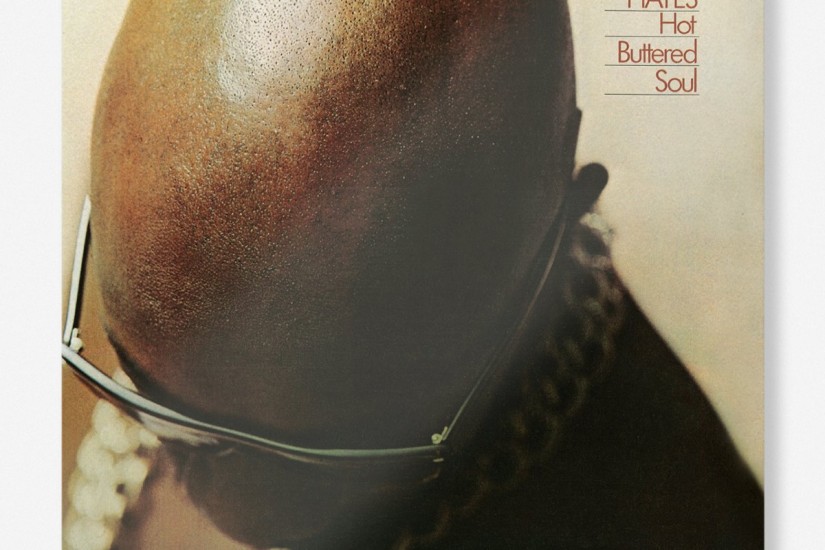

Fifty years ago last summer, he released one of the most extravagantly beautiful musical manifestos of the modern era, “Hot Buttered Soul.” The forty-five-minute album, consisting of just four extended psychedelic-orchestral tracks, changed not only the sound of soul but also its scale. Hayes, by presenting himself with all the bravado of other soul men, but at half the volume, traded the big-voiced charisma that had defined soul in the nineteen-sixties for a more conceptual, introspective approach. Fittingly, the cover of “Hot Buttered Soul” featured the dome of Hayes’s shaved, bowed head.

“Isaac was just cool as shit,” said the drummer Willie Hall, who worked with Hayes at Stax Records, in Memphis. “He would look up in the top of his head, the third eye, trying to come up with an idea—boom, it would come—perfect.” Hayes is seldom remembered as an enigmatic, restless creative, and even less so as a political leader. But he was, in some ways, a race man cut from conventional cloth. He had been born into desperate poverty, and moved around to various parts of Tennessee, where his family nearly froze in the winters and starved all year long, and the experience radicalized rather than defeated him: he helped to register black voters in the South, pushed for greater black representation at Stax, and co-founded a group called the Black Knights, to protest police brutality and housing discrimination in Memphis. On “Hot Buttered Soul,” he expressed his belief in black power in more experimental terms: through ostentatious claims to musical space.

The album was both a product of and a departure from Hayes’s earlier work at Stax, where he had honed his skills as a pianist—he filled in for Booker T. Jones while Jones was away at college—and where he proved to be an especially gifted songwriter. Along with David Porter, Hayes wrote some of the label’s most iconic hits, including Sam and Dave’s “Soul Man” and “Hold On, I’m Coming.” Hayes wanted his own star turn, but, as he later explained, the Stax co-founder Jim Stewart thought his voice was “too pretty.” “At that time we were living in a James Brown era,” Hayes noted. “Rough singing . . . [but] I was a soft singer.” Sales of his 1968 solo début, “Presenting Isaac Hayes,” were unimpressive.

But then Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed, in Memphis. Hayes, who had considered King a friend, “flipped,” as he put it, and became more “rebellious” and “militant.” For a time, he also went quiet. “I could not create properly,” he said. “I was so bitter and so angry. I thought, What can I do? Well, I can’t do a thing about it, so let me become successful and powerful enough where I can have a voice to make a difference. So I . . . started writing again.” Hayes released “Hot Buttered Soul” in the summer of 1969, as part of Stax’s “Soul Explosion,” a release of twenty-seven albums designed to help the company recover from a disastrous distribution deal with Atlantic and the death of the label’s star, Otis Redding. But Hayes’s ambitions were less commercial than creative: “I didn’t give a damn if ‘Hot Buttered Soul’ didn’t sell,” he said, “because there were twenty-six other LPs to carry the load. I just wanted to do something artistic, with total freedom.”