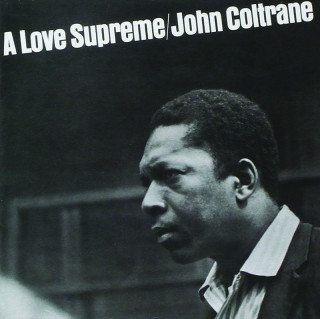

One of the most important artists in the 1960s, Coltrane passionately expressed his African American Islamic spirituality both in his album A Love Supreme (Impulse!, 1965) and in his exploration of self-purification, new musical forms, and the Black Arts movement in New York. Coltrane expanded the geographic and religious frame of black internationalism, experimented with new sounds and spiritual traditions from the Third World, played with Muslim artists in his band, and developed a serious interest in Sufi mysticism.

He incorporated Islamic themes and Middle Eastern and Indian modal forms into his music, used African polyrhythms and themes in his improvisation, and included what Yusef Lateef called “Islamic poetry” in his iconic album A Love Supreme. In this way, he brought together in jazz the liberation values and struggles of African Americans, Asians, and Africans in a “just universal order” whose cultural and racial diversity paralleled that of the global Muslim community—the ummah—itself.

The saxophonist pursued an improvisational Afro-Asian, African, and Islamic path to A Love Supreme during a period when Black Power activists like Malcolm X and Amiri Baraka demanded a reconstruction of black religious and musical identities drawing on Third World sources, to achieve their revolutionary political goals. Black Power activists admired Coltrane as one of their heavy spirits. By the 1960s, he came to believe that performance of jazz was “personal spiritual expression, and [that] the artist should be fully committed to… erasing aesthetic boundaries and proscriptions about style” to explore spirituality in music. The religious and artistic quest that led to the Islamic spiritual themes in his album was inspired by the musicians from the early 1960s who explored new forms of spiritual creativity and sources of sound and expression from India, West Africa, and the Middle East.

John Coltrane’s provocative musical and religious universalism intersected with his black Atlantic cool style, his sense of independence and liberation, and his transnational vision during an African American cultural revolution, and culminated with his interest in attending Malcolm X’s speeches in New York City, his musical and religious projects with Yusef Lateef and Babatunde Olatunji, and his African travel plans at the end of his life.

Trane’s revolutionary artistic and religious values helped to create alternative transnational notions of black masculinity in jazz. The transnational musical and religious impressions from Asia, Africa, and the Middle East that animated his new soundscape intersected with the global span of African American Islamic geography expressed in the construction of an Asiatic black masculinity in the Nation of Islam and other Muslim communities.