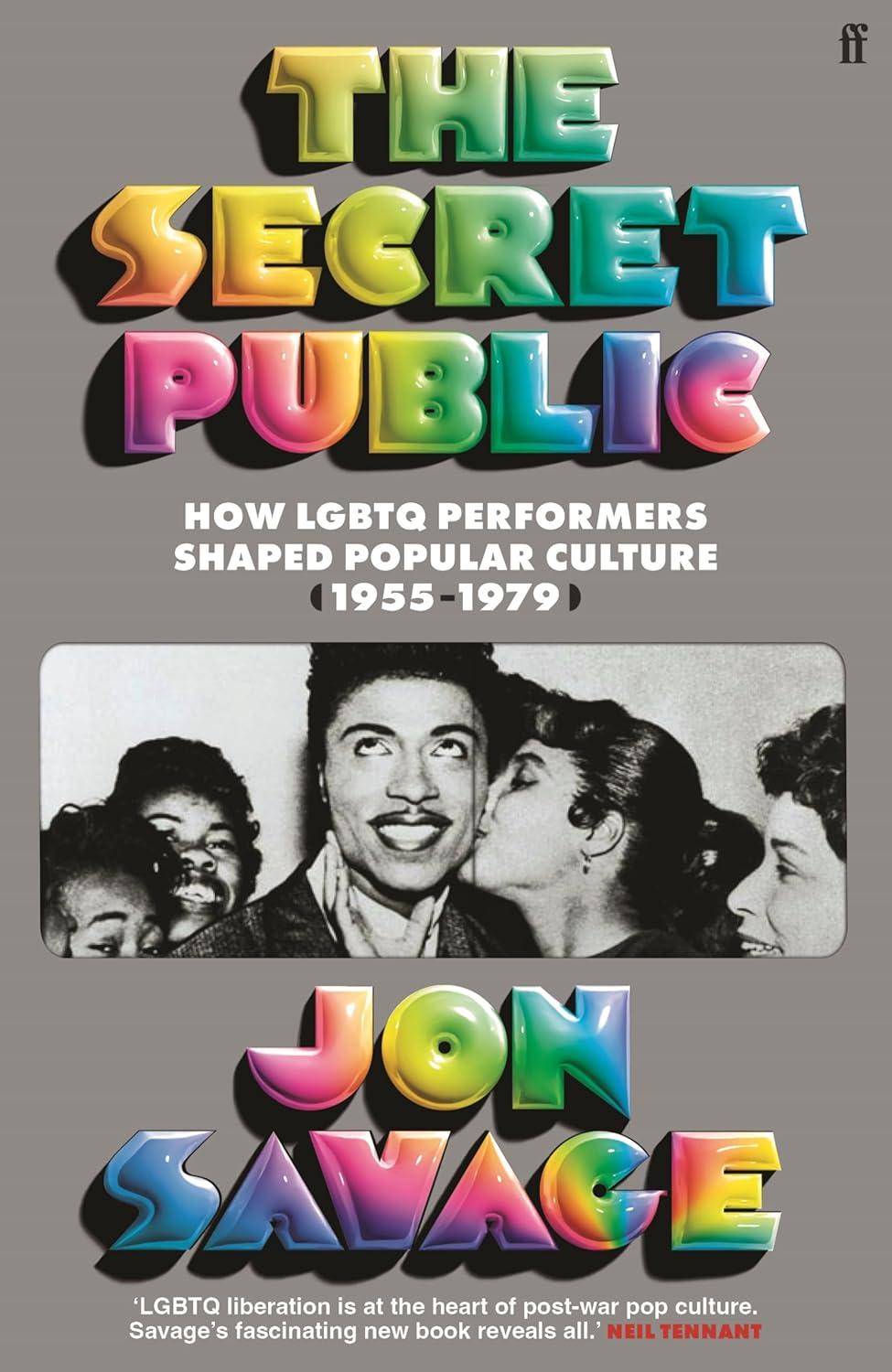

On December 5, 1932, Richard Penniman was born the third of 12 children in Macon, Georgia. A Black boy in a racist country, he grew up singing gospel in and out of church. In the evenings, he worked at the local bus station, where he would see “people come in and trying to catch something—you know, have sex.” As a teenager, he fled home—his father beat his “half a son” regularly—and started singing with traveling bands. Adopting the name “Little Richard,” he recorded his breakout hit “Tutti Frutti” in 1955. The song, which sold 200,000 copies in a month, was an early sign of how the gay subculture had begun to interpolate itself within modern music. Its “breakthrough sound of freedom, couched in extreme androgyny” appealed to growing hordes of teen fans eager to listen.

That teenage economy is the linchpin of Savage’s book. In the 1950s, the number of young people began to grow year after year, as did their purchasing power, the economic swell of the postwar baby boom. With employment high and wages competitive, marketers began to turn their attention to what British pollster Mark Abrams termed “the teenage consumer.” In 1958, Abrams estimated, there were some six million Britons aged 16 to 25, with around 900 million pounds per year to spend at their discretion. Whatever—or whoever—could capture their imaginations stood to make a fortune.

The desires of the young, then, were the motor that powered the fluctuations in fads and fashions across the postwar decades. A series of musical styles came and went, from the rock and roll of the Beatles to the glam rock of David Bowie to the disco of Gloria Gaynor. While not all of these singers were queer, they were, as Savage highlights again and again, often managed by gay men who understood that their records were spinning in the gay bars of London and New York.